Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

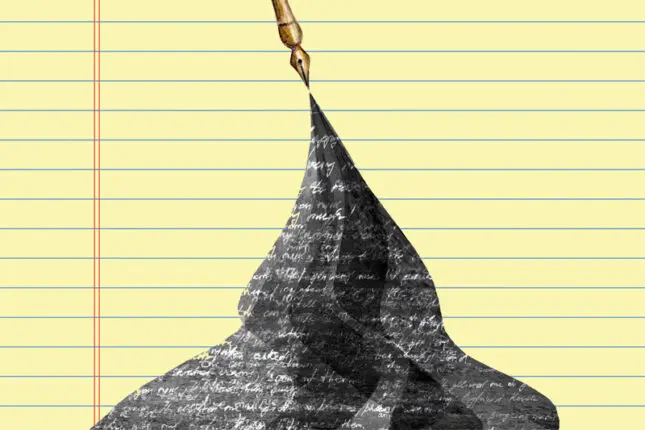

On the wood shelf beneath the bathroom medicine cabinet, a half-squeezed tube of toothpaste, cap off, waits like a silent witness: the unassuming protagonist in a story of love, frustration, and the small, ordinary things that can unravel us.

Every couple has their toothpaste tube. Sometimes it’s the shoes discarded in the hallway, the lights left on, the sigh at the wrong time. What seems trivial becomes charged with meaning. Beneath the surface of irritation lives a deeper story about fairness, respect, belonging, and the old wounds each partner has carried since childhood.

The toothpaste tube is never just a tube. It’s a portal into the ache of being unseen.

As therapists, we can miss these portals and see the toothpaste tube as just another object in a power struggle, or as a clear-cut problem to solve. In my 30 years of working as a couples therapist, trainer, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction teacher, and retreat-facilitator, there have been plenty of times when I’ve missed these portals myself. Earlier in my career, during a stressful period in my life, I found myself regularly growing impatient with clients’ problems, thinking things like, Why can’t he simply put the dishes in the sink properly? or Why can’t she be less critical of his driving? I knew my impatience was a signal that I needed to find a way back to a space of awe toward my clients and curiosity about their challenges. But how?

Then, one afternoon, bristling a little at the idea of writing session notes, I sat down and did something different. I wrote a poem. And I kept writing poems about client sessions in the days, weeks, and months that followed. Not only did poetry reconnect me to the mysterious, paradoxical nature of our work, it ended up transforming it. Over time, with clients’ permission, I began reading some of these poems aloud in session. A few people seemed surprised or laughed nervously when I first introduced the idea; reading poetry isn’t what therapists typically do. But when I used it as an intervention, something softened. The energy in the room shifted. Breathing slowed. Tears came in the pauses between words. I realized that poetry, unlike interpretation or insight, doesn’t explain, it embodies. Its rhythm and imagery speak directly to the nervous system, bypassing defenses. The client doesn’t have to think about what I mean; they feel it. In this way, poetry is like a mirror held up to the soul. It delivers recognition, not advice. It’s the difference between saying “I understand you” and transmitting the experience of being understood.

Irresolvable Conflicts

Jack and Sheila sit across from one another in my office, exhausted. I’ve been seeing them for two years and today they look sheepish and sad. Their marriage has spanned decades, but lately it feels as though they’re living side by side instead of together. Arguments arise over the smallest of things—the toothpaste tube, the list of tasks that remain incomplete, the dishes piled up in the sink—and then spiral into silence or withdrawal.

“You don’t ever listen to me!” Sheila laments. “What about me?” Jack retorts. “I asked you to introduce me to people at your work event. You ignored me.” Each feels abandoned by the very person whose support and care they long for most. Today, I wonder aloud whether the small ruptures Jack and Sheila experience with one another may be invitations rather than failures.

“They feel like failures,” Sheila says with a sigh.

“I feel like I’m failing you.” Jack, hunched in his chair, gestures in Sheila’s direction.

“I know that’s how they feel,” I murmur. “But what if they’re more like paper cuts? Even paper cuts, if you leave them untended, can get infected. In my experience, if you can notice the paper cuts, name them, and tend to them, they can open a path to deeper truth.”

Here, I turn to Imago relationship therapy, mindfulness and intentional dialogue. In the intentional dialogue, there are two roles: sender and receiver. The sender shares and the receiver engages in active listening, validates what they’ve heard, and empathizes. Not only does intentional dialogue slow the conversation, but it also provides the scaffolding that empathy needs to grow. In the silence of deep listening, irritation lessens as meaning emerges. What once seemed like nagging or withdrawal becomes a glimpse into childhood ache. Mindfulness, the practice of being present with what’s arising in the moment, gives Sheila, Jack, and I the courage to linger at the edge of what’s seemed like an irresolvable conflict.

Today, Sheila begins as the sender, and shares that the shelf in the bathroom was the last thing she made with her father, before he died. Jack leans forward, the expression on his face growing less defensive. Every time Jack leaves the toothpaste tube uncapped, she says in a trembling voice, it hurts her heart. Walking into the bathroom every morning and seeing the toothpaste leaking out onto the wood makes her angry. It’s not just that she’s asked Jack a hundred times to cap the tube—though that’s part of it. It evokes sadness about her father.

Poem as Witness

Ever since I started incorporating poetry into my note-taking—and eventually, into my work with clients—my notes have transformed into much more than just records of goals, interventions, observations, or treatment information. They include fragments of things clients have said, words that stood out, unexpected turns of phrase, evocative images, and sometimes, my own descriptions of pauses and silences that left me with unanswered questions or struck me as powerful. Poetry is the bridge between the sayable and the unsayable.

After one tense session with Sheila and Jack, I sit down at my desk and write:

He squeezes the toothpaste tube

from the middle … and leaves it there.

Every time.

No matter what I say.

I let myself experience Sheila’s frustration, and the deep pathos it carried. It isn’t just leaky toothpaste that upsets her. It’s the weight of her unspoken plea. See me. Hear me. Care enough to notice my requests and respond to them.

At our next session, I ask permission to share what I’ve written, and Sheila and Jack express openness to listening. When I read the lines, Sheila weeps. She says I’ve given her irritation a shape and a voice that affirms its validity. But by capturing it in poetry, I’ve also highlighted beauty in a space where no one has seen beauty before, not even her. Seeing her response, Jack’s facial expression softens. What he’s dismissed as nagging and absorbed as criticism becomes a window into Sheila’s longing.

Why does this move them so deeply? It’s not because what I’ve written is somehow flawless, or worthy of a poetry award. The poetry that heals isn’t found in perfect lines or clever turns of phrase. It lives in the therapist’s capacity to be moved—to find meaning in what might otherwise be missed, and to offer that back with tenderness. This is poetry! Its power lies in how it shifts the register of communication, and all therapists can access this, regardless of their skills as a poet. What matters is the spark of genius that lives in your own way of seeing, listening, and daring to name what’s real.

Poetry doesn’t argue or persuade, it illuminates. When I share a poem, I’m not telling clients what to think; I’m showing them what love, grief, or misunderstanding feels like. The couple senses I’ve metabolized their experience, not just analyzed it. They feel witnessed, not studied. Poetry touches the ineffable. It gives language to what otherwise trembles just beyond words. That difference—the movement from cognition to resonance—can support rapid transformation.

As we continue our work and linger more often in the vast, rich space beneath their arguments, more layers emerge. What seemed petty isn’t petty at all. It’s sacred. Once we learn that the half-squeezed, capless toothpaste tube is resting on the last project Sheila and her father, with whom she had a complicated relationship, completed as a team, it takes on new meaning. It becomes clear that the tube is a visual reminder of her father’s absence. And the shelf isn’t just a shelf. It’s a fragile remnant of their connection. A careless smear of toothpaste feels like an act of desecration.

That shelf

the one beneath the cabinet,

now stained with minty smears

was the last thing my father gave me

before he died.

Jack, in turn, begins recalling and sharing more about his childhood. He tells Sheila about how it had felt to be the only boy—the youngest of five children—in a family of women. In their small New York City apartment, there wasn’t enough space for him to have his own room, so the living room couch doubled as his bed. His mother took her frustrations out on him, calling him thoughtless and inconsiderate when he took too much time in the bathroom with a line of girls waiting to get in. The tube, we learn, has become a battleground where grief meets shame—where two childhoods collide in the morning light. And it leads to more poetry later, as I’m recalling what touched or moved me about our latest session.

His mother yelled at him

to hurry up,

to get out of the bathroom.

Four sisters.

Nowhere to go.

No mirror that belonged to him.

When I share these lines with Jack, his face lights up with the rare joy of being seen and understood. His posture changes. It becomes less guarded, more open. For a moment, he’s not defending himself but receiving himself through another’s eyes. Sheila reaches toward him, takes his hand, and slides close on the couch.

“It’s the first time I’ve really heard your story,” she whispers. “I always thought you were just careless. I never knew what it cost you to grow up that way.”

Jack nods. “I didn’t realize how much of that I was carrying into us.”

In that moment irritation softens into empathy. The toothpaste is no longer just a tube, or the focus of a fight—it becomes a window. Through it, each partner glimpses the child in the other, and something new and tender begins to grow.

Poetry carries my work with Jack and Sheila forward long after the 50 minutes of our session. They begin to read the lines together at home, and report back to me that sometimes, it helps them laugh at the absurdity of their fights. At other times, it becomes a catalyst for tears as they uncover tenderness they hadn’t known was there. They even begin to make edits, rewrite my lines, and add their own lines. They transform the poem into a crowdsourced creation, something that’s not mine, but ours. Here are some lines Sheila and Jack wrote together:

We both carried old stories

into the quiet war

of the morning routine.

But here………

in the sacred space

of intentional listening,

where no one interrupts,

where empathy is the only rule:

we saw the child in each other.

When Sheila reads this, I feel wonder and joy expanding my chest, as if the room itself has widened. I sense a quiet recognition moving between them, an invisible thread tying past to present, wound to wound, heart to heart. Jack smiles. Toothpaste has become memory. Irritation has transformed into longing. And love—real love—emerges for all of us to appreciate. It exists not in the fixing, but in the seeing.

A Gift We Give Ourselves

Poetry hasn’t just helped my clients. It’s saved me. When I wrote that first poetry fragment long ago, I was weary and stretched thin, trying to hold the weight of others’ sorrows while carrying my own.

Burnout is rampant in our field. Therapists are asked to sit in silence when we’d rather flee, to hold pain when our own hearts are tired. Clients can feel when the light has dimmed inside us. For me, poetry has been a lifeline. Writing poems like The Toothpaste Tube prevents numbness. It transforms repetition into discovery. It invites humor, play, and beauty back into the consulting room. It nourishes me as much as my clients.

Self-care, I’ve learned, isn’t just yoga or rest. It’s creativity. It’s giving ourselves permission to make art from what we witness—even sorrow, frustration, and pain. It’s finding metaphors and images and paradoxes that help us laugh amidst grief, when we can. It’s finding creative methods that help us see the ordinary as luminous.

A lot of things can get in the way of therapists accessing our poetic sensibility, particularly as it relates to working with clients. We may compartmentalize work and art as separate activities. We may believe that all poetry has to be “good,” or that we have no right to create poetry out of the things our clients bring to sessions, because it’s a breach of privacy. Or we may simply be too tired, too hurried, or too overwhelmed to pause and relish beauty amid pain.

But you don’t have to channel Rumi or Mary Oliver to write poetry. A few raw, imperfect lines can capture the emotional essence of a session. The power isn’t in polish, but in presence. When you share poetry with your clients with their consent, it becomes a collaborative tool. But even when you don’t, it can serve as a private reflection that keeps therapists connected to the humanity in their work. It’s never about exposing clients—it’s about honoring their stories.

In fact, our work is already a form of art, as well as science. We can remember that every dialogue, every silence, every gesture between therapist and client, is inherently creative. Poetry isn’t something we “add on.” It’s already present in pauses, metaphors, and fragments of story that shimmer in the room. The invitation is to notice, honor, and—if we choose—shape what we witness into language that nourishes both our clients and ourselves.

Here are some steps you can take as a therapist to access poetry in your work—whether or not you choose to use it as an intervention with your clients.

Shift your lens by noticing what’s beautiful, charged, alive. Listen with a poet’s ear. Pay attention to the “little” things: phrases, gestures, images that shimmer with energy.

Circle what stands out. Make note of the words, actions, or moments that felt most alive in your session. Was there a particularly loaded pause? A silence that spoke volumes? A tremor or shiver that passed through a client at a particularly meaningful moment?

Use a prompt to give yourself permission. Ask yourself, “If this session were a poem, what would its first line be?” or “What truth is hiding beneath the words?”

Write a fragment. Follow the emotional thread, not the storyline. Let it be short, messy, unfinished.

Shape with care. Refine the lines you write so they reflect the essence of what you experienced. Don’t get hung up on facts or try to explain everything. Leave room for mystery.

Share a few lines with your clients (optional). If it feels appropriate, and always with your clients’ consent, bring the poem into a session in a way that keeps the focus on the work. Invite your clients to add, edit, or simply sit with it. They’ll often feel touched that you think of them when you’re not together, and honored to see their truth reflected in art.

Let the poetry you create nourish you. Even if you never share the post-session poetry, this practice transforms notetaking from a chore into an act of devotion. It keeps you connected to the work in a way that’s creative and vibrant, which impacts how your clients experience you in session.

Making Room

Jack and Sheila haven’t resolved every fight. They still squeeze the toothpaste tube differently. Sometimes Jack forgets to put the cap on. But they no longer treat the tube as the enemy. Now, it’s a reminder of what they’re both carrying into the relationship, and of how they’ve learned to see each other more clearly. After many rewrites, collaborative edits, spontaneous readings, and inspired lines, Jack and Sheila presented me with this new ending to their poem.

We still squeeze the tube differently.

But now, when I see it lying there,

I think of his boyhood ache.

He thinks of my father’s hands.

And sometimes

we laugh.

Because love, eventually,

makes room for everything.

Life is poetry. In its ordinariness—shoes in the hallway, toothpaste tubes, clothes on the floor, eye rolls, sighs—we find the raw material for healing. When we dare to slow down, notice, write, and share, we allow beauty into the dynamic. This is why poetry matters in therapy. It oxygenates the connective tissue of relationships. It allows couples to approach each other not only in conflict, but in creativity. And it reminds us that the ordinary is never just ordinary. It speaks to the ineffable.

Poetry isn’t a gimmick. It’s a mirror, a bridge, a sacred offering.

Creativity isn’t an accessory to therapy. It’s one of its secret engines. For me, writing poems and essays is as much an offering to my clients as it is a way for me to stay alive and connected in my work. It invites humor and play into a space where rigidity could take over. It brings beauty into rooms that sometimes feel emptied by loss. It lets me remember that what we’re doing together isn’t mechanical but relational, human, and full of mystery.

For couples, it can turn frustration into tenderness.

For therapists, it can transform burnout into renewal.

For all of us, it’s a reminder that love, eventually, makes room for everything.

Jayne Gumpel

Jayne Gumpel, LCSW, is a psychotherapist, trainer, and teacher with 30 years of experience working with couples, individuals, and groups in New York City and Woodstock, NY.