Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

If you haven’t heard of Tricia Hersey’s Nap Ministry by now, you might be living under a rock—or maybe you’re fast asleep. If it’s the latter, chances are Hersey will forgive you. After all, spreading the gospel of rest as a regular, intentional, and radical act of love—for ourselves and others—is her cri de cœur. Whether it’s as an activist, poet, performance artist, or New York Times bestselling author, Hersey has spent her career championing the idea that rest is how we escape the injustices of modern-day grind culture.

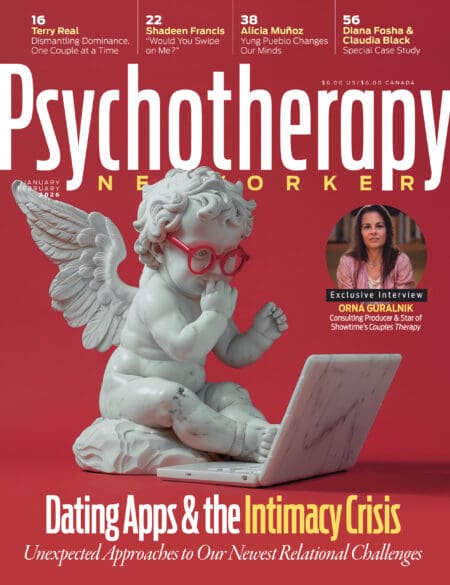

In 2016, Hersey founded The Nap Ministry, an organization that advocates slowing down, taking naps, and other feats of not-doing as racial and social justice initiatives. Within a year, Hersey—by now the self-proclaimed Nap Bishop—began leading Collective Napping Experiences in Atlanta and Chicago (where she’d taught poetry as a public-school teacher in the ‘90s). Her message spread like wildfire, as the burnt-out masses flocked to her collective napping experiences, immersive workshops, and performance art installations. Today, the Nap Ministry boasts over half a million followers on Instagram. Her work has been covered by The New York Times, Vogue, The Atlantic, Complex, and USA Today, among others. And her services have been sought out by Google, MIT, Brown University, and more recently, the Psychotherapy Networker Symposium.

Hersey’s 2022 book Rest is Resistance received critical acclaim—and notably, is dedicated to her father, Willie, a Black liberation theologian, church leader, and community activist who worked long, back-breaking hours as an employee for the Union Pacific Railroad. When he died in 2000 at the age of 55 following complications from a triple bypass heart surgery, Hersey knew that overwork had contributed to his early passing. She was likewise inspired by her grandmother, Ora, who made a deliberate practice of taking 30 minutes each day to shut her eyes and meditate on the couch—while a young Hersey tiptoed through the living room to avoid disturbing her.

Simply put, Hersey says, rest is our birthright. And in a society that equates success with labor and touts grind, grit, and hustle as virtues, it’s crucial that we remind ourselves of this right. Rest isn’t just another form of self-care, or simply a type of rebellion against grind culture, she contends: it’s an act of self-liberation from the lies and oppression of colonialism, capitalism, patriarchy, and other dehumanizing systemic forces that keep us on the metaphorical hamster wheel. “There is another way,” Hersey writes. “We can just be. We are beautiful. We are enough. We are escape artists. We will rest!”

On a recent afternoon, Hersey sat down with us to talk about her journey, the trap of grind culture, and how therapists can help promote radical rest in their own work.

Livia Kent: In your new book, We Will Rest, you write, “This is the story of a Black woman traumatized from capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy, so she decided to never be held hostage by the beast of grind culture.” How do those three things—capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy—translate to grind culture?

Tricia Hersey: The whole idea of capitalism—as a paradigm, a praxis, an economic system—was created from plantation chattel slavery, on the backs of indigenous and African people. Every time I name grind culture as a collaboration between white supremacy and capitalism, I’m always surprised that people don’t get it, because the blueprint that history has left us is clear.

Plantation labor was an experiment in the commodification of Black bodies. It laid the framework for the type of labor we see globally today: one that values profit over people. Capitalism and white supremacy are interlocked—the idea of labor as all-important combined with the idea of a body being a machine. That’s grind culture: a deeply violent collaboration between systems that don’t look at bodies as humans, and therefore don’t see us as full divine beings.

Given my training as a theologian, a womanist, and a human rights activist, I see all our different historical origin stories as interconnected and dependent on each other. So my message that rest is resistance is for everyone. Yes, this work comes out of a Black liberation lens, but Black liberation is a balm for the entire globe, for humanity. We’re so brainwashed by individualism that we tend to miss this interconnectedness. I’m hoping people tap into the fact that grind culture strips everyone of humanity, dignity, and divinity.

Rest is a divine right of every human being who’s breathing. I believe resting allows us to tap into the deep dream space that opens us to imagining the world we want to see, one that centers justice, equality, love, and healing. To do this, we need everyone rested and connected—and not burnt out and traumatized by systems that dehumanize us.

LK: A large part of your book illuminates the need to tap into trickster energy as a way to escape grind culture. Tell me a bit about that kind of energy.

Hersey: Most cultures have a trickster in their mythologies. There’s Br’er Rabbit from the African American oral tradition and Anansi the spider from African folklore. A trickster is someone who’s peeped a scam and uses their intellect to move against it. A trickster is a shapeshifter.

As a Black woman—who comes from a legacy of poverty, who’s a descendant of enslaved people, who was the first person in her family to graduate college and worked seven days a week and still had negative $25 in her bank account—I’m like the ultimate trickster. I decided to just say no.

When I was working three jobs to pay my bills, I felt something wasn’t right about the pace of life I was living, but I kept doing it because that’s what the culture called for: exhaustion and burnout. But then I listened to the secret knowledge of my body, and I started to rest. When I took naps, I tapped even deeper into the intellect of my own body, into the dream space that was available to me and the information provided there by my ancestors. I just said, Hmm, I’m going to experiment. I’m going to peep the scam and see how I can gain some reparations and re-imagine my body. The way I did that was to slow down.

LK: In addition to exposing the realities of grind culture, your work serves to unbrainwash people around the mainstream concept of wellness. What’s your take on wellness buzzwords like self-care?

Hersey: I believe being born is a miracle and everything else that’s put on us—capitalism, patriarchy, the healthcare system, the prison system, the food system, all of those toxic things that make it so hard for us to thrive in this culture—has been dreamt up in someone’s mind.

So when I think about going past the concept of mainstream wellness, I think of returning back to our natural state, doing the repair work that brings us back to who we really are as humans. All my work is simply an attempt to get us back to being more human. Indigenous people understand the idea that we’re not born just to do labor. We’re born to enjoy life and explore and be in community with each other.

I never mention self-care in my work. I talk about community care, the care of souls. To me, wellness is not something outside yourself: it’s not something to gain or buy. It’s what we already have—and the process of coming back to it is a meticulous unraveling that involves the practice of loving ourselves and others.

LK: There seems to be a growing movement in the mental health field to go back to its roots in family therapy and systems thinking, which is a more community-based way of looking at mental health than the one-on-one, individual model of healing.

Hersey: I think that collective energy is what we need. We can’t heal alone. That’s why I’ve dropped the word self-care. We’ve had enough of the self. It’s been co-opted by the wellness industry, by capitalism. It’s an ancient thing to be in deep community, to understand what the care of a community looks like, feels like. I hope my work helps people get curious about that, at least enough to be like, Hmm, interesting. Let me sit with that for a while.

Sometimes that invitation doesn’t feel like enough for people; they’ve been socialized to expect a ready-made solution, a 10-point plan with an exact outcome for what to do instead of “self-care.” But that’s not how life works. Life is not some laboratory of exact, predictable processes; it’s a playground. I just want people to start being more curious. That’s all this work is for me. I’m just a curious, exhausted Black woman being like, Hmm, let’s see. If I just lay down, what would that look like?

LK: Another buzzword you challenge is burnout. You call it “a scam, a language created by agents of grind culture, guided by corporations tricking you into believing it’s a normal and regular part of any working person’s career.” You write, “There is no ‘burnout.’ There is worker exploitation, abuse from capitalism, and trauma stored in our bodies from a lifetime of overworking.” How does this not sink you into a pit of hopelessness, especially in this political climate?

Hersey: As my grandmother would say, “This joy that I have, the world didn’t give it to me, and the world can’t take it away.” To me, that means we can’t fall victim to the dips and valleys a toxic, violent culture throws at us every four years. We’d be spinning ourselves dizzy if we always reacted in a way that took us off the path of who we are. Instead, this is a time for us to really tap into the miracle and the power of our bodies.

Patriarchy, ableism—all the systems that have taught us our bodies are nothing except a problem to be fixed, that have taught us to hate ourselves and the power we have—only mean that we have to come back to our bodies as brilliant, amazing sites of deep liberation. That’s the true work: to be rooted in the possibility of the power I have as a human and the power we have as a community.

Personally, I hold this annoying, relentless hope that the world can be better. That’s just how I feel. It’s what keeps me grounded in community. I think about my ancestors, who I wrote about in my first book. They were enslaved on plantations, told that they weren’t even human beings, and they were still like, Okay, but I’m going to go over here and build a whole other community outside the plantation. I’m going to make blues music. I’m going to dance. I’m going to have babies. I’m going to cook. I’m going to create in community and tap into what I know to be true.

I want people to tap into that kind of trickster energy. I think that that’s what’s going to save us. Community care is going to save us. Slowing down is going to save us.

LK: Boundaries is another word that comes up a lot in the therapy space. These days, more and more people want to have hard, firm boundaries: at work, with family members, with partners and friends. But in your book, you say that boundaries should feel like fresh clay. I love that.

Hersey: Boundaries should be flexible. What happened yesterday may not be how I’m feeling today. What my body needs at two o’clock might be different at 11 o’clock. But too often, we move at such a fast pace that we can’t even stop long enough to feel that difference. Resting provides a moment for us to tap into what’s truly going on in the present. It removes the veil from our eyes and gives us an opportunity to tap into what we already know.

The systems have done a great job of making us loathe ourselves to the point we think we have to buy things and get outside of ourselves to feel whole. Resting, just pushing back a little, is a deep and meticulous act of love toward ourselves, our communities, each other, and the collective. All I want to do is be on books for having raised my hand and said, “No, you can’t have me. I know you’re lying. I know I’m enough. I know I’m love. I know I’m beautiful and special simply because I’ve been born.”

LK: I wonder if you think of therapy as a space to slow down. In your view, are enough therapists facilitating the kind of work you’re talking about?

Hersey: I love that so many people come to The Nap Ministry because they hear about it from their therapist. It shows just how often mental health professionals are hearing about people’s exhausted state and are able to say, Oh my goodness, you need to rest. In this sense, my work seems to serve as a flotation device, something to hold as people try to slow down and heal from all the expectations the systems have placed on them.

LK: You mention that in the silence of rest, guilt and shame will inevitably come up. And you tell people to rest through the guilt and shame, too. When I read that, I just wanted to lay down and cry. I’m not sure why, but that was my reaction.

Hersey: Because resting through that is labor, and you’re already exhausted. But those difficult feelings are beautiful information. When we feel those things, we can say, Oh, I never knew that I’d been brainwashed and socialized to the point where I don’t even think that I’m deserving of rest. The systems at play are very violent. We have to grieve that, and go back to gathering information, being a trickster, being open, tapping in, closing our eyes and seeing what else is available to us in the dream space.

LK: When I hear that, I think of another motif in your book: improv. Improv is about finding alternatives, right?

Hersey: Yeah, improv shows you that there’s always another way. There’s always another way. I learned that from my grandmother. That’s the ongoing groundedness of hope. And I think it’s okay not to know what that other way is all the time. I love the mystery of not having things wrapped up in a bow.

LK: You give people an invitation, a doorway, not an answer.

Hersey: I call my book a portal. I call it a daydreaming tool. I want people to pick the book up, feel the paper, the weight of it, all the art, the space in it, the incomplete steps in it; I want them to feel the experience of turning each page and starting to slow down.

That’s part of why I didn’t want a table of contents, so readers can get a bit lost and discover something new as they search around.

LK: Beyond your books, your work is also about creating collective rest experiences, physical spaces for people to rest and daydream. What does that look like?

Hersey: It started with me and some yoga mats and pillows and blankets and lavender oil, and just going out to communities and inviting people to experience what it feels like to rest in community. I’d also hold space for them to discuss the experience afterward.

This is deep liberation work. It’s not wellness work; it’s justice work. Now, people all over the world are expanding on that idea. They’re hosting rest events without charging people, integrating sleeping and collective resting and daydreaming and slowing down into their daily lives. People always ask things like, Are you going to start training programs? Can I get certified as a nap minister? That’s the white supremacy culture coming in, needing to colonize everything and make a profit. I’m like, You’re already certified because you’re alive. You just need to be what you already are: a divine human. That’s what the work is about.

Photo credit Charlie Watts

Tricia Hersey

Tricia Hersey, BA, MDiv, has over 20 years of experience as a multidisciplinary artist, writer, theologian and community organizer, and is the visionary founder of The Nap Ministry. Her work is seeded within the soils of Black radical thought, somatics, Afrofuturism, womanism, and liberation theology. She’s the author of the New York Times bestselling book Rest is Resistance: A Manifesto, The Nap Ministry’s Rest Deck: 50 Practices to Resist Grind Culture, and We Will Rest! The Art of Escape. Contact: thenapministry.com.

Livia Kent

Livia Kent, MFA, is the editor in chief of Psychotherapy Networker. She worked for 10 years with Rich Simon as managing editor of Psychotherapy Networker, and has collaborated with some of the most influential names in the mental health field on stories that have become widely read articles and bestselling books. She taught writing at American University as well as for various programs around the country. As a bibliotherapist, she’s facilitated therapy groups in Washington, DC-area schools and in the DC prison system. In 2020, she was named one of Folio Magazine’s Top Women in Media “Change-Makers.” She’s the recipient of Roux Magazine‘s Editor’s Choice Award, The Ledge Magazine‘s National Fiction Award, and American University’s Myra Sklarew Award for Original Novel.