It might feel intuitive to give your client a diagnosis when you spot the symptoms of a problem that’s causing them distress. After all, once the therapist and client are on the same page about the issue, they can get to work, right? Not necessarily. Sure, for some clients, a diagnosis provides clarity, giving shape to problems that may have long felt mysterious and made them feel alone. But when it comes to more stigmatized diagnoses, like borderline personality disorder (BPD), it can not only alarm clients, but provoke defensiveness, elicit shame, damage the therapeutic alliance, and even threaten to derail therapy altogether.

The notion that some clients may be blindsided or offended by a BPD diagnosis is understandable. Mental health professionals have called clients with BPD difficult, erratic, antisocial, delusional, and hostile. Media portrayals don’t help either. Characters like Alex Forrest, played by Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction, and Annie Wilkes, played by Kathy Bates in Misery, have BPD. While there’s much, much more to BPD and clients who suffer from it, I get it. From the client’s perspective, if you’re going to be stigmatized or rejected because of a label, why would you want it?

As clinicians, we don’t usually have a choice about whether or not to diagnose a patient: for insurance and bureaucratic reasons, it’s required. But we need to consider not only what diagnosis to give—in essence, how to diagnose on a case-by-case basis—but also the pain or hardship that can result. I learned this the hard way with a client whose BPD diagnosis put our relationship in jeopardy. But I also learned that, with work and humility, we can restore and strengthen the therapeutic alliance and then talk more deeply about the issues at hand.

A Diagnosis Emerges

Rhonda was referred to me by a colleague who saw her for medication management. She was in her mid-30s and wanted to start psychotherapy because she’d had a history of suicidal ideation and profound difficulty managing interpersonal relationships. These are hallmark symptoms of BPD, but neither my colleague nor I included the diagnosis on her record. My colleague had given a bipolar diagnosis because they share some diagnostic criteria. I’m admittedly less interested in diagnoses than in fostering a strong therapeutic alliance, so that’s where I directed my attention with Rhonda.

Rhonda had long experienced negative interactions with authority figures she’d turned to for help—including mental health professionals. Her trust was hard-earned, but it was my goal to build it. At times, our sessions felt like a chess match, where each move was made with the goal of inching Rhonda toward healthier thoughts and behaviors, but I welcomed the challenge and appreciated her tenacity. I admired her willingness to show up each week, despite how difficult the process was for her. I knew it would take a good deal of effort to break through the self-isolation behaviors that had protected Rhonda, but I was determined and hopeful we’d be successful if she stuck with it.

Several months into our work, Rhonda experienced an acute episode of suicidal ideation. She was highly distressed in our session and having difficulty regulating her thoughts and emotions. I asked her explicitly whether she intended to harm or kill herself. She said no. Because she’d never attempted suicide or harmed herself before, and denied having a suicide plan, I didn’t believe it was necessary to have her admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Plus, I knew it would do irreparable harm to our relationship. But her level of dysregulation rattled me. I asked if she’d be amenable to my calling her after work that day to check in on her. She said yes. When I spoke to her on the phone several hours later, she’d settled down. I asked her to identify a few friends she could contact. Given the seriousness of the episode, we discussed the need for her psychiatric nurse practitioner to adjust her medication. She promised to schedule an appointment with her the following week.

The storm had passed, but I leapt into action to help ensure Rhonda’s safety. My training had taught me that when someone’s life is in your hands, hubris is dangerous. It’s essential not to rely solely on your own judgment, but to get advice from other clinicians. I work with a talented group of therapists with decades of experience across multiple treatment modalities, so I sought their feedback during group supervision. One colleague opined that Rhonda might be suffering from BPD and encouraged me to consider additional interventions to treat it.

This gave me pause. I thought of my past experiences working with patients with BPD and began to think about their relationship with those three words—borderline personality disorder—and what it meant for their treatment.

The Double-Edged Diagnosis

The first client who came to mind was the first person I’d ever treated who suffered from BPD. She’d been in her mid-20s at the time, and her interpersonal relationships had been highly turbulent. Early in our work, she’d told me her mother had suffered from BPD, and in what felt both preemptive and defensive, she’d declared that she did not. In subsequent years when she experienced periods of high distress and heightened feelings of victimization, she reiterated, unprompted, “I am not borderline!”

I’d never retreated from confronting her maladaptive interpersonal patterns. I’d suggested interventions like dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), proven effective for people who suffer with BPD, but I respected the boundary she’d set, believing that giving her a label she found so threatening would do more damage than good.

I’d been working with another young woman in her mid-20s when a chaotic romantic relationship suddenly led to suicidal thoughts and violent outbursts she’d never revealed before, including banging her head repeatedly against her bed’s headboard in moments of distress. Based on this new information, a BPD diagnosis was irrefutable. Given her intellectual curiosity and budding interest in psychology, I sensed it would be helpful to share it with her. My intuition paid off.

She felt comforted to learn that what she’d been experiencing had a name, and less alone knowing other people shared her condition. Within a few months of the diagnosis, she’d started a medication regimen and was participating in a DBT group. She immersed herself in the literature to better understand BPD, and her explosive, violent episodes vanished.

The Fumble

As I processed my past experiences, trying to understand how they could inform my work with Rhonda, she met with my colleague—her psychiatric nurse practitioner—who caught me up on their session. Rhonda had agreed to change her medication, she told me, and she was confident that the new regimen would be effective. Before we ended our call, she mentioned she’d added a BPD diagnosis to Rhonda’s client record.

It seemed we’d taken the right steps to keep her safe. I was convinced of it when I saw Rhonda a few days later. She seemed calm and regulated, and I felt relieved.

Then, Saturday morning came.

Our practice’s online portal automatically charges clients’ credit cards at midnight following a session. In the morning, I send clients their bills for insurance reimbursement, which I did the day following my session with Rhonda.

A few hours later, I received an email from her: “I was filling out my insurance paperwork for this week and noticed a second diagnosis code on my bill. I’m wondering if this is something we need to talk about.”

My stomach churned. I should’ve advised my colleague to wait to revise the record until I’d had a chance to discuss the change with Rhonda. “We can definitely talk about this when I see you on Friday,” I wrote back. Then I steeled myself for what I knew would be a difficult next session.

The Recovery

It was time to use all the training I had as a therapist. If there was any way to recover from my mistake and save our therapeutic alliance, I had to handle this interaction with authenticity, contrition, and humility.

When Rhonda entered my office, her face was expressionless. Her eyes and mouth were held firm, like a soldier standing at attention, but her words revealed just how much effort her stoicism had required.

“I didn’t appreciate learning I have another disorder by looking at my invoice,” she said, folding her arms across her chest and clenching her fists.

She was furious not only about how she’d learned of the new diagnosis, but at my response to her email.

“I emailed you and asked if we needed to talk about this, and you totally dismissed me,” she said, her voice flat and listless. “I spent the entire week Googling what borderline personality disorder is, and everything I read just made me feel worse.”

I could tell that for Rhonda, being diagnosed with a personality disorder felt like a life sentence.

“If the problem is my personality, then there’s nothing I can do about it,” she said. “I feel like damaged goods.”

I had to face the fact that I, the person she should turn to for comfort and support, was responsible for making her feel this way.

As I advise my clients to do when they experience moments of stress, I took slow, deep breaths to calm myself. I treated myself with kindness and compassion. I reminded myself that although I’d made a mistake that had caused Rhonda pain and discomfort, it hadn’t been my intention. I cared about her and wanted a chance to rebuild the trust I’d damaged. I made space for her emotions. I fully accepted the blame. Full stop. No buts.

When I sensed she’d run out of steam, I said, “I both hear and appreciate how upsetting it was for you to see that diagnosis on your bill. You have every right to be angry with me. I should’ve spoken to you about it first. It was my mistake, and I’m very sorry. I understand how receiving a BPD diagnosis feels to you. I’d like to give my perspective, but only with your permission. Would that be okay?” Rhonda nodded.

“I’m not the kind of therapist who focuses too much on diagnosis,” I continued. “Yes, a new number was added to your record, but I don’t view you any differently than I did before. The single most important thing to me is keeping you safe. We got to the place we are now because you were experiencing an acute episode of suicidal ideation. I’ve been worried about you, and I hate to see you suffer so deeply. The responsibility I feel to ensure your safety and help you feel better is more important to me than any numbers on a bill.”

I noticed a softening in Rhonda’s jaw, and the tension in her eyes seemed to ease, so I continued. I wanted to offer something to address what she saw as the permanence of the diagnosis.

“I hear that this diagnosis feels intractable to you, but current neuroscience research shows we have the power to shape our personalities deliberately.”

In our typical chess match-style sessions, psychoeducation and sharing relevant research had been effective, but I realized there was nothing typical about this session. Rhonda’s eyes began to narrow again, so I quickly pivoted.

“Maybe now’s not the time to talk about research. Here’s the truth, Rhonda. I made a mistake. I let you down. I wish I could take it back, but I can’t. All I can do is ask you to give me another chance.”

She listened. Her anger, while certainly at a slow boil, was no longer bubbling over. Then, she made two meaningful confessions. She told me that while reading about BPD online, she’d recognized some of herself in the descriptions—which, she added, contributed to her anger.

Then, she said something even more profound.

“Once I saw all that stuff they said about how no one wants to work with people who are borderline, I figured you’d abandon me.”

This brave admission gave me the chance to assure her I was committed to her and our work together.

“I’m not going anywhere, Rhonda. You have my word.”

She must’ve believed me, because she’s shown up to every one of our sessions since. I’m grateful for that. Fortunately, her ability to stay in therapy has allowed us to explore what a BPD diagnosis means to her. She still sees herself in the thought patterns and behaviors associated with the diagnosis. She continues to read about BPD, and has since found more complete and compassionate depictions of people who suffer with it, which she’s found comforting.

I’ve wondered how the conversation may have gone if I’d spoken to her about the diagnosis before she’d discovered it on her bill. I’m not sure if she’d have been less angry. What I do know is that my misstep gave her the opportunity to feel angry and express that anger to someone who could tolerate it, own their mistake, and apologize for hurting her. It allowed her the chance to accept my apology and choose to maintain our relationship, even though I’d let her down. In fact, in the weeks that followed, she opened up about traumatic events she hadn’t revealed before. What could’ve led to a regrettable outcome turned out to be a happy mistake.

How do I decide whether it’s in a client’s best interest to introduce a BPD diagnosis over a diagnosis they might find less threatening? It’s complicated. Despite the prescriptiveness of the DSM, I believe diagnosing is more an art than a science. More importantly, clinicians have a responsibility to consider the individual and the potential impact a diagnosis like BPD may have on them.

A BPD diagnosis was anathema for one client. Uttering those words threatened to end the therapeutic alliance forever. For another client, it was a boon to our work. It made her feel less alone and more understood—essential ingredients in good psychotherapy.

As for Rhonda, I’ll never know how the diagnosis would’ve affected her if I’d properly communicated it, but this is clear: she was capable of so much more than the DSM’s diagnostic criteria suggest, and perhaps more than mental health professionals expect, based on the negative depictions of people who suffer with BPD.

The women whose stories I’ve shared, though they may share a handful of behavioral patterns, are different. To be effective clinicians, we need to treat our clients as more than their diagnoses: we need to treat them as individuals. This, I believe, is the best way to help alleviate their suffering and help them learn to navigate a world that often feels unsafe. For that, I don’t need the DSM: I need my humanity and compassion.

Case Commentary

By Anita Mandley

Jill Sammak’s case study shines a light on a tightrope every clinician must walk at some point because, as she rightfully points out, some clients find diagnoses helpful, while others bristle at them. And sometimes, with clients like Rhonda, it’s difficult to know how they’ll react. What we do know in this case is how Rhonda reacted after she learned about her diagnosis: she felt like “damaged goods,” as if BPD had mapped the trajectory of the rest of her life. The unusual way that she happened upon this diagnosis also highlights another truth about our work: that even experienced clinicians make mistakes. And, as in much of life, what’s most important is not the mistake itself, but how we manage it.

That’s why I was so impressed with Sammak’s process of repair. I don’t think it’s possible to totally avoid ruptures in relationships, which are like pieces of fabric. To keep the fabric intact, any tears have to be stitched up. And when the repair is done skillfully, the place where the fabric ripped can become stronger than it was before.

In therapy, not only does the immediate relationship become stronger after a repair, but the experience of repair is also healing. It serves to heal the wounds of all the times when there was no repair in relationships. Sammak’s process of doing this begins with humility. She admits she made a mistake and then takes full responsibility for it. She doesn’t get defensive or dismiss Rhonda’s reaction to the BPD diagnosis. Instead, she makes it clear how much she values their relationship and recognizes the need for repair. Then, seeing the activation shift in Rhonda’s body, she begins to give Rhonda hope that the diagnosis isn’t a life sentence.

We can’t overestimate the power of this process, which begins with our own self-awareness, moves to managing our own activation and fears with self-regulation, and then continues with humility, acknowledgement, and then the apology.

Of course, hindsight is 20/20, but in Sammak’s position, I would’ve met in advance with the psychiatric nurse practitioner who added the BPD diagnosis to Rhonda’s client record so we could’ve talked about our process together. I would’ve asked her to talk to me about making any changes to client records before submitting it to insurance, and I would’ve asked her to give me a chance to speak with clients about those changes before they saw it on a bill.

I also wondered whether it would’ve been possible to disagree with the psychiatric nurse practitioner’s diagnosis—and not adopt it myself—if I’d had a different conceptual framework. In fact, I usually diagnose clients who have a similar clinical presentation to Rhonda with PTSD or complex PTSD with disorganized attachment patterns. Sometimes I share details about cases with other providers who’d be likelier to diagnose clients with a personality disorder. In these situations, our dialogue is grounded in the spirit of humility, curiosity, and collaboration.

All in all, I believe Sammak’s skill and experience were invaluable in navigating the rupture and repair process and in helping Rhonda more fully accept herself and the challenges ahead of her. As Sammak writes, “We need to treat our clients as more than their diagnoses.” This is the key to opening them up to the possibility of healing.

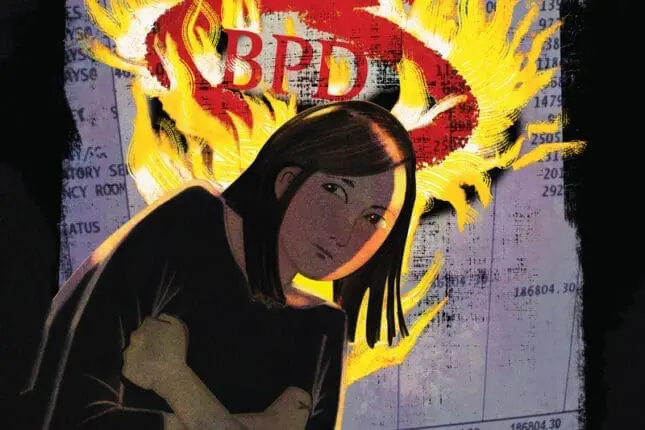

ILLUSTRATION BY SALLY WERN COMPORT

Jill Sammak

Jill Sammak, LCSW, CPC, ACC, has been a practicing psychotherapist in Manhattan for ten years. She has 25 years of business experience from Fortune 500 firms to nonprofits to start-ups, and she’s a leadership and career coach and the founder of Jill Sammak Coaching and Consulting, LLC. For more information, visit jillsammak.com.

Anita Mandley

Anita Mandley, MS, LCPC, practices at the Center for Contextual Change, where she focuses on clients who’ve experienced trauma. She’s the creator of Integrative Trauma Recovery, a group therapy process for adults with complex PTSD.