This year, 3,000 practitioners came to our annual Symposium to explore the fundamental question: are we any closer to unraveling the mysteries of psychotherapy than when Freud became the first therapist to complain about client “resistance”?

Have you wandered into the wrong hotel ballroom? You’re looking for the psychotherapy conference you registered for, but this dimly lit space with the jazz trio playing on stage and the moody stage lighting seems more like a hip, after-hours club than a place where you go to earn CE credits. Besides it’s only eight o’clock in the morning. What’s going on here?!

What’s going on is the annual Psychotherapy Networker Symposium. Over the 36 years of its existence, this Symposium has earned a reputation as the profession’s most spontaneous and stimulating gathering by combining inspiration and learning in ways unheard of in the normally straitlaced world of professional conferences. Its 125-member faculty connects bestselling authors, distinguished researchers, and stalwarts of the therapy workshop circuits with street drummers, artists, dancers, and professional entertainers. The last thing anyone expects of you here is to act like a stiff therapist tied to your appointment book. Instead, you can open up to whatever fun encounter, new idea, or exciting conversation comes your way. You can engage with dynamic speakers and kindred spirits, dance to Latin rhythms with your morning cup of coffee in hand, and spend four days roaming the halls of Washington, D.C.’s most elegant art deco hotel with the unbridled abandon of a high school student between classes.

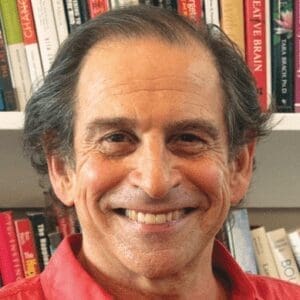

This year’s Symposium, The Therapist’s Craft: Healing Connection in a Digital World, brought together 3,000 mental health professionals for something increasingly rare these days—a no-holds-barred, face-to-face, nonvirtual experience celebrating the much-beleaguered profession of psychotherapy. The conference was organized as an exploration of therapy, not as an art or science, but as a craft. But what exactly does craft have to do with therapy? Before the gala musical opening performance in which he warned the audience he’d be unleashing his “inner Beyoncé,” longtime Networker Editor and Symposium MC Rich Simon offered his take on the Symposium theme.

Every year at Symposium time, we at the Networker find ourselves asking the same fundamental question: what is therapy, anyway? Is it an art or a science? Are we any closer to unraveling its mysteries than when Dr. Freud first moved that old chaise lounge from his attic to his office and, soon thereafter, became the first therapist ever to complain about his clients’ “resistance”?

Some would argue that we’ve come a long way since Freud. They believe that therapy is becoming an increasingly more rigorous scientific enterprise. Yet, as more and more metanalyses are done of widely varying clinical approaches, something disconcerting to lovers of scientific predictability keeps turning up. There is, it seems, surprisingly little difference between different therapy models in producing clinical success. So what is it that makes the difference? With all due credit to the therapeutic acumen of James Carville and his crew, here’s the bottom line: it’s the relationship, stupid!

We called this year’s meeting “The Therapist’s Craft” because we think that, despite the fancy credentials we like to use on our business cards, this Symposium is best thought of as a gathering of craftspeople. We’re not experts in knitting or pottery making, but in the highly interactive craft of healing conversation—the kind of conversation that, if repeated over and over, builds a relationship, which can itself lead to a subtle but real transformation in the lives of our clients.

A craft is basically the conscious, intentional pursuit of certain, often complex and difficult, skills and their practical application with a specific end in mind. In a sense, all artists and even scientists are craftspeople. They’ve spent years honing the kind of practical expertise without which most great visions—artistic or scientific—can’t be realized. It isn’t magic, nor is it simply a matter of learning a manualized procedure by rote. A craft requires both skill and awareness, both routine behaviors and imaginative power, both applied intelligence and the capacity for intuition.

This has all been brought home to me over the last couple of years through my own late-life experience of learning a new craft—or rather, learning an old craft better. I was always reasonably competent at basketball, even without any real coaching, although LeBron James definitely had nothing to fear from me. At this stage of my life, however, as my wife Jette will readily tell you, I probably shouldn’t be playing the game at all, out of respect for my aging joints and other increasingly imperfect body parts.

Nevertheless, a couple of years ago, I fell in love with the Dallas Mavericks during the NBA playoffs. In my new starry-eyed adoration of this team, I got to thinking that maybe even I could become a better basketball player. And, of course, I heard the underlying drumbeat of so many things in my life these days: if not now, when? So I submitted myself to a 26-year-old, wise-beyond-his-years coach named Andrew.

In our transference-rich relationship, Andrew became a mix of both my part-time son and part-time father figure. More than anything else, he showed me that playing basketball well was largely a matter of learning and practicing a constellation of highly specific skills that no one had ever taught me. I’d always had a solid, familiar way of playing, and my moves had a long pedigree, going back to P.S. 79 in the Bronx. However, in basketball—at least as Andrew taught it—it isn’t enough just to rely on the same old stuff. He expected me to practice new footwork and other skills that I’d never tried before. Far from depending on intuition or innate artistry, learning a skill actually depends on tolerating occasionally toxic levels of awkwardness and discomfort. It’s a matter of trying and failing, trying and failing, trying and—maybe by the 30th time—failing a little less badly.

For example, take the time that Andrew decided to teach me how to execute a tricky between-the-legs crossover dribble. The first times I tried it, I felt hideously un-Michael Jordan-like. But there was enough blind, stubborn will in me to make me grit my teeth and keep doing it, ignoring the persistent thought that I was a childish idiot to be doing any of this at all. So I practiced this move hour after hour, fumbling the ball, losing my dribble, finding new, even more comically grotesque ways to dribble it off my leg again and again, making mistake after mistake. And then, one day, I just got it!

The connection between this experience and therapy is obvious—right? Well, let me say it anyway. When you keep honing your craft, practicing new skills, and trying systematically and purposely to get better at what you do, you don’t just become more truly helpful to your clients. The better you get at doing something, the more you love it, the more inspiring and fascinating it seems to you. And, of course, the circle completes itself: the more joy and satisfaction you get from work, the better you’ll be at it, and the greater your desire will be to keep on improving.

But let’s face it: there are no shortcuts. Teaching and practicing a craft takes lots of time. So our theory-heavy professional training, from grad school on, hasn’t been focused on the actual nuts-and-bolts of the therapy craft. Today, we often approach the making of a therapist the way the Middle Ages approached the making of physicians: they were supposed to be well versed in the Theory of the Humors, but weren’t required to trouble themselves too much about the messy workings of the actual human body.

By now, it’s pretty clear that you can’t improve the way you do therapy just by reading about theory. Nor do you get better just by continuing to do what you’re doing in the hope that, somehow, just adding more years of “experience”—the same experience over and over—will automatically make you more clinically effective. To become a better craftsperson requires sustained, focused, deliberate, systematic effort, and often in precisely those areas you’re not so good at and find least enjoyable.

So who wants to do that? In a way, it’s like every exercise program you’ve ever started and failed. You know that doing those leg lifts and push-ups and crunches not only regularly, but correctly, will improve your strength and fitness, but how many of us can stand to keep it up? I suspect that the reason there’s such a huge amount of self-help literature out there is that so little of it actually gets used. People keep buying the books, reading them alone at home, trying to follow the advice, getting discouraged early on, then buying a new book, and then another, looking for the one that’ll help them make big, important changes in their lives effortlessly.

The default condition of most of us human beings is kind of lazy. We need the prospect of some reward, some new stimulation or energy, the mobilization that fresh inspiration brings to make significant gains in knowledge and skill. And the key to experiencing that is to feel a connection to something larger than yourself. To get there, there’s nothing like feeling yourself a member of a band of brothers and sisters who share a similar vision.

So there’s a reason for team sports after all, besides an excuse to drink beer in front of the TV. The thrill of competition and the fear of letting teammates down spur team members to display new feats of exertion and reach higher levels of performance. This communal reinforcement of what’s best in each one, more than anything else, keeps their practice more fully mindful and aware, rather than a matter of automatic routine. Team members have to keep learning, keep trying to get better, keep aspiring to be at the top of their game.

Whatever drew us into psychotherapy in the first place—a fascination with relationships and the process of human change, a desire to be genuinely helpful to people in pain, even the hope of making the world a little bit better—we’re sure not in it for the prestige or the power or the money. We need the energy, the excitement, the inspiration of our colleagues to help us renew our commitment and to encourage us in pursuing this incredibly demanding, often deeply discouraging, yet fascinating and deeply rewarding profession.

Photo © Jacob Love / Susan Osofsky

Rich Simon

Richard Simon, PhD, founded Psychotherapy Networker and served as the editor for more than 40 years. He received every major magazine industry honor, including the National Magazine Award. Rich passed away November 2020, and we honor his memory and contributions to the field every day.