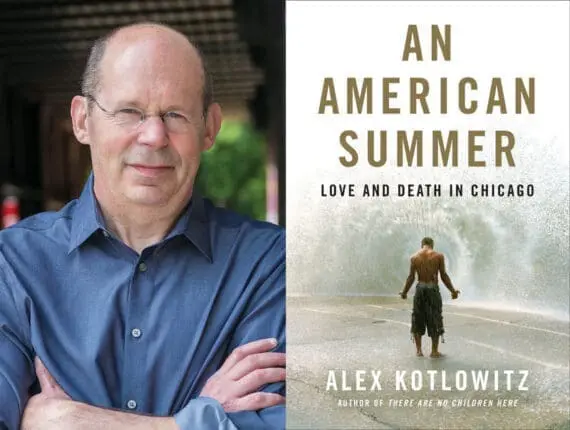

An American Summer: Love and Death in Chicago

By Alex Kotlowitz

Nan A. Talese/Doubleday

304 pages

978-0385538800.

In the United States, black males ages 10 through 19 are nearly 19 times as likely to be murdered than white males of the same age, and are at a comparable risk of being killed as adolescent boys in war zones like South Sudan.

I’d come across that staggering number while writing a piece about the 2017 UNICEF report on global violence against children, and it inescapably returned to mind as I read An American Summer: Love and Death in Chicago by Alex Kotlowitz, a book that could not have more chillingly brought this statistic to life.

Without traveling to a foreign conflict, Kotlowitz has made the urban war zone of Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods his career beat. This is his fourth book focusing on the cumulative psychological and physical toll endured by families and communities caught between entrenched poverty and street violence. His best-known work is the deservedly acclaimed There Are No Children Here: The Story of Two Boys Growing Up in the Other America, published in 1992. There he follows the childhood and adolescence of Lafeyette and Pharoah Rivers, whom readers first meet when the boys are 11 and 9 and already wondering if they’ll survive until adulthood, and weighing the consequences of joining, or avoiding (and if so, how), the drug and gang culture surrounding them. As their mother told Kotlowitz, “There are no children here. They’ve seen too much to be children.”

In this latest book, as in his previous ones, the backdrop is a story of urban blight, societal neglect, and ubiquitous violence that for decades has plagued so many of America’s inner cities. Chicago, Kotlowitz tells us, recorded more than 14,000 murders between 1990 and 2010—a figure that tops the combined total of Americans killed in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. He presents a domestic comparison that’s just as shocking: Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods lose, in one year, twice the number of people killed in the 2012 Newtown school massacre. And among America’s cities, Chicago’s stats aren’t even the worst. “If you’re black or Hispanic in our cities,” he writes, “it’s virtually impossible not to have been touched by the smell and sight of sudden, violent death.”

Kotlowitz is more than aware that citing numbers by themselves can seem abstract, at once a blur of misery and a warning to stay away. Instead, he comes closer. He trains his focus on individuals, spending hours in conversation with them, along with their families, friends, and neighbors, as well as concerned teachers, counselors, therapists, and social workers. His intensive, detailed reporting not only allows but compels us to see their faces, hear their voices, and begin to understand the plight of those trapped in the crossfire. Their stories, told by Kotlowitz with compassion and honesty, constitute wrenching portraits of people searching for, and sometimes even finding, a shard of hope, a glimpse of redemption, amid chaos.

Because the basic neighborhood terrain is the same in all his books, An American Summer can be seen as part of an ongoing project. But it also stands strongly on its own to reveal the impact over time and through generations of the ongoing, grinding trauma and numbing despair that wear on those living within any kind of war zone. Perhaps most remarkably, Kotlowitz discovers in these lives possibilities for resilience, adaptation, and meaning, despite the most dire circumstances. Through his in-depth interviews, he uncovers unexpected pathways to getting through to the most damaged or troubled victims, and unusual strategies that have brought support and solace to the grief-stricken.

Kotlowitz structures his book as the chronicle of a single summer. Each of its 20 chapters—one for just about each week from the beginning of May through mid-September—explores the life stories and daily struggles of individuals doing their best with the hand that circumstance has dealt them.

In “Mother’s Day,” we meet Lisa Daniels, almost 50, as she strives to get through the first Mother’s Day after the shooting death of her 25-year-old son, Darren. Her loss had been acute, but she’d also been struck by all her son and the young man later convicted of murdering him had in common, including a history of drugs and weapons charges. In a different circumstance, she realized, the roles of victim and killer could easily have been reversed. This kernel of insight led first to compassion, then to forgiveness, and subsequently to the remarkable victim-impact statement she wrote on behalf of her son’s murderer, and to correspondence between the two, in which she offers to help him find a job when he’s released from jail.

In this chapter, Kotlowitz also introduces us to Kathhryn Bocanegra, a Chicago social worker who runs two support groups for mothers mourning children who died violently. She describes the complex form of loss experienced by these women as a form of trauma that’s not “post” traumatic, because living in these communities is to exist within a sphere of continuing trauma with no letup. This gives context to the term compassionate relief—a feeling some experience of being spared the further anxiety of what might happen, because the worst already has.

But too often, relief doesn’t take hold. “I’m not afraid of dying,” says Philip, a resident in his 40s at a halfway house for men coming out of prison. “What I’m afraid of is losing my mother, of being in prison, of being a failure. I’m afraid of living.” When he was 13, he and his mother witnessed the deliberate firebombing by neighborhood kids of the house next door. The arson had been the endgame of a minor spat that had escalated way beyond control, just like the fire itself, which spread so quickly that within minutes it had killed Philip’s aunt and three cousins.

He couldn’t kick his sense of self-blame and shame for having not acted to save them—no matter that it would have been suicide to do so—and within months he’d become hooked on heroin. “The heroin was the only way to cope,” he told Kotlowitz. He was also suffering constant flashbacks to the night of the fire. “I’m sitting here with you, but in my mind I’m there, experiencing everything associated with that moment. The feelings, the smoke, the sirens, the crying.” The smell of anything burning remains a visceral trigger.

His story shows the struggle, common to almost everyone with whom Kotlowitz speaks, between the possibility of hope and the undertow of hopelessness. Despite his heroin habit and his symptoms, for instance, Philip had managed to graduate from high school and enter college—no small feat in itself, and a genuine sign of the motivation to live. But he also went on to serve six years in jail on drug, armed robbery, and other charges. While he was at the halfway house, he took part in a group therapy program for ex-offenders, joined Narcotics Anonymous, and started a promising job, but this victory over trauma proved short-lived, as he began using again. Now in rehab, he lives with his mother, who’s engaged in her own struggle. Plagued by insomnia, for which her psychiatrist has prescribed sleeping pills, she fears that when she closes her eyes, rather than rest, sleep will bring just another version of the real-life nightmare that continues to spool out before her.

“You grow up in a community with abandoned homes, a jobless rate of over 25 percent, underfunded schools, and you stand outside your home, look at the city’s gleaming downtown skyline, at its prosperity, and you know your place in the world,” Kotlowitz comments. “And so you look for ways to feel like you’re someone, ways to feel like people look up to you, ways to feel like you have some standing your community.” Fear, guns, and gangs will do that.

The fate of Ramaine Hill shows what can happen when you resist those forces. After a 15-year-old gang member on a bicycle shot him in the back, Ramaine came forward as a witness against the perpetrator. He continued to hold his ground despite repeated, escalating death threats, putting in his ear buds and maintaining his routine of riding his bicycle to and from his job, and to visit his son. Whether this was bravado or a stoic acceptance of what he saw as inevitable is unclear. At 1:30 p.m. on a summer afternoon, he was gunned down on a city street, in full view of passersby. This time, no one volunteered to cooperate with the police. The no-snitch culture had won again, reinforcing the cycle of fear and despair and the belief that no one beyond those who lived there cares.

Kotlowitz portrays many who do care, though, working against the grain to begin to make a difference. Social worker and high school counselor Anita Stewart works with her colleague Crystal Smith to engage their most troubled students, visiting them at their homes to convince them to come to school, providing a quiet place in their office to sit when they have flashbacks to the multiple family and neighborhood shootings they’ve already lived through. They seek therapy for themselves to cope with the stress of the work, but they hang in, and endure, even after city budget cuts force Anita to find a new job in a different school.

It’s teachers and school officials who come to the aid of 17-year-old Marcello Sanchez, who, like others profiled in the book, could periodically explode with rage, seemingly minor incidents triggering a lifetime of dealing with constant disrespect, violation, and resentment. Afraid of more gang violence after being shot in both legs, he begged his way into a Mercy’s Home for Girls and Boys, a Catholic residence that provided him with psychotherapy and psychiatric treatment, including medication to control the anxiety stemming from being shot. He soon became a model A student, boasting he’d overcome his desire for revenge with a chest tattoo that reads, “Success is the best revenge.”

Then he snapped, getting drunk and participating in a crime spree of assault and robbery. Though deeply disappointed, his therapist and staff at Mercy came to his defense, taking him back instead of letting him go to jail, and helping him apply, and get into, DePaul University in Chicago. He seems to have come out the other side of his crisis, but he remains uncertain of where he fits in, he tells Kotlowitz, unsure of how to let his past motivate him, rather than limit him. “I feel like I’m in this alternate universe,” he concludes, one that he’s creating for himself as he climbs out of the rubble around him.

Kotlowitz has no answers for solving the many ailments that beleaguer these neighborhoods. But he’s begun by asking, listening, and learning from the lived experience of those who inhabit a reality that’s easier to ignore than explore. His empathy is both a model and a motivation for us all.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.