Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

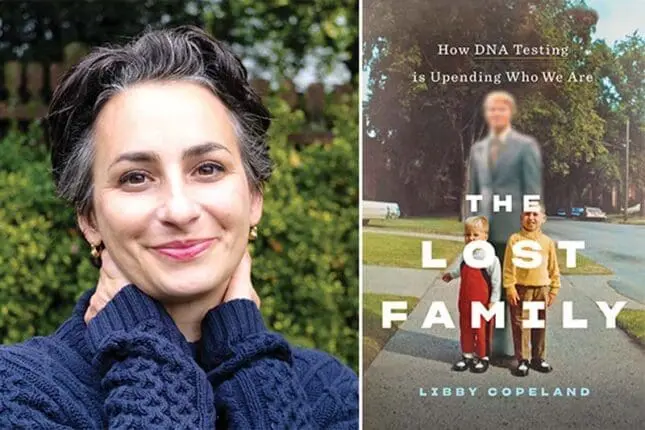

The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are

by Libby Copeland

Abrams Press

294 pages

Spit at your own risk. Sending in a saliva sample to consumer genetic-testing companies such as 23andMe or AncestryDNA can seem like an innocuous lark—until the results arrive, all too often revealing family secrets and setting off unexpected psychic aftershocks that can ripple throughout entire clans.

Yes, we’ve all seen the lighthearted television ad in which a man jovially shrugs off his discovery that the German ethnic identity he’d grown up with was genetically incorrect. Learning that his ancestors were instead Scots-Irish, he accommodates his new identity without missing a beat, simply trading in his lederhosen for a kilt.

But would he still be dancing a jig if the results had exposed a different paternity from the man he called Dad? How easily would he come to grips with the idea of being the product instead of his mother’s infidelity? Or what if his DNA didn’t match either parent, revealing the long-held secret that he’d been adopted? Would he ever be able to regain his balance if the results pointed to the dark and unsavory secret of incest?

More scenarios made possible by DNA home-testing kit results: What if he were approached by a stranger who’d also had her DNA tested, and now, based on their genetic similarity, claims to be a half-sibling he never knew existed? Or what if there were many half-siblings, all fathered, just like him, by a sperm donor his parents had never told him about? Or turn the tables: What if he himself had been the sperm donor, making some extra bucks just like his fellow medical students back in the day—and has no desire to upset his current nuclear family with the addition of offspring who are strangers, no matter their shared genetics?

Those are only a few of the real-life genetic “reveals” that journalist Libby Copeland recounts in The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are, an absorbing, in-depth exploration of the wide-ranging impact of the consumer genetic-testing industry. Using a broad swath of information gathered from testers and testees, she demonstrates that mail-in samples marketed as easy routes to finding family roots are uprooting long-held certainties about personal identity and familial connection. And with the testing business sprouting faster than any family tree—between 2017 and 2019, the number of people taking in-home DNA tests grew from 8 million to about 30 million—who knows how many still-buried surprises await discovery?

To be sure, initial shellshocks can change into newfound connections. Copeland chronicles moving tales about the development of new sibling relationships, the resolution of long-held family-tree mysteries, and the unexpected solace of finding new connections in newly found genetic family members. The point, though, remains the same: you can’t predict what you might find. Regardless of what the happy-go-lucky ads seem to promise, you might end up with a result quite different from the one you bargained for. Copeland wryly notes, “boring results can be a blessing.”

Indeed, statistics suggest we might be more interesting than we thought. Testing companies label surprise discoveries with benign euphemisms like “unexpected relationships” and “NPE,” for “nonpaternal event” (“not parent expected” is the more expansive decoding of the acronym). The estimates of unusual, unanticipated findings range from the low single-digits to as high as 15 percent. Copeland, doing the math for us, writes, “If you assume just three percent of consumers, which is a conservative estimate, spread across 30 million testers in databases, you’re talking close to a million people—and more every day.”

Therein lies the dilemma. How do we cope with incorporating (or not) these new, not-always-fun family facts into our personal narratives of who we are, accommodating those realities into our existing family relationships? Acknowledging how frequent, even commonplace, unforeseen results have become, many companies have beefed up their customer service departments, with employees acting as counselors. At 23andMe, a specially trained team is prepped to answer questions and listen with empathy as consumers voice their struggles with new information. The company has even launched an online page that includes links to psychotherapists.

That’s the least testing companies can do. As Copeland shows, the questions raised by the industry range from the philosophical to the existential, from the realm of ethics to that of etiquette. How does one even begin to tease apart the connecting strands of family identity that have nurtured us, from the biological material carried in our genes? What do our genes actually tell us about who we are, and about the already loaded question of identity—especially in an era already saturated with identity politics based on ethnicity, race, national origins, religion, cultural heritage, sexuality, political ideology, you name it.

And more: How do we weigh the personal need to discover our own biological roots against the privacy of others? How do you even begin asking aging parents about “unexpected paternity” results? Most of all, are there ways to help accommodate and cope with the emotional and familial fallout from revelations that upset and rewrite a long-accepted happy history into a furtive tale of bad behavior?

The unfinished business, unanswered questions, and sense of loss are different from other types of grief, Krista Driver, a California-based psychotherapist and adoptee who used DNA testing to find her biological mother, told Copeland. “There are secrets people don’t want to talk about,” or can’t find a way to talk about, she said. When they come out in the open, the sudden shock can feel profoundly traumatic. It can bring about a relapse in people who’ve been sober for years. And unfortunately, she continued, there’s nothing really in the mental health community addressing this particular kind of identity shock.

But there’s starting to be. Driver and others are leading the way to what might prove to be a new specialty. For instance, therapist Jodi Klugman-Rabb’s website states, “At-home DNA tests like 23andMe and Ancestry.com can come as an unpleasant surprise about a biological parent or your ancestry. Learning that you might have a new family can shake you to your roots. I have had personal experiences along the same lines, and that has inspired me to add Parental Identity Discovery to my practice.” Genetic counselor Brianne Kirkpatrick of Charlottesville, Virginia, coaches NPE recipients as they come to terms with the information, including prepping them to share the DNA information with others in the family, or how best to approach biological family members who don’t yet know of their genetic connection. Various support groups have also come into existence, such as NPE Friends Fellowship, founded in 2018, which now has 7,000 members in 40 countries.

No, as one home-tester told Copeland, DNA is not love. And as we all know, not every family distributes nurture or caring evenly or as fully. But if, as population geneticist Razib Khan predicts, most Americans will have their very own DNA results in hand by the end of 2023, a deluge of unraveled family secrets will no doubt find their way to therapists’ offices everywhere, possibly yours.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.