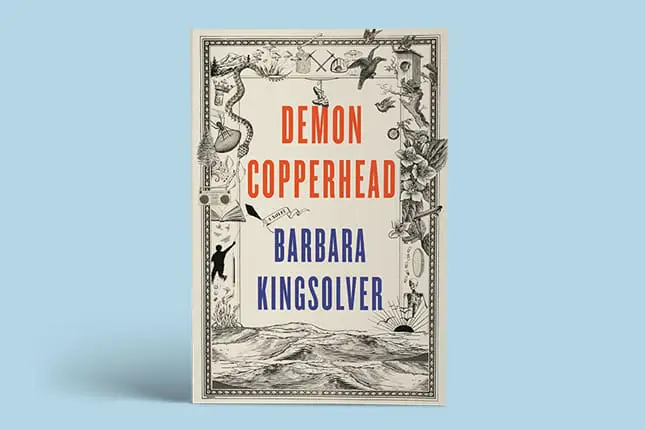

Demon Copperhead

By Barbara Kingsolver

Publisher: HarperCollins

Demon Copperhead is Barbara Kingsolver’s imaginative retelling of Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield. In Dickens’s novel, David lives quietly in an English village with his mother until she marries a cruel man who ships him off to boarding school. His mother dies when he’s nine years old, and thereafter he must fend for himself. Kingsolver’s hero, Demon, is born in the 1980s in rural Lee County, Virginia to an addicted mother who takes up with a brute. Demon’s mother, too, dies suddenly. Both books explore what happens to children when almost everything goes wrong. I predict that Demon Copperhead, like David Copperfield, will become a classic. It brims with brilliant writing, vivid and unique characters, and an exquisite attunement to the human heart.

We can see Kingsolver’s resplendent prose in Demon’s description of U-Haul Pyles, who first appears when he shows up to drive the boy to his third foster home. “A car pulled in, and the guy getting out of it was the weirdest-looking guy I ever saw, not counting comic books. Stick legs, long white arms, long busy fingers that twined all over him. Running through his hair, wrapping around his elbows while he stood looking around the parking lot. A redhead, but not my tribe. He was the deathly white type with the pinkish hair and no eyebrows. That skin that looks like it will burn if you stare at it.”

Reading this description, I can see U-Haul Pyles. He makes my skin crawl.

Demon, on the other hand, is one of my favorite characters in all of English literature. That’s saying a great deal because I’ve been a reader since I was very young. My favorite characters include Francie in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird, O-Lan in The Good Earth, Emma Bovary and Anna Karenina. I can think of only two male characters besides Demon for this list, Dr. Zhivago and Huck Finn. Demon’s plight, his pain, and his pluck hooked me from page one. He’s curious, honest, and full of incisive observations that made me laugh out loud or want to cry. An instance of the latter: at one point, Demon observes, “Anyone will tell you that the born of this world are marked from the get-out. Win or lose.”

I identified with the boy’s hill country background. My father’s family lives in and around Ozark, Missouri and they’re viewed as hillbillies. I know that Southern rural people can feel inferior, as they’re well aware of the J. D. Vance kinds of ideas about why they’re often poor. In Hillbilly Elegy, Vance blames their poverty on laziness and ignorance.

I also identified with Demon’s loneliness and his feelings of being different from other people. I was a clumsy, socially awkward girl from an odd family that moved from town to town. Demon describes being in elementary school and not understanding math and other subjects while, at the same time, living through so much more than his fellow students. Perhaps many of us can identify with that kind of loneliness.

Demon is an ironic name for a vulnerable boy wanting only to be loved and safe. His real name was Damon, but it quickly morphed into Demon. Boys like him are often perceived as low achievers and troublemakers and given diagnoses such as oppositional defiance disorder. However, Kingsolver doesn’t see him from the outside, as a problem to be managed. Because of her fine writing and her capacity for empathy, we see the world through his eyes and heart. We feel what he feels.

Demon’s mother loves him, but she’s hooked on alcohol and opiates and can’t consistently care for him. When Demon is just starting school, her boyfriend, Stoner, moves into their home. To teach Demon “self-discipline,” Stoner emotionally and physically abuses him. Then, Demon’s mother overdoses and is taken to a hospital, which prompts the local authorities to put him in foster care. He says of his life, “At that time, I thought my life couldn’t get worse. Here’s some advice: Don’t ever think that.”

Shortly after his mother returns home, she overdoses again—and dies.

Kingsolver’s attunement to the boy’s heart is reflected in his feelings about his final visit with Stoner. “I was wishing so hard for him to give a damn, and also for him to disappear from the face of the Earth. I wished both things at the same time. And wish number three, not to be the eleven-year-old redheaded boy that everybody saw crying at the burger place on Route 58.”

Demon describes his first foster home as “a slave farm for homeless boys.” Creaky, his foster father, forces Demon and his new friends, Tommy and Fast Forward, to miss school to pick tobacco. On his first day on the job, Demon suffers from green tobacco sickness. At his second home, his foster parents don’t give Demon enough to eat. He dreams about food and draws pictures of his favorite dishes. Even the dog’s food tempts him. In this home, he’s sent to work at a recycling center where one of his jobs is to drain batteries. The acid burns holes in his clothes and scorches his arms. Slowly, he realizes that he’s working in a meth lab.

Eventually, 12-year-old Demon hitchhikes and walks from Virginia to his grandmother’s home in Tennessee. He’s never met her, but he has no one left to help him. This solo trip illustrates the desperate situation of a child without a protector. He’s robbed, falsely accused of a crime, forced to sleep outside in the cold, and weak from hunger. He keeps walking because he has nowhere else to go.

Demon’s grandmother takes him in briefly while she arranges for his care elsewhere. Soon, Demon is sent back to Lee County to live with a high school coach and his teenage daughter, Angus. Coach buys him good clothes and $60 shoes and takes him to football practice. Demon’s association with the coach and his talent for football make him a star at his school. His dizzying rise in status makes him ecstatic, but he doesn’t expect it will last. Nobody keeps him for long.

Then, Demon is crippled by a football injury. A doctor gives him massive amounts of painkillers so he can keep playing football. Eventually, he becomes hooked on prescription opioids and later, heroin. Kingsolver allows us to experience Demon’s grinding, daily existence as an addict. He’s in almost constant physical and emotional pain, seeking relief from an unbearable reality. We experience his craving, his rush, and the woozy, golden melting into forgetfulness that comes with drugs. We feel his despair about his addiction even as we understand why he inflicts it upon himself.

I’ll leave the rest of Demon’s story for readers to discover. His journey includes light as well as darkness. He makes many friends, including a gay neighbor named Maggot, who invites him into his family. Tommy, his friend from the first foster home, encourages him to draw, while Angus, the coach’s daughter, offers him companionship and acceptance. Several adults, including a young social worker and a teacher who recognizes Demon’s gifts, encourage and support him. And his own indominable spirit shines through. Tested repeatedly by fate, Demon simply refuses to give up.

Kingsolver has been writing brilliant books since her first novel, The Bean Trees, was published in 1988. She does what all great novelists do, which is to deepen our understanding of another’s point of view and thereby expand our moral imaginations. Reading novels, we can empathize with people from all over the world. Or, as my Aunt Margaret told me when I was young, “If you aren’t a reader, you will know some people—members of your family, neighbors, and close friends. But if you are a reader, you’ll know thousands of people in all kinds of circumstances.”

For me, the purpose of life is to grow in moral imagination until there is no us versus them and the whole world is in my circle of caring. Being a therapist has helped me move toward that goal, and so have the writings of Barbara Kingsolver.

Mary Pipher

Mary Pipher, PhD, is a clinical psychologist, author, and climate activist. She’s a contributing writer for The New York Times and the author of 12 books, including Reviving Ophelia, Women Rowing North, and her latest, A Life in Light. Four of her books have been New York Times bestsellers. She’s received two American Psychological Association Presidential Citation awards, one of which she returned to protest psychologists’ involvement in enhanced interrogations at Guantanamo.