Right now, we’re all subjects of what’s arguably the most widespread, fastest-paced, unplanned experiment on human psychology ever conducted in history. The research question is: what happens to the human brain when, within a few short decades, it’s introduced—in fact, saturated in—a radically new, instantaneous communications technology that links up billions of people and expands access to untold quantities of information over the entire globe? Does this revolution in technology genuinely enhance human connection or just the opposite? Does it make us smarter in some ways, dumber in others?

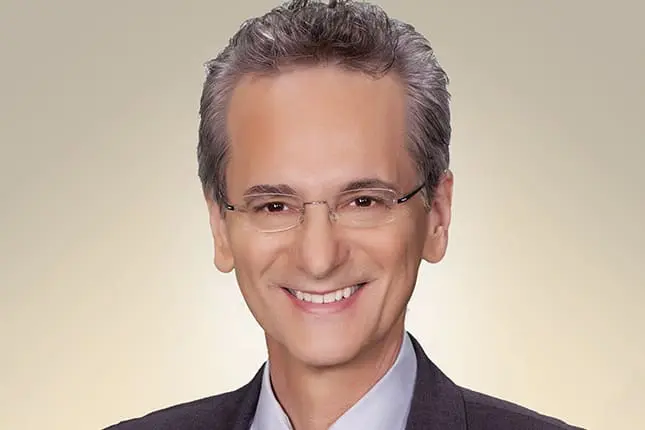

Gary Small, a UCLA psychiatrist, neuroscientist, expert on memory and aging, and author, with his wife Gigi Vorgan, of iBrain: Surviving the Technological Alteration of the Modern Mind, is on the cutting edge of research about how our digital world is transforming the human brain. In this interview, he discusses how technology is changing our minds and suggests when therapists should respond to clients whose relationship with technology has become unbalanced.

—–

RH: How did you get started looking at how technology influences the brain?

SMALL: My field is geriatric psychiatry, and I’ve done a lot of research over many years on brain function, brain structure, brain aging, and mood and memory. As a tech geek myself, I was drawn to the question of how all these new technologies are affecting the brain. At some point, the question that most interested me changed from “How can we use technology to measure the brain as it ages” to “Let’s find out what this other technology is doing to the brain at every age.”

RH: Speaking of all ages, you were recently quoted in a New York Times article about the impact of easy-to-use tablet computers on toddlers. What’s your take: good or bad?

SMALL: Basically, we don’t know, but there’s a growing concern because a lot of parents are increasingly using tablets and other digital technology as pacifiers. Is that going to inhibit children’s development of language skills? Some studies suggest that too much screen time could contribute to AD/HD symptoms and lower performance in school, but there’s also a lot of individual variation: some children are more sensitive than others to large amounts of screen time.

RH: Speaking of the impact of technology, how about adults? Is it true that my cell phone is destroying my capacity to remember phone numbers?

SMALL: It’s not destroying it, but basically what you’re describing is a nonissue. The reality is that you don’t need your brain to remember phone numbers in today’s world. For that and many other things, you can use your digital devices to augment your biological memory—for remembering names and faces, and for focusing your attention when you’re having a conversation. In fact, your brain power is better spent learning the apps to use so you can take advantage of the computer as an extension of your biological brain.

RH: So don’t go overboard in seeing computers as having a damaging effect on our cognitive capacities?

SMALL: Exactly. [Phone rings in background.] Please excuse me for a moment [On hold. Four minutes of Muzak.] Hi. I’m sorry about that. I’m afraid I’ve got a fundraiser right now that needs a little bit of my attention. I don’t usually take calls like this, but this underlines part of the whole problem with technology.

What I was just doing in taking that call is called continuous partial attention—scanning the environment for something that’s more imminent than what’s going on. It’s actually a stressful thing that’s not good for our brains or for our relationships. In fact, right now I feel a little guilty that I wasn’t paying full attention to you.

RH: No harm done! Actually, I’m so used to being interrupted by technology that I hardly even notice it.

SMALL: This is one of the issues that people frequently experience in face-to-face conversations these days. They’re talking with someone who won’t look at them because the other person is texting at the same time. So they think, “Eh? Does this person really care about me?” This is having more and more of an impact on the level of social connection people feel.

RH: How’s the influence of technology different from any other factors on social connection?

SMALL: We don’t exactly know, but the principle is this: your brain is sensitive to mental stimuli from moment to moment. If you spend a lot of time with a repeated mental stimulus, neural circuits that control that stimulation will strengthen at the cost of weakening other neural circuits. Basically, most of us are logging too much technology time, and we’re paying a price. We’re not engaging this powerful brain in activities like looking people in the eye, noticing nonverbal cues and emotional expressions, empathizing with other people. That’s a big concern in today’s technological world.

RH: So it’s not technology itself that’s the issue: it’s the fact that technology takes us away from so many other important social activities?

SMALL: Right. And there’s the very real issue of technology and addiction. Some people are addicted to video games or to shopping online or gambling online, and that can be destructive to their lives. Studies suggest it can worsen AD/HD, and it may even contribute to the development of autism spectrum disorders.

RH: When should therapists be concerned about a client’s relationship with technology?

SMALL: My alarm goes off if clients keep interrupting a therapy session because they’re answering texts or making calls or checking websites. Any time I see a patient with an inability to unplug for a while—someone who can’t have a conversation because he’s too busy messing with technology—I consider it an issue worth discussing.

RH: What impact might technology have on the future of therapy?

SMALL: Of course, many therapists already use technology in their practice. Video conferencing and the use of virtual-reality therapy for people with post-traumatic stress and phobias or obsessive-compulsive disorders are increasingly common. There are applications you can download to help with mood and anxiety disorders. Clients can even wear sensors that will alert their therapist when they’ve reached a certain threshold point of anxiety. I think we can take advantage of technology to enhance therapy and increase its effectiveness.

RH: So you’re optimistic about our future with technology?

SMALL: I have faith in humans, and I think we’re going to make the right decisions. We need to bear in mind that technology is neither all good nor all bad. The challenge is to integrate it into our lives, rather than let it become something that enslaves and controls us.

But with young kids, I do have a special caution. The parents of small children have a responsibility to make sure they don’t overuse it and that they spend plenty of time offline. For adults, same thing: don’t spend hours and hours just answering your email. As with so many other issues in life, it’s a question of balance and putting things in perspective.

Ryan Howes

Ryan Howes, Ph.D., ABPP is a Pasadena, California-based psychologist, musician, and author of the “Mental Health Journal for Men.” Learn more at ryanhowes.net.