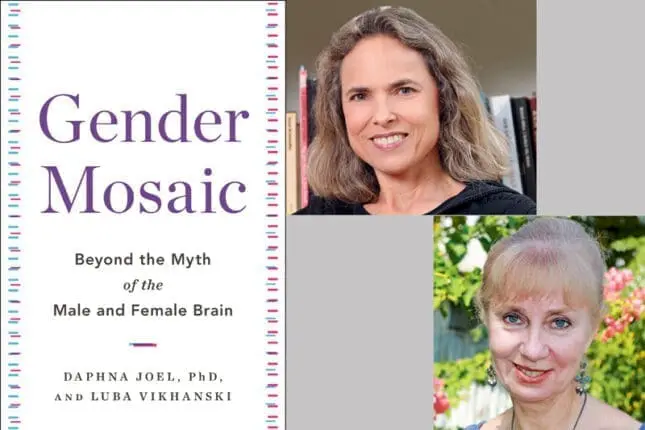

Gender Mosaic: Beyond the Myth of the Male and Female Brain

by Daphna Joel and Luba Vikhanski

Little Brown Spark

216 pages

Cultural stereotypes can have long lives. Many of us might have hoped, for instance, that the misnomer that male and female brains come preprogrammed with gender-defined intellectual aptitudes, personality characteristics, and interests would’ve long since disappeared by now.

But as recently as 2017, Google engineer James Damore brought back the canard in full force. He wrote a memo that soon went viral, citing inherent biological differences as the reason that women weren’t suited for science and tech jobs. Inborn sexual difference, rather than sexual discrimination, he asserted, was the actual reason for the presence of so few female software engineers in Silicon Valley. His comments echoed the 2005 utterances of Lawrence Summers, then president of Harvard University, who attributed the dearth of women in top science positions to what he called “issues of intrinsic aptitude.” In both cases, biased stereotypes about the relative inferiority of women’s brains were being casually spouted as fact.

But what are the facts? Enter Gender Mosaic: Beyond the Myth of the Male and Female Brain, in which neuroscientist Daphna Joel and coauthor Luba Vikhanski present a rich body of scientific research to disprove and debunk, once and for all, the presumption of the supposedly inferior female brain. In bringing rigorous research—as opposed to mere assumptions—to the subject, the authors show that science can be an essential tool for combatting bias and even self-doubts resulting from deeply internalized cultural and social stereotypes about who and what we “should” be.

The authors further caution that the misnomer of a male–female brain divide has widespread implications that reinforce our societal tendency toward gender-binary thinking, which separates humans into only male and female, without taking into account the broad diversity of gender expression that exists. Indeed, Joel’s research has found that even cisgender individuals “are far less binary in their gender identities than might be expected.”

In one study, she asked 2,155 cisgender people to rate, on a scale of four (0 for never, 4 for always), how often they thought of themselves as a man or as a woman. The results were at once predictable—with most men reporting thinking of themselves as male, and most women thinking of themselves as female—and surprising, in that 35 percent of the respondents said they viewed themselves as both a man and a woman. Joel subsequently followed up with a larger, international study of 4,759 cisgender men and women about their gender identity. The results were similar, she reports, this time with 38 percent of the participants saying they felt like the other gender to some degree.

None of these respondents was transgender, Joel emphasizes. Yet both studies revealed a similar percentage of people reporting that “they sometimes wished they’d belonged to the other gender, or wished they had the body of the other sex—sentiments typically associated with transgender individuals or those with nonbinary identities.”

Joel’s studies also confirm that transgender individuals themselves can vary widely in their gender identity. And for that reason, it shouldn’t be surprising that their decisions about whether or not to pursue body modifications can also vary. Yet a conventional wisdom may be arising about that choice as well, she warns. That’s why she points to two studies that conclude that some transgender people may feel more pressure from societal expectations—rather than from their own need—to pursue hormonal or surgical interventions that would align their physical appearance with their psychological experience of gender.

Throughout, the authors tease apart the raw material of nature from the impact of nurture. In terms of nurture, the authors show how the influence of cultural and social norms can begin in babyhood. While all babies, boys and girls alike, express a full range of feelings, studies have found that the people around them can reinforce gender conventions: for instance, by encouraging girls to be “nice” and discouraging boys from crying. Repeated over time, these messages end up harming both boys and girls, placing them in “emotional straitjackets of gender,” they write.

To illustrate the psychological impact of such constrictions, they cite another study, which concluded that college men who felt they needed to continually prove their masculinity experienced more depression and turned to substance abuse more than did men who didn’t feel the need to conform to the stereotype. The takeaway from all these studies is that regardless of gender or sex, no one benefits from being pigeonholed into a category.

As for nature, Joel’s own extensive research has demonstrated that human brains do not come in distinct male and female forms: humans don’t arrive on planet Earth with brains that have been biologically preprogrammed by sets of male or female gender-typical personality traits and intellectual abilities, or a lack thereof. In fact, the brains of male and female babies hardly differ at all at birth, Joel maintains. Even as life goes on, female and male brains are far more alike than not. As for the influence of the three main sex-related hormones of estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, they also overlap in males and females throughout most stages of life.

To be clear, Joel acknowledges that differences do exist in male and female brains—for example, in the typical size, volume, and thickness of different brain regions. But the differences remain insignificant when compared to their overwhelming similarities in wiring and function. Moreover, the authors write, while “no one today would dare use biological comparisons between races or social classes to justify racism or economic status, as was done up to the 20th century,” myths about the deficits of women’s brains are still being used to rationalize discrimination and gender inequality, perhaps most notoriously in the fields of technology and science, but extending to any number of other fields, including business, politics, you name it.

And so we return to what the brain science actually reveals. Joel, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Tel Aviv University, began investigating sex differences in the brain a decade ago, when she encountered research that looked at the impact of stress on the pyramid-shaped neurons in the hippocampus brain sections of male and female rats. Their neurons responded in not two but three separate ways, none of which could be easily assigned as “male” or “female,” a conclusion found in other studies as well.

With her interest piqued, Joel embarked on studies of human brains, using MRIs and other imaging techniques that scan the structure of the entire brain. She analyzed more than 1,400 human brains, examining, measuring, and comparing different brain regions and characteristics. Rather than demonstrating clear-cut differences between male and female brains, the majority displayed a mixture of characteristics.

Joel subsequently conducted another series of studies, these focused on personality and behavior—brain function, as opposed to brain structure—and found a similar result, with men and women showing a mix of what conventional wisdom would dub feminine or masculine qualities.

In none of these studies did Joel find a single person whose profile could be interpreted as entirely “female” or “male.” They were all a patchwork—a mosaic—of traits and features that make us individuals, with our sex and gender accounting for only part of the distinct profile we each possess. That’s the gender mosaic of her title—of which we are all part.

Joel agrees that some of the old gender assumptions are crumbling. We’ve become more aware of the ways such assumptions have, from grade school on, funneled men into “male” math and science professions, regardless of their actual aptitudes, which could well lie in more “feminine” options, such as fashion, nursing, or staying home to care for the kids. Progressive parenting is catching on, too, by adopting gender-free education, avoiding gender labels for toys and activities, teaching parents to let go of gendered expectations for their children, and working with kids to detect and push back against gender stereotypes when they come across them.

All well and good. But before we laugh too much at the erroneous contentions of previous centuries—such as a women’s cranial cavity being too small to house a powerful intellect, or that women who overused their brains risked causing their ovaries to shrivel—it’s important to remember what Lawrence Summers and James Damore had to say in this century. The next time these assumptions rear up in public, Gender Mosaic can provide pertinent facts with which to respond.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.