Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

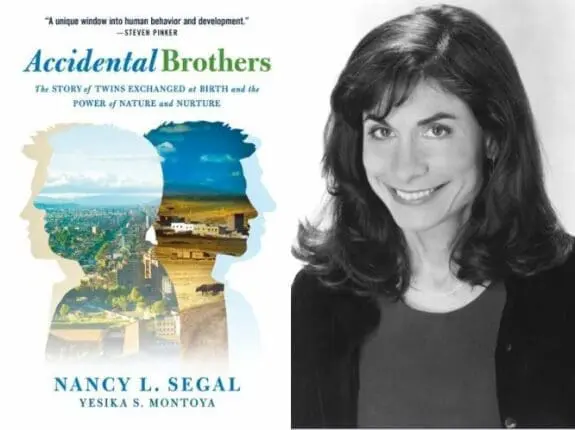

Accidental Brothers: The Story of Twins Exchanged at Birth and the Power of Nature and Nurture

By Nancy L. Segal and Yesika S. Montoya

St. Martin’s Press

318 pages

978-1250101907

Tales of babies accidentally switched at birth are the stuff of new parents’ nightmares, but such cases are rare, as are those of identical twins raised apart from one another. Rarest of all is the recently uncovered stranger-than-fiction, true-life story of two sets of identical twin babies who were accidentally switched at birth and then raised apart. The sets of twins were 25 years old by the time the facts came to light.

How they and their unexpectedly entangled families took in this life-upending news is the subject of Accidental Brothers: The Story of Twins Exchanged at Birth and the Power of Nature and Nurture by psychologist Nancy Segal, founder and director of the Twin Studies Center at California State University, and her coauthor, social worker Yesika Montoya. The book is valuable for the sensitivity of its clinical insights and its in-depth assessment of twin research studies. Chapter by chapter, the authors balance the gripping details of the narrative with an exploration of the dueling impacts of genetics and environment in shaping who we are. But more than a tale of nature vs. nurture, it’s a story about family bonds, regardless of biology, that are tested to their limits and that nonetheless manage to endure.

The saga began in a chaotic hospital ward in Bogotá, Columbia, in December 1988, when the identity tags of two baby boys were inadvertently swapped. It was this initial error that reconfigured the two sets of identical twins into two sets of unrelated baby boys and set in motion all that followed. Each of the accidentally switched babies required additional medical attention from the get-go, and neither mother had more than a brief glimpse of their babies before they were whisked away for further care. When the babies were subsequently “reunited” with their incorrect mothers, each pair still had one newborn twin who was more fragile than the other.

Since no one initially realized anything was amiss, each family accepted and raised each reconfigured pair lovingly as their own. Certainly, as the babies grew, each family noticed the complete lack of resemblance of one supposed twin to the other—or, for that matter, to any other biological relative. But the parents thought that if any mistake had been made, it was by the doctors who’d initially called the babies identical twins, rather than fraternal twins.

What the families didn’t yet know was that a variety of genetically inborn traits would express themselves similarly in both sets of mismatched twins. Most strikingly was the way each pair got along (or not) with each other. For example, for as long as they could remember, each set of “fraternal” twins had constantly squabbled with each other over similarly disparate qualities, such as their different ways of evaluating a situation (with one’s even-tempered optimism typically arguing against the other’s more laconic skepticism) and their dissimilar needs for socializing (with one enjoying and excelling at getting along with people and the other preferring privacy). And yet, despite these differences, when it came time to move away from home, each mismatched set insisted on sharing apartments together. They were loyal, trusting brothers who loved each other, after all.

In these and other ways, their inborn natures responded in sync, despite their different family environments. Studies of identical twins reared together and apart, the authors report, have shown that genetic factors influence an array of “political perspectives, social attitudes, divorce tendencies, financial decision-making and religious involvement, behaviors previously thought to reflect how our parents raised us.”

But experience also plays an important role. In this case, the stark socioeconomic contrasts between the families added another dimension to the consequences of the switch. Jorge and Carlos, his presumed biological brother, were raised in the working-class, urban bustle of Bogotá, where they completed high school and went to college. Jorge worked as a mechanical engineer, and Carlos pursued a career in accounting and finance.

By contrast, Wilber and William, his presumed biological brother, grew up on an isolated farm without electricity and running water in the tiny town of La Paz, about 150 miles north of Bogotá. The farm work was physically demanding, social and cultural activities were extremely limited, and educational opportunities were almost nonexistent beyond grade school. After serving in the army together, they moved to Bogotá, where they found work at a small butcher shop.

Until then, only jokingly would the relationship between one brother to another (or to the rest of their extended families) be questioned. But it was no joke when, 25 years into their lives and all now living in the same city, as if in a comedy of mistaken identities, Laura, a coworker of Jorge’s, stopped into the small butcher shop and became utterly confused when the young man helping her insisted that his name was William. It was this incident that led to the unraveling of the identities of the mismatched twins—and their first meet-up with one another.

Their first get-togethers proved promising and friendly, fueled by curiosity as well as a surprising comfort and affinity that seemed to spring up automatically between each set of genetic brothers. But the head-spinning revelations raised essential questions for all four “brothers” about the meaning of identity, selfhood, family. To which family did they truly belong? How would this new information reconfigure—or break apart—the longtime relational bonds and loyalties they’d grown up with? Could they successfully redefine, within their own minds and lives, the meaning of family ties beyond shared blood (or the assumption of it) alone?

Answers are important because, as the authors acknowledge, switched-at-birth revelations have in several instances, which they also recount in the book, severely traumatized and distanced family members from each other. Fortunately for all concerned, that didn’t happen to the Columbian families, and the authors take care to explore why and how they reached a different outcome.

No doubt, the apparently inborn sense of understanding and impulse toward conciliation that the genetic twins Jorge and William shared helped them. But equally important to the positive unfolding is the extraordinary empathy shared by all four brothers, likely a result of the closeness that the family of each set of mismatched twins had always emphasized. After all, as the authors note, Columbian culture encourages strong family bonds and connections, which spurred the brothers to orchestrate trips to meet one another’s relatives in Bogotá and then in La Paz. In time, both sets of brothers came to embrace both families as their own extended relations. Most striking was the four brothers’ willingness to persevere in order to preserve their existing and newfound relationships in the face of fears, reservations, challenges to personal narratives and identities, and nagging questions of “what if.” Through it all, they kept talking, kept getting together, and kept finding new ways to laugh together and discover new depths of understanding each other.

But to arrive at that point, each of the four young men struggled in his own way, some with more obvious anguish than others. On the surface, Jorge, who’d been raised in Bogotá with his biological family, focused on the bright side, emphasizing that each of them had gained a “real” twin without losing the brother they’d grown up with. But he was acutely aware of the torment experienced by his mismatched twin, Carlos—so much so that he had the image of Carlos’s face tattooed on his chest to reassure his nonbiological brother of his undying solidarity with him. Making it even more meaningful, he placed this tattoo next to another depicting their deceased mother, who’d reared them both and whose love they’d shared.

Carlos and William, the two brothers whose switched baby ID tags had led to the mismatch, had to grapple with the hardest challenge, a substantial subsequent switch in life opportunities. Carlos, who was born to a poor family whose isolated rural home lacked basic modern amenities, was instead raised in the city by a learning-oriented, working-class family who provided him with a good education. He was overwhelmed with guilt and shame for having “stolen” someone else’s life, and “wanted to hold his head and curse because this mirror image [William] reinforced what seemed so clear: that he belonged with another twin [Wilber] in another family,” the authors write. He felt somehow culpable for having “benefitted” from the switch, though he was in no way to blame.

William, curious-minded and school-loving, was deeply aware that the switch had cost him the hopes for an education and a career he’d always harbored but could never attain. So it was understandable that his initial resentment of Carlos took time to heal. At the same time, the authors note, William felt that the truth “answered many questions he’d had about why he always felt so different from those around him.” Significantly, the revelations didn’t affect the love he felt for his La Paz family. And with the assistance and support of his newfound biological family, he’s been able to continue his studies.

Wilber, like Jorge, grew up with his biological family. Perhaps the intertwined roles of genetics and environment can be seen in the fact that he—unlike his genetic twin, Carlos—has never been particularly interested in an education. The authors comment, “It is impossible to know whether Wilber would have been more interested in education if he had been the twin who grew up in Bogota—he has the same mathematical interests as his reared-apart twin but never had the chance to explore his abilities to the fullest. It is also impossible to know whether Carlos, like his real brother, would have written off education had he grown up in the country, but it is certainly likely.” In sum, the study of reared-apart twins may provide clues to the roles of nature and nurture in shaping who we are, but it still can’t provide definitive answers.

Accidental Brothers has its flaws. It can be repetitive, and keeping track of who’s related by genetics and who by chance can be confusing. What makes this book and its story exceptional is the clear-eyed honesty, sensitivity, and compassion with which each brother, and each member of both these accidentally intertwined families, came to understand, adapt to, and live with the seemingly surreal circumstances of their situation. How they did so speaks to the power of the families’ strengths and to their innate humanity, qualities that allowed them to share, as their chief priority, a passionate commitment to remain connected, regardless of the composition of their DNA.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.