Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

Six autumns ago, I entered the hushed quiet of the Sistine Chapel and gazed up at The Creation of Adam, Michelangelo’s magnificent fresco. I was mesmerized by the image of God reaching out to touch Adam, closing that final, tiny gap between their fingertips to ignite the spark of life. Lifting my eyes, I was surprised to feel a vibration deep inside my chest, a visceral ache, which I realized was my own longing for touch.

Looking back, I’m not surprised by the intensity of my response. It’s only natural. Touch is sometimes described as “the mother of all senses,” the first to develop in the embryo and the first to offer an experience of human connection. Bonding begins even before birth, when a mother places a hand over her stomach and the baby responds by reaching out to touch the walls of the uterus.

The need for safe touch continues throughout our lives. A recent study of 509 adults by Kory Floyd, professor of communications at the University of Arizona, found that people who suffered what he called “skin hunger” were more likely to experience loneliness, depression, anxiety, and immune disorders. Especially in this culture, relatively few of us get as much safe touch as we need. The United States may be among the most touch-averse countries in the world.

A now-classic study by psychologist Sidney Jourard observed friends from various regions of the world sitting together in a café. During the space of an hour-long conversation, French friends affectionately touched each other 110 times, while Puerto Ricans made physical contact an astounding three times per minute, for a total of 180 times. Now, get ready: in the United States, friends touched each other exactly twice. Only the buttoned-up Brits did worse—their touch score was zero.

Certainly, our touch-avoidant culture plays out in the therapy room. Relatively few clinicians touch their clients in any kind of sustained, therapeutic way. Outside of therapists who explicitly use body work in models such as Somatic Experiencing and Hakomi, most clinicians tend to avoid, or at least scrupulously limit, physical contact with clients. Such vigilance is understandable. Using touch in therapy is a complex issue, fraught with legitimate concerns about boundary breaches that could include anything from an unasked-for shoulder squeeze to overt sexual contact.

For clients who’ve suffered harmful touch, the experience of safe, nonsexual physical contact may feel foreign and frightening. For many clinicians, touching a client may seem not only unethical, but loaded with potential for lawsuits and damage to their professional reputations. As a result, the notion of a therapist making a tactile connection with a client can feel dangerous for both parties. Even between a female therapist and a female client, touch rarely goes further than a hug at the start or end of a session. Seldom is it used as a fundamental, consciously chosen element of treatment.

I believe we need to revisit and revise this taboo. For five years now, I’ve been using touch in my own practice, guided by the Polyvagal Theory of psychologist and neuroscientist Stephen Porges. In my experience, physical contact can be a profoundly healing experience when approached with consciousness, sensitivity, respect, and mutual agreement. A clinician’s judicious use of touch can restore safety and stability to an agitated nervous system, allowing an individual to connect with others with a new openness, and begin to change his or her life story from a powerless narrative to a nourishing one.

So, what’s this thing called Polyvagal Theory, and how can it help us understand and guide the healing potential of therapeutic touch? To address this question, I’ll need to use a few neuro-nerd terms, so bear with me. My aim is to delve into the particular body states, social cues, and interpersonal responses that can help us feel lovingly held in another’s mind and heart—or can leave us feeling alone in the world.

A Polyvagal Primer

The fundamental premise of Polyvagal Theory is that human beings need safety, and our biology is fiercely devoted to keeping us out of harm’s way. As most therapists know, the body’s rapid-response survival system is orchestrated by our autonomic nervous system (ANS). To briefly review, the ANS operates two branches: the sympathetic and the parasympathetic. The sympathetic branch mobilizes us to defend against danger via the fight-or-flight response. The somewhat less understood parasympathetic branch is typically viewed as a unitary system that helps us lower our defenses and regain a state of calm.

But, as they say, it’s a bit more complicated than that. The parasympathetic system is made up of the vagus nerve, which starts at the base of the skull and winds its way down the body to the abdomen. It branches into two major pathways, each responsible for a distinct neurophysiological state. One pathway, known as the ventral vagal, responds to cues of safety and supports a sense of centeredness and readiness for social engagement. By contrast, the dorsal vagal pathway responds to cues of life-threat, causing us to shut down, become numb, and disconnect from others. A client who dissociates has found refuge in a dorsal vagal state.

Importantly, these cues for safety and danger operate beneath our awareness. The three elements of our autonomic nervous system—ventral, sympathetic, and dorsal—act as our largely subconscious surveillance system, working in the background to read subtle signals of safety or threat. Porges coined the term neuroception to describe the way our ANS scans for cues of safety and danger without any assistance from our thinking brains. For example, if you enter a loud, crowded party and see strangers huddled together, laughing, you may unconsciously pick up cues of rejection. In a micromoment, your sympathetic nervous system leaps into action, signaling you to turn around and leave the party posthaste, or perhaps head straight to the buffet and fill a plate.

Just then, you notice one of the guests breaking away from the crowd and walking toward you. She extends her hand and introduces herself, her face open and welcoming. Almost instantly, your breathing slows, your heart rate goes down, and your body relaxes into the experience of Ah, I’m safe now. Your ANS has just guided you from a sympathetic state to a ventral vagal one, permitting what Porges calls your social engagement system to come fully online. You’re now calm, ready to connect—and maybe initiate a new conversation.

Polyvagal-Informed Therapy

From a polyvagal perspective, a key goal of therapy is to help the client find ways to move out of a dysregulated state—either a numbed-out “dorsal vagal” state or a hyperaroused “sympathetic” one—and return to “ventral vagal,” the biological seat of safety and connectedness. And because we can change our dominant life story only from a place of ventral vagal, it’s crucial for both therapist and client to be able to accurately identify the state of their own nervous systems at any point in time—both in the therapy session and out in the wider world. Only when individuals are able to recognize their location on the polyvagal map can they begin the journey back to calm and connection.

Notice that I said both therapist and client must become aware of their autonomic states. That’s because emotional healing can only take place when clinician and client establish a trusting nervous-system-to-nervous-system connection. Subconsciously, clients are continually picking up subtle cues from their therapist via tone of voice, eye contact, body postures, and facial expressions, from a slightly wrinkled brow to a particular movement of a hand. Throughout the session, clients are constantly reacting to these signals with sympathetic activation, dorsal shutdown, or ventral openness and trust. So from a polyvagal perspective, healing client–therapist relationships require therapists to know their own ANS and learn how to regulate it in the moment, in the midst of any session.

Getting to Know Your Nervous System

Today, most people come into therapy with a general understanding of the concept of “body-mind,” the notion that their physical and emotional selves work in concert. But I’ve found that relatively few people understand the precise ways in which the body creates emotional experience, in turn prompting individuals to behave in predictable ways that create and perpetuate a story about themselves and the world they inhabit. That’s why, well before bringing touch into the equation, I help clients create a clear map of their own autonomic nervous systems, so they become aware of their patterns of response to ease and distress.

Following some brief psychoeducation about the three parts of the ANS, I ask my clients to create a personal profile of their own. I suggest that they imagine their nervous system as a ladder, with ventral vagal at the top, sympathetic in the middle, and dorsal vagal at the bottom. (Here, I provide a worksheet with an image of a ladder.) Clients start by writing down their typical feelings and behaviors when they’re in a sympathetic state, often using words and phrases like out of control, angry, confrontational, fearful, and desperately seeking. They do the same for their experiences of being in dorsal vagal, which may include silent, out of focus, numb, hopeless, helpless, shut down, and feeling abandoned and unwanted. Finally, they recall times of being firmly planted at the top of the ladder—the ventral vagal zone. These typically include such descriptors as openhearted, engaged, curious, and playful.

I then ask my clients to complete their personal profiles by finishing two sentences for each state: “I am…” and “The world is…” Most clients are astonished by the dramatic difference in their core narratives, depending on the zone they inhabit. In a ventral state, people typically characterize their story as something like “I belong” and “the world is welcoming and filled with opportunity.” In sympathetic, they may say, “I feel crazy, panicked. I’m trapped in a world that’s unfriendly and scary.” When in dorsal, the response is something like: “I’m invisible, unlovable, lost, alone. The world is cold and empty.”

Now clients have both a mental picture and a language for their “ladder” of ANS activation at any given moment. Importantly, client and therapist now share this language, so that during a session they have a useful shorthand for noticing, naming, and addressing these ever-changing states of arousal. Over time, we want to help clients shift their default ANS setting from a place of danger and distrust to a state of openhearted safety.

Yet before going further, I want to emphasize that the polyvagal perspective is by no means a replacement for any particular model of therapy. Rather, it’s a way of looking at the nervous system, one that can inform and deepen any clinical approach. I think of it as a kind of moment-to-moment awareness of the ongoing biological reactions of self and others that deeply influence the quality of the therapist–client relationship—and ultimately, a client’s fundamental sense of safety in the world. It’s an element of mindfulness; ideally, it’s a tool for healing.

A Polyvagal Approach to Touch

So from a polyvagal perspective, why use touch in therapy? Recall that earlier on, we introduced the concept of neuroception, which refers to the ANS’s perpetual, vigilant scanning of the environment that allows us to pick up subtle cues of safety or danger while interacting with any particular person or environment. A client detects these cues in a therapy session as readily as anywhere else. For example, if the clinician briefly drops eye contact, exhales too vigorously, or thins her lips just a bit, the client may instantly shift from ventral into sympathetic (fight or flight) or dorsal (the collapse response), her body-mind instantly issuing a warning that the therapist has become untrustworthy and dangerous.

To help guide the client back to a safe ventral state, therapists need to be regulated themselves and communicate signals of caring and connection. Words mean relatively little here. Instead, the clinician must send nonverbal cues—tone of voice, body position, softness of gaze, possibly a gentle touch—to restore connection and help the client’s nervous system return to safety.

I’ve found that of all these nonverbal cues of safety, touch can be especially effective, because it’s a direct and palpable experience of support. As Porges has said, feeling “safe in the arms of another” is among the most powerful routes to reestablishing an internal sense of well-being. Of course, using physical contact in the therapy room is an extremely delicate endeavor, since depending on a client’s history, touch may be among the most dangerous cues he or she can receive. So in this realm, I move slowly and carefully, making sure that the client is always in charge of the process.

I gently introduce touch from my first meeting with clients, via a handshake at both the start and close of the session. But I don’t explicitly introduce the topic of touch until clients have completed their initial personal profile map and we’ve discussed their nonverbal cues for safety and danger. At some point, I ask if they’d be willing to talk about touch, and how they’ve experienced it in the past. Have they had any intrusive, harmful experiences? Any nurturing ones? Right now in their life, what kinds of touch are definitely not wanted, and what kinds might be okay?

To facilitate this part of the conversation, I talk about the kinds of physical contact that may evoke ventral vagal warmth, sympathetic distress, or dorsal vagal numbing, respectively. This “menu” includes examples of types of supportive touch I could offer, including (but not limited to) touching a client’s hand, touching palm to palm, placing my hand on the upper middle of a client’s back, and putting my hand on any of the following—a client’s knee, shoulder, upper arm, lower arm, or elbow. I explicitly explore the meaning of a hug, since a hug is a common request from clients and not always a welcome form of contact. We experiment with various kinds of touch from the menu to find out which ones they feel comfortable with and which they find dysregulating, and, using the ANS ladder as our guide, we create a touch map.

Based on this information, we make an explicit touch agreement, a written statement specifying which modes of touch feel nourishing, which ones we might carefully continue to experiment with, and which ones bring too great of a dysregulated ANS response to consider using in therapy. We write the agreement together, making sure the language clearly states what we’ve learned from the touch map. And with this agreement, we now have a guide to bringing touch into therapy.

The Delicate Dance of Touch

When Sarah came into my office for her first appointment, she sat down heavily and looked down at my rug. The 38-year-old history professor had already seen two other clinicians, both of whom she felt had misunderstood her frequent silences as resistance to the therapy process. “One kept urging me to make eye contact, while the other told me, kind of judgmentally, that I seemed disengaged.” She shrugged. “I said that I felt kind of empty; I didn’t know how else to explain it,” she said. “Maybe I’m beyond help. I don’t know.”

We talked some more about Sarah’s chronic experience of emptiness. When she eventually trailed off, I asked a few clarifying questions and shared with her a bit about the polyvagal perspective. She seemed interested, so I offered her a blank ladder map to fill out. At the top of the ladder—the ventral vagal zone—she couldn’t identify many personal experiences, but she did say she occasionally felt what she called a “sweetness,” when “the world seems friendly.” In the middle, which signified the sympathetic nervous system, Sarah identified reactions of “ready to run” and out-of-control eating. “I can eat a whole box of Oreos in one sitting,” she admitted. “It calms me, at least temporarily. Otherwise, I’m kind of swirling and the world is all disorganized.”

As she looked at the bottom of the ladder—the zoned-out dorsal vagal state—she began to nod in recognition. “This is how I usually feel,” she said. “My black hole.” She said that from that place she could function well enough with her students and friends, “but inside, I’m locked away,” and “the world is an empty place.” She then revealed that as a preteen, she’d been repeatedly physically and sexually abused by a close family friend.

As I listened, I used my body language of sitting quietly in my chair with a soft gaze and a slight tilt of my head to let her know that I was a safe person. Then I suggested to Sarah that her disappearance into a “black hole” was actually the way that her nervous system had been trying to protect her from harm. “You may have felt like a helpless victim, but you were actually a determined survivor,” I told her. It made sense that her intense and enduring dysregulation had made it impossible for her to show up and stay present enough to engage in therapy—or in her daily life.

Once Sarah had identified and described her nervous-system states on her personal profile ladder, I introduced the topic of touch. She told me that the moment someone tried to touch her, however gently or supportively, she’d feel threatened. Yet she longed for affectionate contact. “I see other people holding hands and I want that,” she said. “When I see friends hugging each other, my heart kind of squeezes.” Sarah’s voice had become a little wobbly, but her expression remained stoic. “I know that touch is for other people, not for someone as damaged as me.”

“I hear you,” I said softly, nodding. “And if you’re willing, we could investigate that belief a bit.” I asked her if she’d be interested in experimenting with a touch menu that could help her notice and name the kinds of physical contact that evoked either “sweetness,” “disorganization,” or “black hole.” As Sarah considered this, I let her feel my own regulated state, my nervous system sending her cues that it was safe to take this next step. Breathing with slow inhalations and exhalations, looking at her with a soft but focused gaze, I telegraphed I was calm and present and not making a demand. I settled into my chair, letting my relaxed body signal safety. I waited silently for Sarah to respond, knowing that sitting safely in silence sends a powerful message of regulation as well.

“Where are you on your ladder map right now?” I asked, checking in after a while.

“I’m feeling the pull of my black hole,” she said. “But your face is keeping me from disappearing. When you look at me, I feel like you see me and will stay with me. I don’t feel judged.”

“Take that in,” I said softly. “See what message my nervous system is sending to yours. See if you can feel a bit of your place of ‘sweetness’ as I hold you in my ventral vagal energy.”

Sarah and I were now moving into connection, nervous system to nervous system, an essential prerequisite for therapeutic healing. Still, she hesitated. “Touch is scary,” she murmured. “People get hurt when they touch.” I nodded, looking at her with soft eyes. “I know it’s really different to think that touch might be safe, might be nourishing—that some kinds of touch might actually live in your state of ‘sweetness’ and some, even it’s just a hand on your hand, might help you get there.”

Sarah took a deep breath. “Yeah. Okay, then. Let’s try it.”

Lending a Hand

Over the course of the next several sessions, we made our way through the touch menu, tracking both small and large shifts in Sarah’s nervous system as we experimented with a range of potentially healing touches. She was surprised the first time we found a touch that she felt belonged in “sweetness.” This was the palm-to-palm touch, in which we held our hands out of in front of us, and Sarah’s hands moved slowly toward mine until they found connection. I asked, “Where is your nervous system taking you right now?”

“It feels okay,” Sarah said, her tone uncertain. “Maybe good. I don’t know how to describe it. I guess, unfamiliar?”

I asked, “Does it carry ‘black hole’ energy? Maybe confusion? A bit of the flavor of sweetness?”

We stayed palm-to-palm for several moments, and then Sarah whispered, “I think I’m finding the top of my ladder.”

As we continued to scan the menu, Sarah found other touches that evoked her ventral vagal state, including placing my hand on the middle of her back as well as sitting side by side, our upper arms touching. We tried out other touches, finding the moment our feet touched or an offer to hold her hand activated her sympathetic system. Still others, a touch to her knee or lower arm, triggered collapse. We carefully explored the touch menu, talking about each option before trying it and moving slowly to bring each touch into full expression. This way, we could track the first stirring of dysregulation, stop, and consider the next step. Sometimes Sarah would know just where to place the touch and sometimes she wanted to experiment a bit more.

Once we’d experimented with various kinds of touches on the menu, Sarah and I made a touch agreement, which identified the kinds of physical contact she was willing to receive from me at points when it might be helpful as we worked, and what kinds felt unsafe and off-limits.

Staying Connected: It Takes Two

A couple weeks later, Sarah came into our session looking pale and tense. As soon as she sank into the couch, she described an incident that had taken place a few days before, when she’d read an article in the local paper describing a charity event named for the family friend who’d abused her. It had sucked her back into the black hole. My nervous system picked up her frozen, locked-away place. As she talked, the only parts of her body that moved were her hands, which she twisted almost imperceptibly in her lap.

Usually, in such moments with Sarah, I could meet her in her state of dorsal collapse and use my ventral vagal energy to help her find her way back to “sweetness.” But not this time. Without warning, I felt my muscles tense, and the exasperated thought formed, Here we go again. That reaction was followed by an unvoiced command, “Just stop it, Sarah!” I felt an impulse to reach over and grab her to keep her from falling any further into the black hole.

Fortunately, at that moment, I noticed my intense reaction, along with the frustration and anger that fueled it. I was able to name it as a “sympathetic storm,” and I knew that Sarah’s neuroception was taking it all in whether she was aware of it or not. “Let me take a moment,” I told Sarah. I acknowledged to myself that my body had a reason for spiraling into a survival response. Then I let out a deep breath, a sigh, that’s my dependable resource for reconnecting with my ventral vagal anchor. (Sighing, a long slow, audible exhalation, is an everyday experience that’s a body and mind resetter. We spontaneously sigh many times an hour as our ANS resets and regulates. And we can use intentional sighing to bring that regulation in when needed. I teach this to all my clients, so I knew that if Sarah noticed my sigh, she’d understand I was coming back to regulation.)

As I returned to a place of calm, I knew that I needed to acknowledge to Sarah what had just happened. “I just had a moment of mobilization,” I told her. “Did you feel that on your end?”

When she nodded, I said, “I want you to know that it wasn’t about you—it was my ANS responding to something in my own experience. I’m right here with you now, holding you in warmth and caring.” Later, I’d talk with a colleague about why I’d gotten so mobilized, but now was the time to reestablish connection with my client. So I sat down next to Sarah on the couch and placed one hand gently on the middle of her back. “My ventral vagal system is reaching out to yours,” I said, my voice low and warm. “I’m sending my own energy of ‘sweetness’ toward you. Can you feel that?” Sarah leaned into me just a bit. I kept my hand on her back, our arms lightly touching as we sat side by side. “I’m right here,” I said again.

Sarah began to cry. We sat there for a while, not speaking. Slowly, her tears subsided and her breathing deepened. When she sighed, I noticed that out loud. “That was a lovely sigh,” I told her. “It’s a sign that your nervous system is beginning to come back into regulation.” After another few moments of silence, I said, “Feel the way our bodies are just slightly touching. Your system is remembering that it knows the way back to sweetness. Let’s see if we can find our way together.”

As Sarah slowly made her way from collapse back into connection, we continued to sit together silently for a few minutes, my hand still on her back for a bit and then us simply sitting side by side. Together, we savored the neuroception of safety that touch had created. Next, we brought explicit awareness to the experience, talking about the pathway back to her ventral vagal state.

Sarah was amazed that touch had actually made a positive difference. “I’m usually locked away in that black hole for a long time,” she said. “My friends try to talk to me when I’m in that place, and I know they’re offering comfort, but their words don’t feel strong enough to hold me.” She paused, reflecting. “Your touching me was different. Your hand felt strong and gentle at the same time. My body felt . . . protected, somehow. I could feel you at the top of the ladder, kind of reaching for me. And I remembered that I have a place there, too.”

As we continued our work together over many months, Sarah created a number of resources for redirecting her nervous system when she was outside the therapy room. Among them were guided imagery apps, music, journaling, and breathwork. But our use of touch continued to be an immediate and powerful way to interrupt the pull toward the black hole and to deepen into the energy of sweetness. Crucially, our work also enabled Sarah to shift her core narrative about touch from an inevitably harmful experience to a potentially healing one.

“I realize that my nervous system can respond like a normal person’s,” she said. “I’m not broken.” She paused, and then added, “Touch might not always be safe, but now I feel it’s not automatically dangerous.” Sarah’s new narrative was creating a healthy upward spiral: the more she operated from this revised story, the more easily her nervous system could shift from default dorsal to something closer to default ventral. And the more flexible her autonomic nervous system became, the more robust was her new, more empowering story.

Other Touch

Direct touch between client and therapist is only one way to generate the healing potential of physical contact. I’ve found that mirroring a client’s self-touch can be another powerful approach. For some clients, self-touch paired with mirroring serves as a safe and gradual pathway toward direct client–therapist touch. For other clients, this process may be the only form of touch they want to bring into therapy.

When clients are feeling something deeply, they often spontaneously place a hand over their heart. I’ll echo this gesture, placing my hand on my own heart so they can see and feel that they’re not alone in the midst of an intense experience. Deep in their bodies, they get that I get it. Usually, I pause and bring attention to this moment, inviting clients to viscerally experience our coattunement and notice their ANS response.

At other times, I explicitly invite coregulation via mirroring. “Let’s both try placing one hand on our heart and the other on the side of our face,” I say, “and remember the power of our nervous system to keep us in safety and connection.” These remembered experiences of self-touch and mirroring give clients another tool to use outside the therapy office. In their daily lives, whenever their nervous system begins to spark or crash (and of course it will), they have a way to begin to soothe themselves.

So in addition to the therapist touch menu, I present clients with a self-touch/mirrored-touch menu, from which they can choose the forms of contact that work best for them. Other than the hand over the heart, I offer the possibilities of hands in prayer (or namaste position), fingers interlaced, a hand cradling the back of the head, and many others. Then we construct a ladder map, identifying which self-touches and mirrored touches hold them in a safe ventral place, which ones pull them into a sympathetic state, and which ones plunge them into the dorsal zone.

At some point, many clients ask if they can bring an important person in their lives into a session. Often this is a committed partner, but it could be a sibling, a parent, or a close friend who has the potential and desire to be a safe and supportive coregulator. I’m always delighted to include them, because they can become a rich resource for mutual healing beyond the therapy hour—and ideally, for years to come.

Beginning with a brief overview of the nervous-system hierarchy, I invite the client to engage in a conversation about touch with their support person, asking them both to identify and share the nonverbal, interpersonal cues that can move them up—or down—the ladder. These neuroceptions include touch as well as other nonverbal cues. As they get to know each other’s ANS points of activation, they learn how to send cues of safety to each other, and they develop concrete ways to help each other get back to a ventral vagal state when they, like all of us, inevitably slip out of it. Perhaps it goes without saying that this kind of work can wield an enormously positive impact on the relationship itself, often spurring new levels of intimacy and skillful support.

Polyvagal-informed therapy, vagal ventral, dorsal vagal, neuroception. Some people find the terms associated with this therapeutic approach ungainly and complicated. But I actually find the tongue-twisting terminology kind of ironic, because in my experience, the polyvagal perspective is pretty straightforward. At heart, it’s a particular way of understanding and using human connection to heal.

Biology, it turns out, is the prime mover of our relationship stories, before emotion ever gets involved. With a more comprehensive understanding of the body’s role in creating connection and disconnection—and a precise language to describe it—we have a better map to help guide our clients back to safety.

Human touch is one reliable route home. There are others, of course, some of which have yet to be discovered. We’re in new territory, and we’re still charting it. As I see it, all of us therapists are explorers in search of the land of ventral vagal. Social engagement, equilibrium, a place of sweetness—whatever you want to call it, that’s where we want to go.

PHOTO © GETTYIMAGES/TRACK5

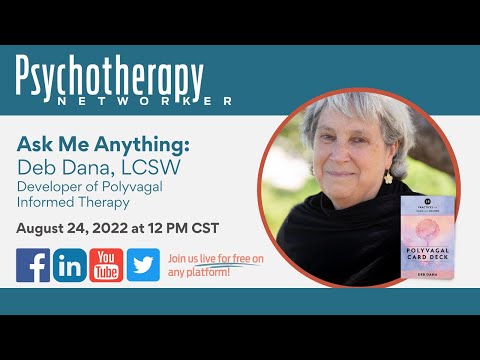

Deb Dana

Deb Dana, LCSW is a clinician and consultant specializing in working with complex trauma. She’s a consultant to the Traumatic Stress Research Consortium in the Kinsey Institute and clinical advisor to Khiron Clinics. She developed the Rhythm of Regulation Clinical Training Series and lectures internationally on ways Polyvagal Theory informs work with trauma survivors. Deb is the author of The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy: Engaging the Rhythm of Regulation, Polyvagal Exercises for Safety and Connection: 50 Client-Centered Practices, co-editor with Stephen Porges of Clinical Applications of the Polyvagal Theory: The Emergence of Polyvagal-Informed Therapies, and creator of the Polyvagal Flip Chart. rhythmofregulation.com