In my first memory of shyness, I’m four years old and bolting across the street from my friend Bonnie’s house back to mine—never mind that I’m not allowed to cross the street by myself. What had just happened was that Bonnie’s father had come home from work and poked his head into the playroom, where we were kneeling on the floor making a town out of wooden blocks. “Hi, there, girls!” he said, smiling a friendly daddy smile.

I looked up and saw a tall man in a topcoat and go-to-work hat, a man I’d never seen before except from far away, when he was mowing his front lawn or bending over his flower garden. In half a second, I’d shot out of the room, banged through Bonnie’s front door and raced across the street as fast as my skinny legs could take me.

My instinct to hide in the presence of new people—to either go still as a statue or make a run for it—dogged me throughout childhood and followed me, in a more covert form, into young adulthood. I was able to make friends and get jobs, thanks to a lucky knack for faking confidence until I actually felt some. But secretly, first encounters filled me with terror. I couldn’t imagine anyone wanting to talk to me, and the prospect of rejection felt unbearable. My social modus operandi was simple: when possible, say no. And very often I did, missing chance after chance to meet new and potentially like-minded people, and to get ahead in my work.

Work. It was important to me. I wanted to be a writer, badly. A couple of years after graduating from college, I got a job with the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, a newly formed federal agency in charge of preventing drinking problems. I was an information specialist—which, as I understood it, involved sitting in an office minding my own business while writing useful public education materials. Perfect. I moved from Philadelphia to Washington, DC to take the position, and for about two months my assignments—library research and writing, then more library research and writing—were right up my introverted alley.

Then one morning, my boss called me into her office. When I walked in, this normally unflappable woman was practically levitating with excitement. “The institute is planning a big public education splash,” she said. “We’re going to create a special magazine on preventing alcoholism that will be published in Sunday newspapers all over the country!”

“That’s great,” I said sincerely. “What would you like me to write?”

She looked at me intently. “Well, if we expect anyone to actually read it, we’ll need a big name.” And then she dropped the bomb: she wanted me to locate, interview, and then write about a recently recovered alcoholic named Dick Van Dyke. Yeah, that guy. The megafamous comic actor. Star of his own, outrageously successful TV show. Winner of a Tony, a Grammy, and five Emmys.

I felt a momentary jolt of elation: Dick Van Dyke! But then my stomach twisted, hard, and I was four years old again, desperate to get to safety. “I’ve heard he’s almost impossible to get in touch with,” I said, furrowing my brow in fake concern. “He’s, you know, notorious for that.”

My boss’s lip didn’t exactly curl, but it might have twitched. “Try,” she said.

I trudged back to my office. There was no getting out of this. Not if I wanted to keep my job. Not if I wanted to go anywhere with my writing. This was known in the journalism business as a break, not a catastrophe. Stepping up to assignments was Rule One.

But what were the chances I could even make contact with the likes of Dick Van Dyke? I was an obscure functionary at a government agency, not The New York Times. His phone number, of course, was unlisted. Finally, I dug up a post office box number in Cave Creek, Arizona.

So, I did what a person could do in the 1970s, which was to sit down at my electric typewriter and write him a request letter, trying to come across as simultaneously admiring (which I was) and totally understanding if he didn’t want to do an interview with me (equally true). I pasted a 10-cent stamp on the envelope and mailed it off.

About two weeks later, I was sitting in my office drafting some pamphlet or other on responsible drinking, when my desk phone rang. I sighed at the interruption. “Hello?” I said, my tone extra brisk.

“Hi,” said a rich, resonant voice. “This is Dick Van Dyke.”

“Yeah, and I’m Mary Tyler Moore,” I nearly quipped, annoyed that someone in my office was pranking me. Luckily, in the next millisecond, I canceled that response. Instead, I said, “Oh.” Continuing to display my crack conversational skills, I added, “Thanks for calling.”

Van Dyke wasted no words. “I got your letter, and I’d be glad to do the interview,” he said. He’d be in Los Angeles on such-and-such a date and could get together at such-and-such a time. We agreed to meet up in the lobby of my hotel.

When I hung up the phone, I temporarily forgot I was shy. Exploding out of my office and sprinting up and down the hall, I shrieked, “I just talked to Dick Van Dyke!” Bureaucrats poked their heads out of offices. My boss hugged me.

Ten days later, I flew from DC to Los Angeles and settled into a ridiculously ornate, government-paid suite at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, with a spacious front room attached to the bedroom. Fifteen minutes before the scheduled interview I rode down the elevator to the lobby to wait, my heart knocking. To my astonishment, Van Dyke was already standing there, hands in pockets, wearing a black turtleneck beneath a herringbone sports jacket. He had the quiet, unassuming air of a regular guy.

When I walked over and introduced myself, he shook my hand and grinned his famous grin. Then he ducked his head a fraction and looked off to the side, biting his bottom lip. In the awkward silence that followed, it hit me that this man, this colossal comic celebrity, was shy, too. We stood there tongue-tied, like two people trapped on a bad blind date. Finally, I said, “Okay, so. Should we go up to my suite?” No, you didn’t say that, I hissed at myself.

“Sure,” he said, gazing at a spot above my left shoulder. On the elevator up, we stood side by side, staring straight ahead.

But soon after we entered the suite’s front room, something shifted. As Van Dyke folded his long body into a chair and lit his first cigarette, his self-consciousness seemed to melt away. When I asked my first question—“How do you think your drinking problem got started?”—he plunged right in, describing his gradual transformation from a guy who enjoyed a drink or two in the evening to a desperate, addicted man. The story he told me was stunningly at odds with the image he’d presented on the hugely popular Dick Van Dyke Show and the first Mary Poppins film—that of a slightly cornball, perpetually sunny kind of guy. Instead, he drew a portrait of a tense man who never drank on the set but could hardly wait to get home each evening, at which point he’d promptly open a bottle of high-proof something or other and drink himself into near oblivion.

Furiously taking notes, I asked Van Dyke how he’d arrived at his moment of truth, when he’d realized he couldn’t cope any longer and needed help. He paused. “I’d always been a very happy, lively kind of a drunk,” he said. “Then I began to get angry and aggressive, just a sudden personality change. I frightened myself.” But he kept on drinking until he’d become so physically depleted and mentally confused that he could barely work. Finally, late one night, he was sitting on his living-room sofa totally plastered, “and I realized I couldn’t form a single coherent thought.” The next morning, he checked himself into a treatment program.

I was so riveted that I found it even harder than usual to form full sentences. “Could you . . . I mean, did you . . . so, were you able to quit for good? Right then? I’d think it might be hard to, you know. Make a complete break?”

He turned away slightly. There was a small silence. “Yeah, for a while I had a hard time,” he said finally. “I had a couple of slips. But I managed to get over them.” He nodded, as though to himself. “I got help again.”

Then he cleared his throat and turned his gaze back to me. “Which, incidentally, no one knows about. This is the first time I’ve ever talked about it.”

When Van Dyke said that, something in me woke up. I felt insignificant—in a good way. I couldn’t have articulated it then, but I somehow got that this whole experience had nothing to do with me and my own angst-ridden inner dramas. What I was witnessing was this man blowing past his own deep reserve to share something profoundly personal about himself, something that was brutally stigmatized but, because he was naming it out loud, might actually change a life. You out there, he was saying, if you’re drinking too much, don’t wait until you’re as wrecked as I was. To hell with what other people think. Save your own precious life.

I felt something crack open inside me, something small and not quite conscious. Only later did I understand that in that moment, I’d begun to revise one of the big stories of my life, the one that insisted, I’m shy, so I can’t possibly do that. Now, a different voice was quietly proposing, You’re shy, and so what? Go ahead and be awkward. Be uncomfortable. To hell with what other people think. Show up anyway. Because you never know when you might do some good.

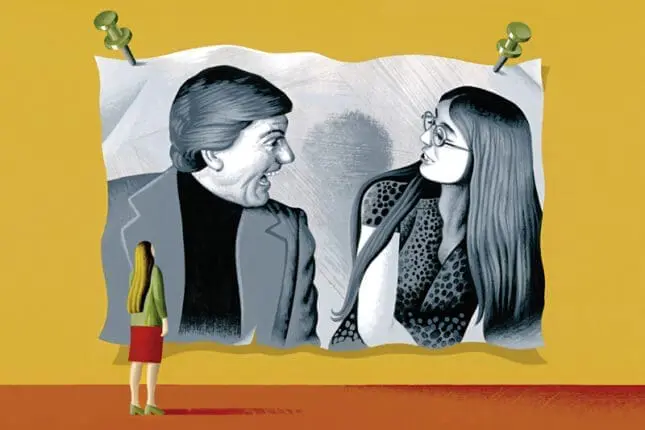

By the time we’d wrapped up the interview, a photographer had arrived and begun to snap pictures of the actor to accompany the article. Unexpectedly, he motioned to both of us. “How about I take a couple of shots of you together?” When Van Dyke nodded, my heart practically stopped, and then I heard the photo guy say, “Make like you’re having a normal conversation.” Instantly, flashbulbs started popping in our faces and, somehow, I found myself hurtling past my panic and launching into a story about how I’d expected to stay at some bleaked-out Motel 6 for this trip, and then got booked instead into the Beverly Wilshire. Crazy, right?

At practically the same moment, Van Dyke and I began to laugh. Crack up, actually. The story wasn’t that funny, but he was a generous man, and in that moment, as we locked eyes, I felt a small tremor of joy. Click, flash. The photographer was kind enough to send me a few of the shots, and one still hangs on my office wall. In it, I’m delivering the punchline of my story and Van Dyke is laughing, open mouthed, like it might just be the most hilarious thing he’s ever heard.

To this day, every now and again I walk by that photo and back up, taking another look. I do it to remember. Because that scared, self-doubting girl still lives inside me. She’s grown up a ton, no question. But sometimes, when a new challenge pops up, I can feel her quaver, cautioning me not to put myself out there and look foolish. Urging me to cut and run.

And the photo says, hey, slow down a minute. There’s more to that story. See that warm, laughing, storytelling woman? Hanging out with—hello!—Dick Van Dyke?

She’s you, too.

ILLUSTRATION BY ADAM NIKLEWICZ

Marian Sandmaier

Marian Sandmaier is the author of two nonfiction books, Original Kin: The Search for Connection Among Adult Sisters and Brothers (Dutton-Penguin) and The Invisible Alcoholics: Women and Alcohol Abuse in America (McGraw-Hill). She is Features Editor at Psychotherapy Networker and has written for the New York Times Book Review, the Washington Post, and other publications. Sandmaier has discussed her work on the Oprah Winfrey Show, the Today Show, and NPR’s “All Things Considered” and “Fresh Air.” On several occasions, she has received recognition from the American Society of Journalists and Authors for magazine articles on psychology and behavior. Most recently, she won the ASJA first-person essay award for her article “Hanging Out with Dick Van Dyke” on her inconvenient attack of shyness while interviewing. You can learn more about her work at www.mariansandmaier.net.