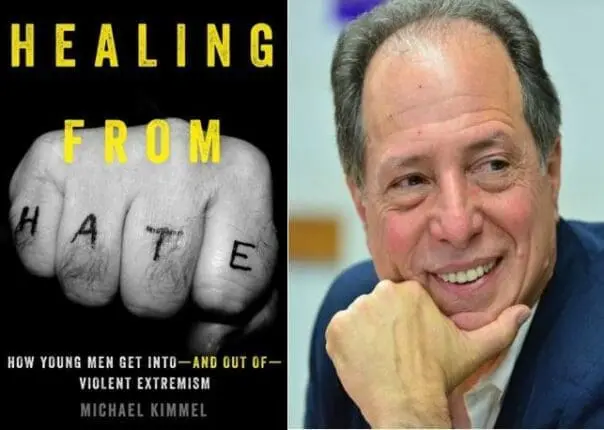

Healing from Hate: How Young Men Get Into—and Out of—Violent Extremism

By Michael Kimmel

University of California Press

288 pages

978-0520292635

In his previous book, Angry White Men: American Masculinity at the End of an Era, published in 2013, sociologist Michael Kimmel captured the emerging zeitgeist of white male entitlement and resentment that Donald Trump would soon tap into. However, Kimmel, a professor of sociology and gender studies at Stony Brook University of New York and director of its Center for the Study of Men and Masculinities, didn’t actually mention Trump in that book. Only later, he writes in an updated introduction to a recently published new edition, did he realize that he’d been focused on a cohort that can now be seen as “waiting for their leader to show up—even if they (and I) didn’t know it at the time.” One can only hope that Kimmel’s latest book, Healing from Hate: How Young Men Get Into—and Out of—Violent Extremism, will prove as prescient as his last in capturing the nation’s mood, this time in the direction of reconciliation.

At the conclusion of Angry White Men, Kimmel wondered whether a way could be found to help turn around the rage and resentment common among the extremist group members he’d interviewed. He soon learned that organizations in the United States, Canada, and Europe were already assisting extremists who wanted to leave hate groups and start over. He went on to interview more than 70 of the former skinheads, neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and jihadists who’d gone through, and in some cases, helped develop these programs. They told him, in detail, about what had first attracted them to their respective extremist groups, how and when they’d decided they wanted out, and which strategies had—and hadn’t—helped them extricate themselves. Healing from Hate is his report. It provides crucial understanding and context for anyone working with clients whose family members or who themselves have become involved with, or are seeking to separate from, an extremist group.

Of particular interest are Kimmel’s lengthy individual case histories. He begins with Matthias, a 34-year old Berliner, the illegitimate son of a hippie mother who’d abandoned him to be raised by her unapologetically pro-Nazi parents. In adolescence, he started going to skinhead parties, attracted less by the neo-Nazi ideology than the free beer, hard-driving music, and instant camaraderie that had until then been elusive for him. With the group, he found a place to belong. At first, the theology seemed secondary. Eventually, though, he became a Holocaust denier, at one point petitioning his high school to hire a speaker to “expose” the Holocaust as a lie.

Expelled from school, he focused on recruiting youngsters to the movement, kids like he’d once been, lost and looking for a place to fit in. He’d groom them by acting as their friendly big brother, inviting them to the kinds of parties that had first enticed him, and impressing them by scuffling with leftists or bullying “non-Aryans” to prove his superiority. But as he approached his late 20s, the routine had grown hollow. One day, as he watched a video of the street clashes he’d once relished, he began feeling guilty for the injuries he’d caused. He looked in the mirror and regretted that he had no meaningful work, no wife, no children—basically no life. He decided to leave the movement.

But a clean exit wasn’t possible. His former friends ambushed him, beat him up, and threatened further violence if he continued to disrespect them by refusing to return to the fold. His grandfather—who’d embraced his becoming a neo-Nazi—cut him off. He had no one else to turn to. But if going it alone was risky, crawling back had far greater drawbacks. So Matthias took a different path. He reached out to Exit Germany, an organization founded in 2000 to aid ex-skinheads who, like him, wanted to find a different way to live.

Trained social workers helped him find safe housing, provided job training, and encouraged him to go to college. He’s now himself a social worker, helping other former neo-Nazis find their way. He’s also in a serious relationship and hopes to have children.

Typical of other stories Kimmel recounts here, this one highlights the ease of drifting into an extremist group, contrasted with the obstacles that impede departure. Additionally, it dramatizes the kinds of support—not just emotional counseling, but also finding a place to live and lining up employment—that’s often required to make a successful transition to life after extremism.

Exit Germany is one of four groups from different countries that Kimmel has chosen to profile. Exit Sweden, founded in 1998, like its related organization in Germany, focuses on former neo-Nazis and skinheads. Life After Hate, based in the United States, was created by a group of Americans who’d left their far-right, white supremacist extremism behind. The final group, Quilliam, sponsored by a foundation headquartered in London, is the only one Kimmel looked at that focused on aiding jihadists who wish to leave the movement.

Each organization offers a slightly different overall approach—which one would expect, given the different countries and cultures from which their members come. That makes the number of similarities that Kimmel has identified among ex-extremists all the more striking—and potentially useful in thinking about therapeutic strategies to help them. The primary factor isn’t just that men account for the great majority of those who belong to extremist groups—approximately 80 percent overall—it’s that being part of such groups validates their masculinity. (He also discusses the women who belong to these groups, many of whom are in relationships with the men, but in less detail.)

In his view, white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and jihadists all share the sense of feeling humiliated and pushed aside. Global economic and social trends have left them behind, along with the jobs, paychecks, and respect to which they felt entitled. In their powerlessness, they find dominion in voicing blame and rage—and often committing violence—against those they target as “other.”

Kimmel has coined the term aggrieved entitlement to describe this toxic mix. It’s paired with a particular worldview that sounds all too familiar. As he writes, “Their politics are reactionary, nostalgic; they seek to ‘restore’ or ‘retrieve’ what they believe they have lost. They look back to create a vision of the future, back to a past that was purer and more responsive to their needs.” It’s a vision that helps validate their own masculinity and that they can celebrate together with their likeminded group members in extremist acts of speech or violence. In concert with their band of brothers, they thus find a way to define themselves as “real” men.

Many of the former extremists Kimmel interviewed came from highly dysfunctional families, were subjects of physical or sexual abuse at home, felt helpless to rescue siblings who were abused, or were targeted or bullied at school. These experiences contribute even more layers of shame to their sense of failing to measure up to a masculine ideal. Kimmel believes that understanding and tapping into this dynamic is essential for anyone seeking to help former extremists.

He emphasizes that rational argument by itself won’t reach the emotional core of identity to which extremists attach their beliefs. Instead, he points out that because most of these men joined these groups in search of a masculine identity, when they leave, they’ll need new ways to feel masculine, whether in a new job or education program or relationship that supports their self-respect.

Some of the organizations helping them have been criticized for not doing enough to counter the racist, anti-Semitic, or other discriminatory beliefs of the former extremists. But Kimmel found that Exit Sweden and Life After Hate regularly employ the so-called “contact hypothesis” to help former extremists unlearn their prejudice as they meet, interact, and work with Jews or immigrants or those of a different skin color. As a result, in the eyes of the former extremists, “others” become transformed from abstract enemies into people with whom they can share interests and whose company they can enjoy. Quilliam’s method for depoliticizing ex-jihadists’ views of Islam emphasizes text-based teaching that pushes back against the ideological interpretations of the Quran used by terrorist recruiters, though it’s unclear how successful that method is.

Throughout the book, Kimmel recognizes the difficulties faced by ex-extremists trying to remake their lives, and he tells their stories with compassion. But there are so many snippets and quotes from case histories sprinkled throughout that they can begin to blur, and because many of these case histories make similar points, the book can become repetitive. Despite these flaws, Kimmel leaves us with an important message. Across the world, prejudice, racism, and xenophobia are becoming more palatable and more mainstream to more people. He’s frustrated by current US government policy to focus only on Islamic terrorism and no longer fund organizations that combat far-right domestic terrorism.

Nevertheless, Kimmel remains hopeful. He believes right-wing populism “is doomed to failure” because it harks to the past, rather than the future. Most of all, he derives optimism from seeing how his interviewees have managed to discard their old views as they’ve learned how to acknowledge the humanity of the “other” while also demonstrating how it takes more courage to renounce hatred than to spread it.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.