“Everyone—my friends, my mom, even my last therapist—told me that my relationship with Stephanie was toxic and I needed to leave,” Emily said. “So I did. It took me three years, but I

finally left. Now, it’s worse than ever—and no one

prepared me for this.”

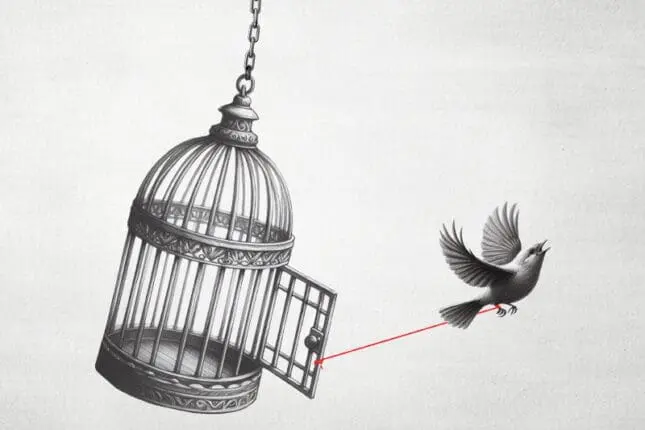

Throughout their 11-year relationship, Stephanie had been emotionally and verbally abusive toward Emily, which had chipped away at her self-esteem and sense of self. Finally, Emily had moved out, but instead of feeling free, she was now experiencing a new level of abuse. Angry and emboldened, Stephanie was engaging in retaliatory and vindictive behaviors: refusing to relinquish information about their joint accounts and investments (which Emily had always trusted to her to maintain), relitigating financial agreements that sent them back to mediation repeatedly, spreading false rumors among mutual friends that Emily had been unfaithful, sending angry texts and emails, and withholding custody of their shared dog, Zora.

No matter how much work Emily and her previous therapist had done around practicing self-care and setting boundaries after the separation, Stephanie kept finding ways to assert her control and keep Emily hooked.

As therapists become more aware of the presence of coercive control in relationships and are better trained in helping survivors leave these relationships, I wonder if enough attention is being paid to the issue of post-separation abuse—because it often masquerades as the simple lashing out of an aggrieved partner whose primary relationship has just ended.

When Stephanie contacted Emily’s mom to share her concern that Emily was depressed, it seemed like the act of a caring ex. And when Stephanie started tracking Emily’s comings and goings through the Uber app Emily had forgotten they shared, it seemed like innocuous snooping to many of their friends. And when Stephanie repeatedly reached out to Emily to accuse her of ruining their family, it seemed like she just needed emotional support from the one person who’d always given it to her. In reality, this was a pattern of behavior rooted in the desire for power and control.

Unfortunately, people have many misconceptions about what abuse looks like. Most think it’s overt, physical violence, or that only men can be perpetrators, or that it doesn’t happen in gay, lesbian, or queer relationships. As Emily’s case shows, the ubiquity of these myths makes the abuse even harder to identify and increases the risk that it can escalate to dangerous levels, especially if it comes after a relationship has ended.

Victim Blaming

From our first session, I noticed Emily making many victim-blaming statements about herself. “I get it,” Emily said after she saw Stephanie driving by her house several times in one night. “I feel bad for her. I’ve been setting firm boundaries around communication, and I think it’s really upsetting her. To be honest, I feel like if I hadn’t been so cold to her at the end of our relationship, she wouldn’t be acting like this.”

Emily had boundless empathy, which is likely part of what had made it so easy for her to fall into a trauma-bonded pattern of feeling responsible for, excusing, and even forgiving Stephanie’s behavior. But that didn’t make Stephanie’s behavior her fault, and I wanted Emily to realize that while Stephanie had taken advantage of her empathy and vulnerability, these were beautiful qualities that I hoped she’d nurture, even as she worked on strengthening her sense of agency and autonomy.

I also hoped that by validating Emily’s feelings and experiences, I could help counteract the isolation and gaslighting she’d been subjected to for so long. “I hear what you’re saying, Emily,” I told her. “It’s tempting to think there’s something you might’ve done to avoid what you’re experiencing. It gives you a sense of power in a situation where you feel powerless. But you’ve worked hard at trying to salvage this relationship, and I think we’ve exhausted all possibilities. It’s clear from Stephanie’s pattern of behavior that this is her problem, not yours.”

Even after a relationship has ended, I recommend that all my clients document all instances of abuse, from gaslighting and belittlement to harassment and stalking. Not only can this documentation serve as a record that might be helpful to law enforcement or used in legal proceedings, including if the survivor needs to obtain a protection order, but it can give survivors a sense of clarity and control when they might be feeling helpless and hopeless.

As we worked together, Emily learned to write things down when she felt herself spiraling in response to something Stephanie would say or do. For instance, every time Stephanie refused to drop off their dog at the agreed-upon time, rather than argue or engage with her, Emily documented it. When one day Stephanie called her 12 times to demand they discuss which of them would attend a mutual friend’s birthday party, rather than getting sucked into Stepahanie’s vortex, Emily just wrote down the incident.

Still, Emily was prone to moments of doubt. She often told me it felt like she was just keeping a petty list of grievances. “Maybe this is normal,” she’d say. “I mean, all breakups are bad, right? My divorce lawyer says he sees these things all the time. He said he’s used to working with ‘high-conflict couples.’”

“There’s a big difference between being a high-conflict couple and being the victim of coercive control,” I responded. “High conflict implies that both people are part of the problem, whereas coercive control involves the systematic manipulation and domination of one partner by the other.” Reminding her of this was part of our ongoing psychoeducation to decrease the shame and self-blame that often accompanies abuse survivors. It came up again and again as Emily explored a question she’d begun to ruminate on: How did I end up in this situation?!

In some ways, it was useful to reflect with her on how her propensity to avoid conflict might have contributed to her dynamic with Stephanie, but too often the rumination about how she could’ve stayed for so long in such an unhealthy situation was counterproductive and only ended in more self-blame. So rather than try to come up with a definitive answer to her question, we took the time to reframe it as a chance to develop self-compassion.

Another part of our work was creating a safety plan, which too many therapists overlook in the case of post-separation abuse if physical abuse hasn’t occurred, since many people wrongly assume that nonphysical coercive control isn’t dangerous. It includes identifying safe spaces, outlining steps to take in case of emergencies, and establishing clear communication protocols with the ex-partner, a crucial component of which involves empowering survivors to minimize nonessential communication with them. Of course, some communication may be necessary, especially when partners share custody of children or must arrange legal proceedings, but minimizing communication is a proactive measure that reduces opportunities for further abuse and trauma.

The Stigma Problem

Over time, with more space from Stephanie, Emily began to realize something essential to her healing: although she wasn’t able to control Stephanie’s actions, she could control her own reactions. Eventually, she started feeling less of the fear, anxiety, and self-doubt that had plagued her for years, and was able to focus more fully on her own well-being.

But despite our progress, she still had to contend with a larger problem: other people’s widespread misunderstanding of coercive control. For instance, the few times that Emily had recounted some of the things Stephanie had said and done, her mom had just shaken her head and declared, “Relationships are hard.” It was as if she’d taken a bystander stance on the abuse, minimizing its seriousness and relinquishing any responsibility to intervene or provide support. “Staying out of it” might’ve been a boundary of her own, but it inadvertently greenlighted the abuse. The more it happened, the more she felt abandoned by her mom, one of the primary supports in her life.

After her relationship with Stephanie had ended, Emily had tried to regain the lost sense of closeness with her mother and explain what she now understood about the dynamics of coercive control. But her mother, while glad to see her daughter more often than she had when Stephanie was around, usually responded with comments like, “Sounds like Stephanie had a tough childhood,” or “If it was really abuse, I think you would’ve left sooner.” Statements like these only echoed Emily’s self-blame and didn’t account for the power dynamics at play in coercive-control situations or the immense courage and strength it took to escape an abusive relationship.

To counteract the messages she’d received from her mom, I listened to Emily’s experiences without judgment and reinforced that her emotional responses to the challenges she faced were understandable, and even expected, given the dynamics of coercive control. I validated the self-doubt, confusion, and isolation she’d been feeling, while reminding her to speak kindly to herself to minimize these feelings. Modeling compassion helps clients develop self-compassion, so they can go on to create self-care practices and rebuild a positive relationship with themselves.

Again and again, Stephanie would test Emily’s boundaries. But thanks to our work and a new support network of trusted friends, Emily continued to unlearn the messages she’d internalized for so long. “I realize now that I didn’t deserve retaliation for ending the relationship,” she told me. “And I know I need to be kind to myself as I heal. This was a traumatic experience.” Even if the rest of the world wasn’t ready to hold abusers accountable, Emily would be.

In many ways, Emily’s journey was healing for me, too. I know how difficult it can be to recognize post-separation abuse because I’d failed to recognize it when it had happened in my own life. Like Emily, I experienced moments of denial. They’re just mad right now, I thought. When I finally sought help, other people, including law-enforcement personnel, reinforced these thoughts. “This is normal breakup stuff, ma’am,” one officer told me. “Just try to ignore it.” Friends said similar things, assuring me that it would “blow over soon.” Some even asked what I’d done to make my ex so angry. While I’m sure they didn’t mean any harm, their lack of support kept me feeling isolated and second-guessing myself.

I lost sleep, afraid to open my email or answer calls, and my heart raced every time a car slowed down by my house. I lived in constant fear of what new form of retaliation might be waiting around the corner. I don’t know what I would’ve done if I hadn’t eventually found a therapist who understood coercive control and helped me decrease the shame and self-blame that had become a part of me.

Today, I feel grateful to have the knowledge and resources to educate others about the truth of post-separation abuse. Even therapists who consider themselves skilled in working with abuse survivors continue to use terms like high conflict and mutual abuse, reinforcing the message that survivors are somehow contributing to the problem. I’m glad that our field seems to be having more honest conversations on this topic, but we still need to do better. Survivors depend on it.

Kaytee Gillis

Kaytee Gillis, LCSW-BACS, is a psychotherapist, writer, and author with a passion for working with survivors of family trauma and IPV. Her work focuses on assisting survivors of psychological abuse, stalking, and other non-physical forms of domestic violence and family trauma. Her recent book, Invisible Bruises: How a Better Understanding of the Patterns of Domestic Violence Can Help Survivors Navigate the Legal System, sheds light on the ways that the legal system perpetuates the cycle of domestic violence by failing to recognize patterns that hold perpetrators accountable.