Children at any age can be difficult to parent and nurture for many reasons, especially when trauma has shaped their early life experiences. When difficulties arise between parent and child, most therapists naturally focus treatment on the child. But the parent–child bond is a two-way street, and parents come with their own history, which can impede an already challenging child’s ability to attach. Additionally, feelings of connectedness and safety are usually relayed in nonverbal ways that therapists too often ignore: through small moments of eye contact, touch, rhythmic gestures, warm smiles, and ultimately the sharing of joy and delight. But how do you go beyond words to cultivate a deeper sense of attachment in therapy? How do you help a child and parent who are both contributing to the disconnection in their relationship? One such mother–daughter case challenged me recently to take a closer look at this two-way street.

Elaine, a single mother living in the Midwest, had adopted Natasha at age nine from a Russian orphanage. Adoption records indicate that Natasha had been found alone in a dirty apartment without food or heat several times before she’d been sent to live at an aunt’s home at age five. Three years later, she’d been removed again because of neglect and sent to an orphanage, where she’d lived until the time of her adoption. During her first year with Elaine in America, Natasha recounted stories about scary men coming in and out of her parents’ apartment and the police arriving many times to break up arguments. But by the second year, she was no longer speaking about her life in Russia.

When I first met with Elaine, she described 13-year-old Natasha’s behavior as a combination of icy disengagement and fiery rage. Her default mode of disengagement seemed almost robotic: she often retreated to her room and answered even the most benign questions in apathetic grunts. One time, when Elaine tried to raise Natasha’s pant leg to check out what seemed like a nasty bruise from being kicked on the soccer field, Natasha pulled her leg away and spat with disgust, “Ew, you’re gross!”

This constant rejection of Elaine was coupled with fits of rage that would erupt without warning about seemingly trivial things. For example, after Elaine said no to buying Natasha an expensive jacket online she didn’t need, an enraged Natasha started crying and shrieking, “You don’t love me! You just adopted me so you could be mean to me!” She flung papers off the desk and threatened to throw a paperweight at her mother’s head. Usually, scenes like this would end with Natasha running to her room and slamming the door so hard it’d shake the rest of the house. If Elaine tried to knock gently and enter, Natasha would snarl, “Get out of here! I hate you!”

Elaine was living in a state of constant stress, amplified by a growing dread of interacting with Natasha, given her avoidant style and hair-trigger temper. Weeping openly, she told me she was deeply ashamed of the way she felt and how she was failing to connect with her own daughter.

“Natasha had a very difficult time in her early years, and it sounds like she built up some pretty tough defenses. You’re doing the best you can,” I assured Elaine. “Life with any girl her age can be difficult, but I think we can find ways to make sure you can build up a foundation of trust and support. Soon enough, you’ll even be able to enjoy spending time together.”

Although her tears continued to flow, they now seemed to express her relief. “So there’s hope,” she said, almost to herself, as she reached for a tissue.

Surprise Paper Punch

When Natasha first walked into my office with her mother, she struck me as a sad baby stuck inside a teenager’s body. She avoided looking at me, and pretended not to hear my questions or know the answers, even when I asked something simple like, “What’s one of your favorite foods?”

“Huh?” she responded with a blank look as she played with the tassels on her boots.

Her mom sighed with exasperation and elbowed her, saying, “Come on. It’s empanadas!” Natasha returned an empty stare, which made Elaine look at me and roll her eyes.

As with most traumatized children I work with, I knew my first task was to transmit to Natasha that she was safe—at least safe enough to peek out from her protective shell and see if there could be something worth taking the risk of letting her guard down for. Clearly, talking and asking questions wouldn’t get us far, nor would initiating any activities that asked for her overt cooperation. But in these situations, I can often find ways to help parents and children connect through attachment-based games that involve elements of silliness, movement, and surprise.

So when Natasha came into the next session looking at the ground and picking the polish from her nails, I surprised her by asking, “Do you have strong arm muscles?” I turned to Elaine and asked, “Is it ok if I check how strong your daughter is?”

“Sure,” Elaine said.

Puzzled, Natasha immediately looked at her mom and then at me. She seemed genuinely curious, so I said, “Okay, Natasha, I’m going to have you punch a hole in my newspaper with your strong muscles. Are you right or left handed?” She lifted up her left hand. “Wow! You’re left handed? I’m a lefty in sports!”

Next, I asked her to make a fist with her left hand, and when she held up it up, I cupped it with both my hands, looked her squarely in the eyes, and said with a resonant voice, “Oooooh, that’s a good fist.” I then reached for a big sheet of newspaper and spread it open in front of me. “Now, with this fist, I want you to punch a hole right here in the center of my newspaper when I say ‘One, two, three, punch.” I pointed right to the center. “I have my arms extended way out, so you don’t have to worry about hurting me when you punch the paper,” I added.

Natasha nodded cooperatively as she readied herself to respond to the signal. “One, two, three, punch!” I said with vigor. Natasha threw a precise, purposeful fist through the paper, and I simultaneously pulled at each side. The newspaper tore in half cleanly and with a resounding POP! Natasha looked stunned and impressed.

“Wow!” I yelped, mirroring her reaction. Natasha glanced sideways toward her mom, giggling at what she’d done as Elaine beamed with pride. Surprisingly, Natasha leaned toward her mom’s arm for a moment. She then sat erect again, and we repeated the process a few more times. Each time we set up the game, I looked at Natasha with excitement, my eyes signaling something good is about to happen, which she reflected back to me. And when she punched and I ripped the paper in concert, Natasha repeatedly looked at her mom and giggled like a baby. Elaine too opened her eyes wide and gave out an admiring “Wow!”

Natasha’s laugh was genuine and I could tell that Elaine was both pleased and surprised to hear her daughter’s laughter. “I love to hear you laugh. That’s the best sound in the world!” she said at one point. For the next few sessions, we continued these types of playful games filled with laughter and surprise that got around Natasha’s defenses. Session by session, she became softer and more present. When I’d ask her about school, soccer, friends, even some of the things that made her so angry at home with her mother, I noticed her responding not only to me in this way, but also to Elaine. I was hopeful that these small moments of connection and shared laughter would provide the basis for real therapeutic progress.

Real-Life Slippery Slip

When Elaine came in for an individual session, however, I was surprised to hear her say that she couldn’t see any changes in her daughter outside the therapy room. She told me she still experienced dread when approaching Natasha and felt ineffectual and unable to connect at home.

When I described my experience of Natasha opening up to her in our sessions, Elaine said she thought Natasha might just be “faking it.” I was shocked to hear her say that in such a matter of fact way, so devoid of hope. I realized I’d have to do some deeper work with Elaine to understand the meaning she ascribed to her daughter’s behaviors and explore her how her own attachment history might be contributing to their challenges.

To start, I cued up a videoed segment of our last session with Natasha, where a particularly moving interaction had occurred between them. The game, called slippery slip, involved Natasha and Elaine sitting crossed-legged and facing each other on the floor. Using lotion to make her hands slippery, Elaine held hands with Natasha and leaned back while trying to maintain her grip on her hands. Naturally, there was a gradual slipping away, which ended with a dramatic falling backward, followed by a springing back up.

In the clip, Elaine was holding Natasha’s hands, and both were poised in identical postures, eyes wide open, in anticipation. As Elaine began to say dramatically, “Oh no, I’m slipping awaaayyyyy” Natasha let out a rolling giggle until they both exploded in laughter as they let go. Elaine leaned all the way back to the floor and rested there for a moment. Natasha had also leaned back, but then immediately sprang back up, ready for more. She’d been locked in on her mother’s gaze, and when it was momentarily lost, she yearned to get it back. Natasha extended her arms out fully, and like a baby, clapped them together three times and squealed, “Come on, Mom!”

The first time Elaine watched this clip, she seemed mesmerized but also a bit in disbelief. “What do you see, Elaine?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” she said with a searching expression on her face. I played it for her again, and this time Elaine observed, “It looks like she’s really having fun with me.”

I looked at Elaine. “Yes, she really enjoys playing with you. Did you see her reach her arms out to you? How do you feel when you see that?” I asked.

“I want to believe that she needs me, but part of me still thinks she’s faking,” she answered.

Then a look of sadness swept across her face. “Elaine, I’m wondering: did you ever get to feel this way when you were a child—that your mom or your dad or someone really felt true delight in being with you?” I asked. “Like someone sought you out just because they felt pleasure in your company?”

“I don’t know,” she responded.

I probed further. “For example, can you think of a time when your parents cuddled with you, or held you in a way that made you feel special?”

Elaine paused. “I can’t remember that kind of moment. My parents were really busy, and there were a lot of us kids. They weren’t really the affectionate types. But I remember when I got my first cat,” she recalled. “I was 24 and had rented my first apartment. I got this idea that I was going to adopt a stray, so I picked out a fluffy, gray fellow from the shelter. When I brought him home, I sat on the couch and watched him explore the place. I was so struck by how bold he was to go nosing around every corner. And then he hopped up on the couch next to me and started rubbing his back and tail against my leg, like he was wanting me to pet him. And I thought to myself, What did I do to deserve this cat’s affection?”

Elaine seemed to be experiencing a deep sorrow as she relayed this anecdote. So we spent the next few sessions exploring this feeling of not being truly worthy of love, and how it now intersects with the challenge of raising a child who’s often distant and sometimes frightening. At one point, remembering how she’d had to stay home from school a lot as a child because of respiratory problems, she recounted that although she was physically taken care of and had plenty of medicine and juice by her bed, she’d often wait desperately for the hours to pass until her mother or father would come home. When they did come home but didn’t go straight to check on her, she’d feel so hurt that when they finally did go up to her room, she’d act as if she didn’t need them.

It began to dawn on Elaine that beyond the security of a stable home and a good school, the need she wanted to fulfill for Natasha was one of feeling really special and connected, as she’d wished for herself as a child. While this new feeling of longing to mother Natasha stirred inside her, she felt increasing worry that she wouldn’t be able to rise to this level of connection. At that point, I replayed the video segment of the slippery slip game, where she and Natasha had been giggling and moving in sync with each other.

“I understand why you’re worried about connecting with Natasha,” I told her. “You didn’t get this when you were a child, so you don’t know what it’s like to give it. Plus, part of Natasha doesn’t want a mom—and she lets you know that, loud and clear. But I also think Natasha recognizes the mom part of you. She sees you gazing into her eyes. She sees you delighting in her laughter as you pop back up in the game and say, ‘Here I am!’ And her eyes are saying back, ‘I want you, Mommy!’ You know how I know? I can see it in her eyes, how she looks into your gaze in anticipation, how she synchronizes to your movement, how her giggle crescendos with your ‘oooh nooo.’ She’s communicating to you with her body, and those signals can’t be faked.”

Although Elaine had watched this clip several times in the past, it was as if she was now seeing its emotional undercurrent for the first time and accepting the possibility that she could actually earn her daughter’s affection.

A Nightmare No More

Natasha and Elaine soon began to pick up positive cues from each other in their day-to-day interactions, cues that had previously gone unrecognized. In subsequent sessions, Elaine reported that Natasha had begun seeking her out in ways that were small but immensely heartening. One day, for example, Natasha had emerged from her room and nonchalantly asked Elaine if she’d make her some ramen noodles. Elaine was more than happy to oblige, but asked in amusement, “How come you’re not making them yourself?” to which Natasha responded with a smile, “They taste better when you make them.”

Elaine’s confidence as a mother began to blossom the more she felt that Natasha trusted her and wanted to be with her. And in therapy, Elaine continued to learn to be present and supportive in ways that were more palatable to her daughter. In one particularly difficult session, we were exploring a nightmare that Natasha had had the night before. In it, Elaine had died in a car crash, and Natasha had to move to a stranger’s home in California. Barely managing a weak whisper as she described it, Natasha asked her mom to recount the dream.

Elaine used a tender voice to describe not only the dream as Natasha had relayed it in the middle of the night, but how she’d found her looking panicked and grief-stricken. She said it must have been frightening for Natasha to have woken up from a nightmare like that.

“It happens a lot,” Natasha mumbled.

“I know,” Elaine said. “I hear you at night when you call out in your sleep. I always want to go in and comfort you and let you know that I’m here for you.”

“You’re doing that now, Elaine,” I noted.

Natasha laid her head on a pillow, leaning in her mom’s direction. Elaine put her hand on Natasha’s thick hair and tenderly began to stroke her head. The three of us sat in silence for several minutes. Natasha’s breathing became deeper and more rhythmic. Looking at Elaine, I saw the warmth of a mother with a steadfast dedication to comforting her child.

Soon after, Elaine told me about an episode at home where Natasha had gotten extremely angry about something and had run to her room crying. Previously, Elaine would’ve felt helpless to approach her daughter, but this time, she went to Natasha’s door with a sense of confidence and gently knocked. When Natasha didn’t respond, Elaine cracked the door and peeked in. To her amazement, Natasha didn’t scream at her to leave her alone, so she went over and sat beside Natasha on the floor. Eventually, she put her hand on Natasha’s back, and the two of them stayed there until Natasha sighed and asked for a glass of milk. As she walked to the kitchen to get Natasha the drink, Elaine described feeling a sense of euphoria. She reflected on it by saying, “I finally felt I knew what to do to make my daughter feel better.”

In this incident, Natasha and her mother had momentarily slipped away from each other, falling backward, and both had been able to spring back up and reconnect, just like in the attachment-based game we’d played early on. Those brief moments of playfulness at the start of our journey had laid the foundation for their new level of connection. Now, with Natasha able to go to her mother not just for comfort but for joy, they were ready for the next slippery slip, and the one after that.

As treatment continued, Natasha increasingly learned to rely on her mother for her basic needs. For example, when Natasha revealed she couldn’t sleep with the windows open in the summer because she was scared someone would kidnap her, Elaine immediately reassured her that they’d lock the windows and use the air conditioning to make sure she’d feel safe. Comforted by that response, Natasha asked her mom if she could sleep with her in her bed. Elaine felt a new confidence in her immediate response: yes. She reported that Natasha seemed much calmer and more cheerful after that, and had returned to sleeping in her own bed after a few days.

With their deeper grounding in security and trust, it became increasingly clear to me that Elaine and Natasha could handle the next step of their journey more on their own. I suggested we shift our weekly sessions to monthly check-ins. They looked at each other, and Elaine responded, “This is our special time to just be together and have fun, but I guess we have more of that at home now.” Without breaking eye contact with her mom, Natasha nodded in agreement.

Case Commentary

By Scott Sells

Dafna Lender describes a case in which she creatively engages a single mother, Elaine, and adopted 13-year-old daughter, Natasha, in family trauma treatment, nicely illustrating the use of joining, enactment, reframing, and strategic directives along the way. She immediately decodes the key theme driving Natasha’s symptoms of disengagement alternating with fiery rage, and early on discovers that Elaine doesn’t have the skills to emotionally attach to and nurture Natasha. But Lender never gives up on the mom or daughter.

Recognizing that asking straightforward questions or overtly requesting participation from Natasha leads nowhere, she uses attachment-based games as a catalyst to bring about small moments of connection between mother and daughter. In one instance, she asks Natasha to show her strength by punching through a newspaper, increasing the energy and engagement level in the session. In another, she skillfully uses a game called slippery slip to foster a new interactional pattern or feedback loop of playfulness and fun. Lender then introduced this new feeling between mom and daughter to other areas in their relationship, until nurturance became a new normal. This is a brilliant example of how a strategic directive or technique can bring about new and healthy patterns of interaction between family members and heal trauma symptoms.

The defining moment in treatment comes when Lender is able to link the mother’s own experiences as a child to her present-day difficulties with her daughter, exploring how Elaine never felt that her parents genuinely enjoyed being with her and how that informs her struggles to simply be with Natasha. Once this connection is made, Lender is able to experientially develop that theme and gradually build the mother’s confidence as a parent.

I’m only concerned about two issues. First, with clients like these, it’s important to normalize and educate the family that if signs of relapse do happen (a return to aggression or a feeling of detachment, for instance) one or two tune-up sessions might be necessary to get things back on track. Second, what about Elaine’s extended family? Why were they not mentioned or directly involved in sessions, even via phone if travel was an issue?

I nonetheless applaud the way this case was handled, as too often trauma-informed treatment focuses exclusively on the child without active parental or caregiver involvement. Lender’s work presents a clear illustration of why a family systems lens is so invaluable and why a child’s trauma is so often interconnected to a parent’s own early life experience.

Scott Sells, PhD, is the CEO and founder of Parenting with Love and Limits. He’s the author of Treating the Tough Adolescent and Parenting Your Out-of-Control Teenager, and coauthor of Treating the Traumatized Child: A Step-by-Step Family System Approach.

Want to earn CE hours for reading this? Take the Networker CE Quiz.

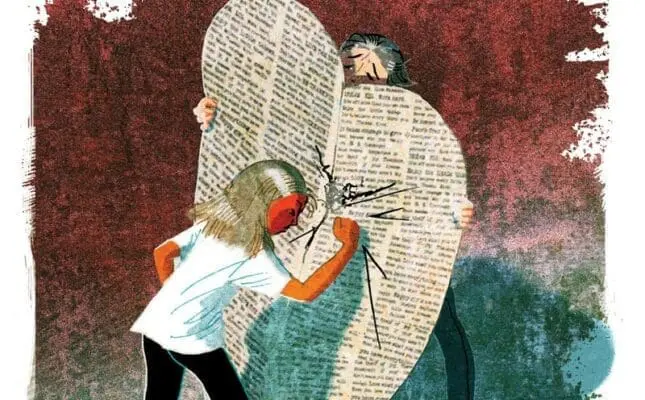

ILLUSTRATION BY SALLY WERN COMPORT

Dafna Lender

Dafna Lender, LCSW, is an international trainer, supervisor, and consultant in both Theraplay and Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy (DDP) who teaches and supervises clinicians in 15 countries in English, Hebrew and French. Her expertise is drawn from 25 years of working with families in at-risk after-school programs, therapeutic foster care, in-home crisis stabilization, and residential care and private practice settings. She’s also the co-author of Theraplay: The Practitioner’s Guide. Visit www.dafnalender.com.