Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

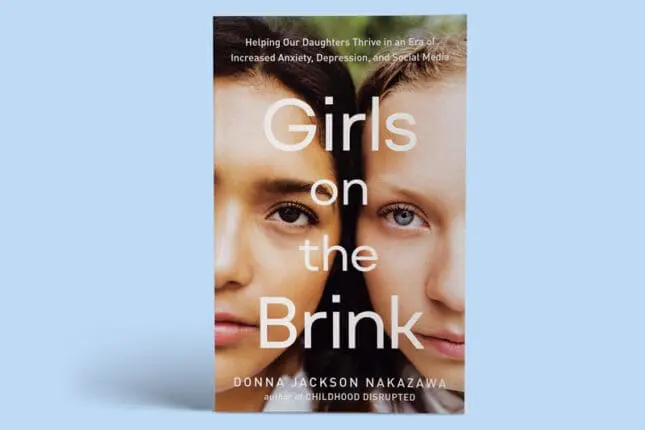

Girls on the Brink

Helping Our Daughters Thrive in an Era of Increased Anxiety, Depression, and Social Media

New York: Random House/Harmony Books, 2022

By Donna Jackson Nakazawa

Before I even opened Girls on the Brink, I was drawn to the title because it so clearly names the cliff’s edge that today’s girls teeter on, a narrow ledge between possibility and peril. But the subtitle, Helping Our Daughters Thrive in an Era of Increased Anxiety, Depression, and Social Media, seems entirely too modest. I think it underplays the great contribution of the book, which plumbs the neurobiology of girls’ higher risk for mental health troubles compared to boys and shows how we adults can use that knowledge to help pull girls back to safety.

Author Donna Jackson Nakazawa, a journalist who’s written several books on the intersection of neuroscience and mental health, opens with some jarring statistics. One out of every 4 teen girls struggles with symptoms of major depression, compared with fewer than 1 in 10 boys. Girls are twice as likely as boys to suffer from anxiety. Nearly half of young women report up to 10 days of “poor mental health” during the preceding month, compared to 28 percent of young men. On and on. If we dismiss the disparities as due mostly to sex-linked differences in reporting or help-seeking, we do girls a grave disservice. The author frames the situation as a state of emergency: if therapists, parents, and other adults don’t address the depth and breadth of girls’ suffering, too many of them will get lost and stay lost in adulthood—if they make it that far.

So why are girls struggling more than boys? After all, nearly every adolescent faces stress these days—pressure to achieve, fears about the future of the planet, angst about peer acceptance, and, intensifying it all, the relentless buzz and clatter of social media. Certainly, boys suffer, too. But the author points out that when girls reach puberty, they’re coping with these pressures in the face of a potent new factor—the influx of estrogen. When a girl is under persistent stress, this hormone can rachet up her vulnerability to emotional distress. (For the purposes of this book, the author examines differences between cisgender girls and cisgender boys, while acknowledging that sex and gender roles can shift or change.)

But before we wade too far into biological waters, the author stops the action to clarify a vital point: the interplay between estrogen and mental health risk has nothing to do with some inherent “weakness” housed in the female body, as has been conventional wisdom for millennia. She argues just the opposite: the influx of estrogen at puberty has been a life-saving, evolutionary strength of girls and women. To survive in hunter-gatherer days, every human being had to be finely attuned to predator danger. But Jackson Nakazawa points out that for females of childbearing age, the stakes were considerably higher than for males, because women needed to stay alive and healthy long enough to nurture their offspring over many years—and to achieve that, they needed their tribe’s protection. So females evolved to be hyper-attuned to social and emotional threats of rejection by their community because exclusion could be fatal to their entire families. Fast-forward to the noisy, near-constant assaults on teen girls’ sense of belonging and self-worth via social media and you have a prescription for rising anxiety, a diminished sense of safety, and, in some cases, outright despair.

Jackson Nakazawa is nothing if not thorough, and she takes pains to document the complex chain of biological events that can transform felt rejection and other forms of devaluation into severe emotional distress—what she calls “the damage cascade.” This process starts with an estrogen-fueled stress response, which produces heightened immune activity, in turn prompting a spike in inflammation that, over time, can trigger epigenetic changes that increase vulnerability to mental health troubles. If this sounds complicated, it is. But the author presents the neurobiological domino effect in lucid and meticulous detail, while taking care not to oversell her argument. “This is science in motion,” she says, with much still to be learned about the bodily processes that influence sex differences in mental health. Her blend of humility and careful reporting make her both a reliable narrator and a teacher with high standards, one who refuses to oversimplify her material for the sake of easy consumption.

As someone who tends to look first and foremost at the psychological dimensions of behavior, I initially struggled with Jackson Nakazawa’s intricate layering and sequencing of brain-body influences. But I came to see their value as she builds, brick by brick, a feminist-informed case for the way that evolutionary imperatives, in tandem with the day-to-day affronts of sexism and the body’s stress response, sets girls up for emotional distress.

The most vital conclusion of Girls on the Brink is that the intersection of female biology with a patriarchal society makes many girls feel fundamentally unsafe—and that lack of safety can spiral into hazardous levels of misery. The beguilements and judgments of social media are a big factor in this chronic sense of endangerment, but so is a culture that puts girls at constant risk for sexual harassment, abuse, and a host of other assaults on their fundamental security and self-worth. Jackson Nakazawa tells it straight: if we imagine we’re now living in a reasonably gender-equal society, we’re wrong. To help drive her point home, she quotes pediatric researcher Robert Whitaker, author of numerous studies on sex differences in young people’s mental health. He observes, “The data very much hold the possibility that gender is a trauma for girls.”

In my own teenage years, I struggled with persistent depression, and reading this book helped me connect the self-castigation and helplessness I felt then with the relentless injunction to please men and the attendant reflex to swallow my voice, even at great emotional cost. What Jackson Nakazawa calls “the patriarchal machine” isn’t just a social engine perpetuating unequal wages and unshared housework: for many girls, it produces nothing less than a sense of obliteration. Today, this threat of felt annihilation continues to hover over girls, but now at earlier ages and with greater ferocity, courtesy of social media.

So what’s a reader to do? First, Jackson Nakazawa says, we need to stop pretending that things are more or less okay. As the adults who’ve helped create—or at least tacitly accept—the perilous world girls live in, it’s up to us to restore a sense of shelter and agency. And with sufficient will, we can: the data show that girls are more susceptible to mental health problems only when their sources of stress remain unaddressed. Perhaps not surprisingly, research consistently documents that feeling safe with and connected to a caring person during one’s youth is the single most important ingredient in adult mental health.

Here Jackson Nakazawa pivots, devoting the second half of the book to steps that parents and other key adults in a girl’s life can take to create that vital experience of safety—which, in turn, can free up space for a young woman to take charge of her life. While the remedies Jackson Nakazawa proposes are aimed primarily at parents, many have sufficient psychological depth to serve as useful tools for therapists working with families. Her first recommendation to parents who want to support their daughters is to face and deal with their own unaddressed histories of adversity and trauma. Her tone here is gentle but firm: “If you never felt safely seen or nurtured by your own parents, how can you, in turn, learn to offer this gift to your own child?” She argues that no amount of love can suffice to help a young person thrive unless a parent can provide an attuned, nonreactive presence in the face of that child’s turmoil. She cites a stunning piece of research: data from the National Survey of Children’s Health shows that the odds that children will flourish throughout their teen years are 12 times higher for kids whose parents answer positively (“very well”) to a single question: “How well can you and your child share ideas or talk about things that really matter?”

The author presents a number of other thoughtful strategies for helping young women thrive, among them supporting them in developing “a voice of resistance” in response to any person or system that tries to undermine them. This section includes a memorable parent–daughter role-playing script, in which the parent plays a man making sexist remarks and the daughter responds with fearless, devastatingly on-point retorts. Further on, the author makes a strong case for the value of psychotherapy, citing a meta-analysis of 51 randomized trials that shows that working with a therapist is associated with improvements in immune health and lower levels of distress-activating inflammation.

Our persistently sexist society will continue to stalk young women: in the author’s words, “the world will find them.” It’s a chilling thought, but not one that should deter us. We adults hold the responsibility and the power to equip our girls to fight back, marshal support, and walk in the world with agency and even joy. And we have no time to lose. Too many girls are faltering, and more of them are giving up every day.

“It’s past time,” says Jackson Nakazawa. “Time is really up.”

It’s hard to come away from this thoughtful, quietly passionate book and believe otherwise.

Marian Sandmaier

Marian Sandmaier is the author of two nonfiction books, Original Kin: The Search for Connection Among Adult Sisters and Brothers (Dutton-Penguin) and The Invisible Alcoholics: Women and Alcohol Abuse in America (McGraw-Hill). She is Features Editor at Psychotherapy Networker and has written for the New York Times Book Review, the Washington Post, and other publications. Sandmaier has discussed her work on the Oprah Winfrey Show, the Today Show, and NPR’s “All Things Considered” and “Fresh Air.” On several occasions, she has received recognition from the American Society of Journalists and Authors for magazine articles on psychology and behavior. Most recently, she won the ASJA first-person essay award for her article “Hanging Out with Dick Van Dyke” on her inconvenient attack of shyness while interviewing. You can learn more about her work at www.mariansandmaier.net.