Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

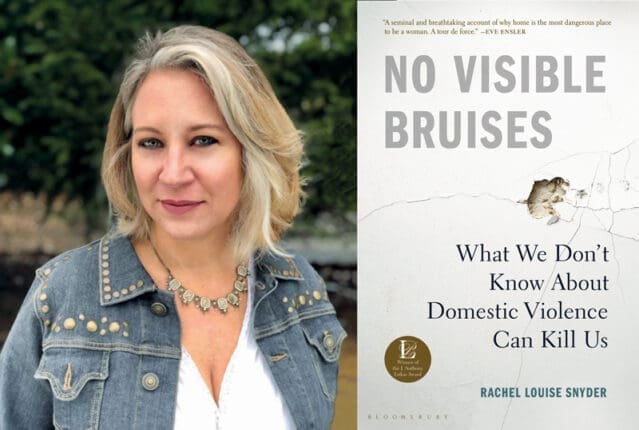

No Visible Bruises: What We Don’t Know about Domestic Violence Can Kill Us

by Rachel Louise Snyder

Bloomsbury

307 pages

978-1635570977

“Man kills wife, kids, and self.” Unfortunately, such gruesome headlines have become familiar in our culture. Yet even to people closest to the victims, the why and how behind this most brutal form of domestic violence nag uncomfortably with guilt-ridden questions about missed clues and unheard cries for help. But as journalist Rachel Louise Snyder points out in her unflinching exploration, No Visible Bruises: What We Don’t Know about Domestic Violence Can Kill Us, such crimes don’t lack clues so much as their seeming invisibility can make us all seem clueless.

That’s why Snyder takes great pains to pick apart the vicious cycle of silence that so often pervades and shields intimate partner violence from detection. Her extensive case histories and conversations with experts reveal a pattern of silence shared by victims, perpetrators, and even unsuspecting (or willfully blind) outsiders. First, victims learn to conceal their traumas out of a double-barreled sense of shame and realistic fears that divulging the truth or pressing charges might provoke their partners to further violence. Meanwhile, if or when confronted, perpetrators deny the seriousness of their actions as they minimize (“it was only a slap; she wasn’t hurt”), rationalize (“I didn’t stab her; she fell on the knife”), or rely on a still mostly male police force to “understand” their point of view. That is, if the police are even called. Because involvement by “outsiders” is a typical trigger for more or even worse violence, victims will often refuse to bring charges or decide to recant because they believe they have no other recourse but to remain in place, and in silence.

Finally, perpetrators further hedge their bets against detection by distancing or cutting off friends, family members, or others who might spot or intuit that something is amiss. And so the violence continues and, frequently, escalates, too often culminating in a murder–suicide scenario. In other words, if the clues seem invisible, that is by design. But, says Snyder, you can nonetheless learn to detect them, and in doing so might just avert a disaster waiting to happen.

Having spent the last decade taking a deep dive into the forensics and dynamics of intimate partner violence, Snyder has set herself the mission of revealing those clues for all to see and heed. She’s called attention to the numerous tools, strategies, and programs that aim to aid victims, rehabilitate perpetrators, sensitize police to the issue, and promote effective social services and counseling for all who are affected. Her range is impressive, her passion to educate more so, even if some aspects or types of abuse do seem shunted aside as a result of her focus on the most heinous examples of domestic violence: the murder of a spouse, and sometimes an entire family.

Snyder’s first lesson derives from the data. Last year, a United Nations study found that approximately 50,000 women were murdered worldwide by an intimate partner or family member. That translates into a rate of 1.6 women per 100,000 in the Americas. (By comparison, the rates are 3.1 in Africa, 1.3 in Oceania, 0.9 in Asia, and 0.7 in Europe.) A 2017 report by advocacy group Everytown Gun Safety found that 54 percent of American mass shootings included—and often began with—the murder of an intimate partner or family member. Still, those cases account for only a fraction of all occurrences of intimate partner violence. “Twenty people in the United States are assaulted every minute by their partners,” she writes.

From numbers, she turns to the case history of Michelle Monson Mosure, her husband Rocky, and their two young children, Kristy and Kyle. As it unfolds from the memories of the grandparents, siblings, and friends, the saga of this working-class family from Billings, Montana, both anchors and haunts the book. Only in retrospect do patterns of behavior emerge as a checklist of danger signs no one had thought to pay attention to or act on.

Michelle was just 14 when she met Rocky, her senior by a decade, who promised to protect her and seemed to be someone to look up to. At 15, she gave birth to their first child, and at 16 their second. Although money was tight for the young family, Rocky was infuriated by the notion of her working outside the home, and began exerting ever greater control over her. “He wouldn’t let her wear makeup,” Snyder writes. “He didn’t allow her to have friends over,” and he stalked her if she went somewhere without him.

Over their eight years together, he became increasingly controlling, demanding, and paranoid. But what could she do? Where could she go? Without a job, she had no money, and with Rocky severely limiting her contact with family or friends, she hardly had a social network to turn to for support. Only well into the escalating pattern did she begin to confide to a friend that his behavior was growing ominous. In addition to beating her in front of the kids, he’d begun using the kids themselves as pawns, acting out threats to kidnap or harm them if she didn’t do what he insisted.

Then, in September 2001, Michelle confronted him about an affair he’d begun, and his violence spiraled out of control. The police charged him with domestic violence, but they bungled the arrest and let him go almost immediately. Once free, he lost no time violating the protection order—at which point, in despair and with no means to support herself or her kids, Michelle felt she had no viable choice but to recant, go home, and try to placate him. In October, he killed them all.

Snyder teases out from this story observable patterns of silence and isolation, addressing the most commonly asked question about domestic abuse: if she was so scared, why didn’t she just leave? Her pointed answer: “to stay alive.” She likens violent perpetrators like Rocky to a raging bear on the attack, but a familiar one. Over the years, victims try various strategies to calm the bear, including “pleading, begging, cajoling, promising, and public displays of solidarity, including against the very people—police, advocates, judges, lawyers, family—who might be the only ways capable of saving their lives.” When those strategies fail, which they almost always do, since housing for victims (especially those with children) is extremely limited, leaving often means homelessness, as suggested by the statistic that more than half of all homeless women were victims of domestic violence.

Nonetheless, the very question presupposes that it’s the victim who must leave. As one domestic violence advocate told Snyder, “We don’t say to bank presidents after a bank’s been robbed, ‘You need to move this bank.’” Rather than asking why victims stay, Snyder believes the better question is: how do we protect them?

Developing and disseminating tools for prevention and awareness are among the first steps. In 1985, Johns Hopkins professor and researcher Jacquelyn Campbell introduced the Danger Assessment questionnaire and timeline to help abuse victims assess their danger of being murdered. It weighs 22 risk factors, ranging from isolation to threats of violence to extreme jealousy to gun ownership. The accompanying timeline charts the occurrence of past incidents of violence, documenting a trajectory that can alert victims to the seriousness of the situation.

An attempt at strangulation, Campbell found, was the most significant indicator of imminent homicide. A pattern of continually escalating violence is an equally dangerous signal that the next escalation could prove fatal. Having a tangible knowledge of these warning signs allows victims to recognize their level of danger and motivate them to make a safety plan.

Because victims and their advocates need to better communicate, share information, and coordinate efforts with police and law officials, Campbell also put together a Lethality Assessment Program to train and sensitize police when they answer domestic abuse calls. These and similar tools are now being used throughout the world. One of the most promising programs to emerge from this work is in Cleveland, where a Homicide Reduction Unit task force assigns detectives to regularly visit, check in on, and offer help to women whose scores show they’re at the highest risk for becoming victims of homicide.

Snyder also reports on intervention programs that try to get perpetrators to take responsibility for their harmful behaviors and change their mindset. More than 1,500 of these programs exist worldwide, some in prisons, others on the outside, mandated by courts as conditions of probation or parole. These are not to be confused with anger-management programs, which have not been shown to be effective in reducing domestic violence, because most batterers don’t have high levels of anger. Instead, Snyder says, these psychoeducational, group therapy programs “help an abuser recognize destructive patterns, understand the harm they cause, develop empathy for their partners, and offer them an education in emotional intelligence.” Some research suggests they can reduce domestic violence recidivism, but more evidence is needed to show why and how some programs are more effective than others.

Undoubtedly, Snyder’s work is valuable in bringing the dangers of domestic violence to public attention. Still, she omits aspects that deserve attention, such as domestic violence in same-sex partnerships and when it’s perpetrated by women on men. Her discussions of societal and cultural views of masculinity also led me to wonder how we can model and teach behavior that rejects violence and what role sex education could play in this.

And I wanted more discussion of the earliest phases and indicators of domestic abuse, before patterns of escalation, isolation, and dependence become ingrained. It seems to me that this is a crucial area of concern, especially for therapists, counselors, and mental health providers, who can play a critical role in helping victims and their families. Even so, through her understanding and commitment, Snyder offers hope for anyone who’s suffered from or tried to treat those caught in the maw of domestic violence. In underlining the gruesomeness of these stories, she broadcasts the urgency of her endeavor.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.