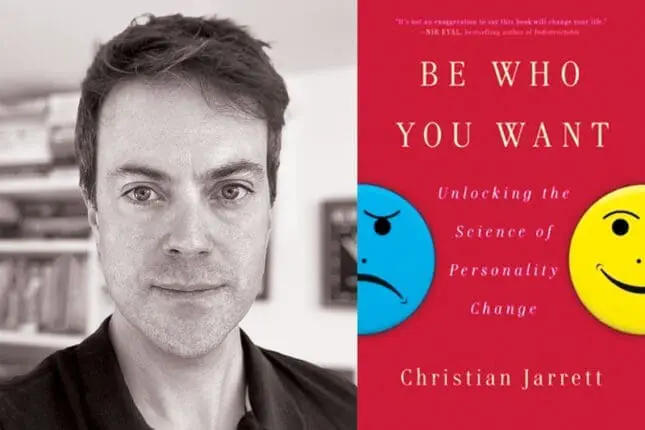

Be Who You Want: Unlocking the Science of Personality Change

by Christian Jarrett

Simon & Schuster. 304 pages

978-1-501-17469-8

I began reading cognitive neuroscientist Christian Jarrett’s engaging and instructive new book, Be Who You Want: Unlocking the Science of Personality Change, just as the country was emerging from the pandemic-imposed cocoon that had kept most of us isolated indoors for more than a year. It seemed particularly timely because, as I began dipping back into socializing in person, I noticed not just how much the year of living remotely had affected my friends’ moods, but in some cases how it had brought out unfamiliar aspects of their personalities, especially increased anxiety and depression.

At the same time, I was struck by how other friends had become more empathetic, more caring. Even amid so much illness and loss and worry, they’d managed to develop or discover new strengths and strategies within to help themselves and those around them.

According to Jarrett, in all these instances, different aspects of our personality had been challenged, disrupted, and changed, just as our lives had been. Such shifts might not have been expected, but they were normal—and with psychotherapeutic tools and support, the positive changes could be strengthened and the not-so-welcome ones could be made, well, more welcoming.

Jarrett begins by defining personality as “a relatively stable inclination to act, think, and relate to others in a characteristic way,” including our motivations, thought patterns, moods, temperament, and how much we do (or don’t) like to socialize or remain private. Various traits and attributes—the major ones are extroversion, neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeability, and openness—further contribute to the mix. Combined, he writes, they add up to “the kind of person you are.”

But that doesn’t mean that those elements are completely fixed. Our environment, life experiences, and desire to change play a part. Better understanding the ways in which the push-pull between those aspects plays out, he contends, can help us polish our rougher edges and sometimes even help instigate deeper changes.

In other words, adaptation is key. Still, genetics does contribute to our personality mix—just not nearly as much as psychologists (including such renowned figures as William James) once believed. “Between 30 and 50 percent of the variation in personality between people stems from the genes they inherited from their parents and the rest to differences in their experiences,” Jarrett writes.

That directly relates to the findings of a 2018 study of approximately 2,000 participants that measured the strength of five core personality traits—conscientiousness, agreeableness, openness to experiences, extraversion, and emotional stability—when the participants were 16, and then 50 years later, at the age of 66. The results showed stability; those who were more conscientious than their age cohort at 16, for instance, tended to remain so at 66. But there was also change: most people had grown more conscientious, agreeable, and emotionally stable over time, while others had changed in maladaptive or harmful ways. Overall, 98 percent of the participants showed significant change in one trait and almost 60 percent showed change in four traits.

Given the plasticity of personality over the course of a lifetime, the issue is therefore less about nature versus nurture than it is about how we can most successfully harness our temperaments to adapt to and cope with life at each of its stages and make our way through particular challenges. “Your genetic disposition makes it more likely that you might settle on some strategies more than others, but it doesn’t confine you to one approach to life and relationships and you are not stuck with your current way of being,” he writes.

That’s why, he suggests, it’s best to think about the character traits that come most naturally to us as default factory settings, which can change over time—and sometimes must be tweaked if we wish to thrive most fully. And with the pandemic having upended so many aspects of life, some fine-tuning may be more in order now than ever.

This is where psychotherapy comes in. Researchers are now starting to consider therapy itself a form of personality change, Jarrett writes. He cites a 2017 article by University of Illinois psychologist Brent Roberts, which reviewed 207 articles published between 1959 and 2013 that measured the before and after therapy results of 20,000 patients. Roberts found that “just a few weeks of therapy tended to lead to significant and long-lasting changes in patients’ personalities, especially reduced neuroticism but also increased extraversion,” Jarrett writes. Cognitive behavioral therapy, which focuses on ameliorating the anxieties and changing negative habits of thought about how we relate to others, is particularly successful, Jarrett notes, for treating the downward spiral of isolation, self-doubt, and angst wrought by depression and the devastatingly dark personality changes it can bring.

Chapter by chapter, Jarrett guides readers through the process of change, starting with an overview of major personality traits, a discussion of each one’s pluses and minuses, and a Q & A to help readers identify which traits they do and don’t favor. From there, he progresses to observations on the impact of a variety of the ups and downs life brings, both more common (having to do with growing up, marriage, kids, job loss, grief) and less so (brain injury, dementia, serious illness).

Throughout, Jarrett places the possibility, and the motivation, for change within the context of the way our lives unfold, influencing and shaping the course of our experiences and relationships, for good and bad. For him, personality is and must be plastic, helping us accommodate to hurdles and disappointments, small and large. But he also tackles the more difficult subject of how addicts and prisoners have managed to reinvent their lives. In these instances, he has found, finding a new purpose (volunteering to help newly released prisoners or people with mental illness, for example) or working toward a personal goal (such as an educational degree) have been particularly effective in both motivating and maintaining change.

Psychotherapists may find some of Jarrett’s ideas and strategies familiar, but the accessibility of his presentation style will provide clients with a deeper understanding of how change occurs and might well help persuade those wary of therapy of its efficacy. Each chapter contains a variety of self-help tests and tips. Perhaps most useful are the lists of “Five Actionable Steps to Change Your Personality” included in each chapter: one step for each of the five major personality traits of neuroticism, extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeability and openness.

The potpourri of activities, exercises, books, apps, suggestions for setting and keeping track of goals, you name it, amount to a pep talk to propel you toward change. Even if some of these are a bit familiar—for instance, I regularly use self-talk tropes, based on cognitive behavioral therapy, to remind the introverted side of me not to be afraid to speak up or speak out—I was happy to be reminded of how effective the techniques are.

Most of all, in portraying the science of personality change, Jarrett provides a prescription for resilience, a pathway we can all follow as we find our way back to in-person, post-pandemic life.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.