Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

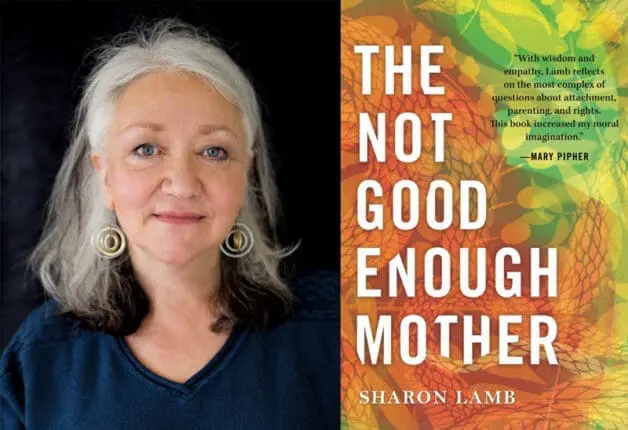

The Not Good Enough Mother

by Sharon Lamb

Beacon Press

“I take children away from their parents. Sometimes permanently.” That’s psychologist Sharon Lamb’s blunt description of her work evaluating the fitness of parents who’ve already lost, or are at risk of losing, custody of their children. It’s her job, as a consultant and expert witness for the Vermont Department of Children and Families, to advise what’s best for these kids. Opioid addictions have cost most of these parents their rights to their children, but in most cases these mothers and fathers are sincere in their desire to turn themselves around. They hope to become dependable, drug-free caregivers, capable of providing safe, stable family environments.

Still, the responsibility of deciding about the custody of a child makes Lamb uncomfortable. She can only predict the best outcome, not ensure it. No matter the hours she spends observing, interviewing, and testing children, their biological parents, and their foster or prospective adoptive parents—as well as talking to concerned teachers, friends, and other relatives—she nonetheless worries that she may err. At a more basic level, she wonders: who is she to judge?

After all, she confesses that she herself had overlooked and denied the signs and symptoms of addiction even as her own adolescent son’s drug use grew into a full-blown habit. Only in retrospect can she see how willfully blind she was to her son’s lies and excuses for “borrowing” (stealing) cash from his parents’ wallets, and for “pawning” (pilfering) household furnishings needed to finance his next fix. She castigates herself for what she perceives as her own failure as a mother. She compounds her self-blame with the taunt that her years of professional training as a child psychologist seemed to have taught her nothing.

That blame is at the heart (and heartbreak) of Lamb’s memoir, The Not Good Enough Mother, but it’s not her sole focus. She uses her story, and the stories of the families she evaluates, as jumping-off points to reflect on what it means to be a parent who is “good enough” and to be judged fit. In doing so, she also shows the importance of learning to forgive oneself for being only good enough.

The concept of the good enough parent, Lamb explains, originated with British psychoanalyst and pediatrician D. W. Winnicott, who famously said that there were no “good mothers,” only “good enough mothers.” No one can be a perfect parent, he reasoned; that’s an impossible, unattainable ideal. Being “ordinarily devoted” is sufficient.

Winnicott put forth this notion in 1953, in the midst of the postwar baby boom and feminine mystique era, when women were expected to more than ordinarily devote themselves to their roles as wives and mothers. In this context, the phrase in and of itself acted as a reassuring reminder that meeting most of your child’s needs most of the time is mostly good enough.

That idea echoes with even more relevance today, in our contemporary frenzy of superparents, tiger parents, and helicopter parents. Winnicott’s phrase sends a strong message that it’s okay to opt out of competitive parenting. Too bad it wasn’t heeded by the wealthy parents accused in a recent scandal of bribing college officials to get their kids into prestigious schools! These parents may claim to be guilty of no more than striving to do their best for their offspring, but it’s difficult not to see the real fuel motivating them as the self-serving desire to outparent everyone else. Wouldn’t the kids have been better served if their parents had focused simply on being “good enough”?

Then again, translating the rather vague abstraction of being a good enough parent into the actual day-to-day interactions between parents and their kids is easier said than done. Certainly, Lamb muses, one essential ingredient is cultivating the ability to mirror the child’s expressions, thoughts, and emotions—something she did in abundance with her son Willy when he was a baby. Rather than consoling her, though, the thought triggers her deep sense of failure: had she somehow misinterpreted his moods, his needs, thereby reflecting back to him her own needs and moods, not his? “Did my watchfulness create an unease that needed soothing with drugs?” she writes. She frets, too, if as a working mother she devoted too much of herself to her career, and not enough to her child.

These self-reflexive questions can be cloying and sometimes obsessive. But they also derive from the genuine curiosity of a researcher seeking answers. In the broader perspective of societal expectations for women, they voice working women’s continuing fear (still!) that they don’t measure up in either their maternal or professional roles. And they demonstrate how difficult it can be to truly internalize Winnicott’s catchphrase, to accept that as parents we did do enough, and perhaps more than that—especially when our children’s failures of judgment or bad behavior, or worse, overwhelm us with unending guilt, blame, and doubt.

Thus, Lamb may know intellectually that the near-ubiquitous presence of drugs today means that no matter how strong the parenting, teen culture can provide opportunity and pressure galore to experiment—with drugs of higher-than-ever potency and toxicity. At a gut level, though, logic isn’t enough to dislodge the instinct of maternal responsibility—which explains why Lamb’s personal second-guessing comes to the fore, unbidden, and perhaps inevitably, as she pursues her professional evaluations and judgments.

Her own story only trickles out slowly, as the recounting of the details of one professional case, and then another, triggers memories and questions that reverse her role from judging others to judging herself. This intermixing sometimes makes it difficult to tell whose story she’s really telling. And perhaps that’s her point: her own experiences have expanded her understanding of the families she works with, and the challenges they face provide insight into her own.

Although the intertwining of her personal and professional sagas aren’t always seamless, she brings a deep understanding to the case histories she sprinkles throughout, leading readers through them step by clinical step, as a teacher would. (In fact, she’s a professor of counseling psychology at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. She’s also the author, coauthor, or editor of 11 books on such subjects as trauma, childhood, and sexual adolescent development.)

She emphasizes the need for empathy, regardless of the accusations against a client. “My students don’t understand how I can sit in a room with a sex offender or wife beater and enjoy his company,” she writes. “It’s not that I believe their denials or their minimization of the violence they perpetrated. . . . But they are more than that.” This is something that gets more fully revealed as she learns the larger stories of their lives, their disappointments, and the love they carry for their children.

At the same time, her empathy doesn’t mean she’s a total softie. “The detachment needed to be a good therapist and still an empathetic therapist is difficult to achieve,” she writes. “In my own work as an evaluator, I must always be vigilant to not punish a mother as I might punish myself or rescue a child who reminds me of my son; to not overvalue a father’s contribution because I miss my own father; to not undervalue a child’s love for her mother because I don’t recall the loving moments between my own mother and me.”

She strives for a similar balance between objectivity and care in gauging a mother’s intense longing to regain custody of her child against the inner resources that parent may, or may not, be capable of providing. The answers she seeks are endless: “Can she cope with stress? Can she cope with life? Does she have smarts? Planning? Patience? Creativity?” Her bottom line in making decisions is whether or not a parent—biological, foster, or adoptive—can provide the child with a stable home in which to thrive and flourish.

Ultimately, though the push–pull between the warmth of understanding and the detachment required for judgment can make even seemingly obvious custody decisions wrenching. Lamb recounts the story of Angela, whose childhood consisted of one horror after another: regular beatings by her violent, alcoholic mother, sexual abuse perpetrated by relatives and household visitors, and sudden abandonment by her mother—all endured by the age of 10. That traumatic personal history can’t help but elicit sympathy. Angela’s young school-age son Nate has also been traumatized, by a stepfather who savagely beat and punished him, and Nate has been further damaged by Angela’s own inability, or refusal, to intervene and protect him. In response, Nate regularly spaces out and has begun biting his hand so hard that it bleeds.

“I can’t support returning Nate to Angela,” Lamb writes, recommending he be adopted by someone who will help address his posttraumatic stress. Yet she’s still so drained by what she describes as her “evaluator’s kind of trauma” that she spends the evening soothing herself with junk food and reruns of Law and Order.

Lamb is particularly acute as she recounts her harrowing odyssey in search of affordable and effective rehab for her son Willy’s addiction. She learns, to her dismay, that many rehab centers have high relapse rates. Worse, she discovers, as she speaks to representatives of one rehab facility after another, “buying a stint in rehab is like buying a new car. There are salesmen and women who sound like they care. They sell options and accessories, and have better or worse deals. You have to haggle with them, but who would know that at the start?”

Fortunately, Willy’s initial treatment did work—at least until a relapse that sends Lamb off to Europe to help rescue him there. But though the worry of another stumble never leaves Lamb, in recent years Willy has not only stayed clean, but found a loving partner with whom he’s raising two kids. This outcome is surely good enough.

Yet Lamb’s second guessing may not be at an end. Just as she’d finished writing this book, her younger son, Julian, died from an accidental drug overdose. “My story as a mother, Willy’s story, remains the same,” she writes. “But now, in my life, in my family’s, everything has changed. Irreversibly. Unfathomably.” She hopes to write that story one day, too. One can only imagine her grief, and admire the courage it will take to continue to play her pivotal role with deeply troubled families in the shadow of tragedy in her own.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.