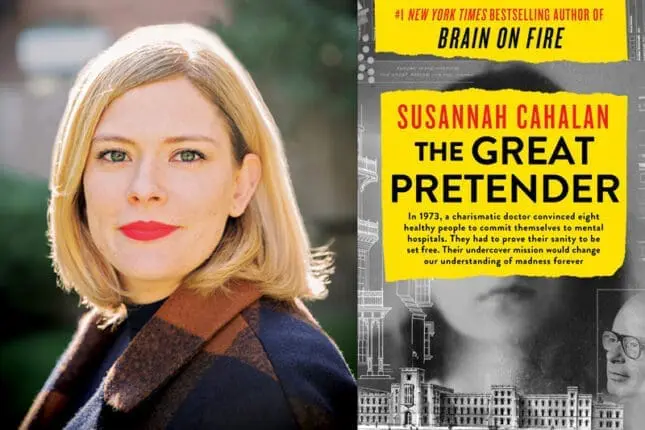

The Great Pretender: The Undercover Mission That Changed Our Understanding of Madness

by Susannah Cahalan

Grand Central Publishing

382 pages

978-1538715284

In 1973, Stanford University psychology professor David Rosenhan made a name for himself by showing how easily psychiatrists could be duped into believing that a group of volunteer patients were so severely mentally ill that they required immediate hospitalization. The study, “On Being Sane in Insane Places,” appeared in the pages of the esteemed journal Science and made an immediate splash. Garnering broad media coverage, it ramped up the public’s underlying distrust of psychiatry and psychology, and helped bolster support for mental healthcare policies whose enduring consequences we still confront today.

Now this study is in the headlines once more. In her riveting new book, The Great Pretender: The Undercover Mission That Changed Our Understanding of Madness, journalist Susan Cahalan uncovers Rosenhan’s study for what it actually was: a fake, whose manifold fabrications had gone undiscovered, until now.

This is certainly not the first well-known experiment to be refuted, but the implications go far beyond the shock value of an exposé. Rosenhan’s methodology was to have eight volunteers (he among them) show up at various psychiatric institutions and report the same symptoms: they heard voices that said, “Thud, empty hollow.” Each was admitted as an in-patient; seven were diagnosed as having schizophrenia, the eighth as suffering from manic-depression.

Their initial deception was accepted without question, but regaining their liberty from the institutions was another matter. Everything the pseudopatients (as Rosenhan called them) did was perceived by the nurses, caregivers, and therapists through the lens of pathology. Their note-taking, which they did to record their experiences for the study, was interpreted as obsessive “writing behavior.” Reading or watching television was deemed solitary and depressive. Everything the patients did confirmed and reconfirmed the judgment that they were mentally ill.

Interestingly, while the real patients on the unit often guessed that these pseudopatients were imposters, the professionals saw no difference. After stays ranging from days to weeks, during which time the pseudopatients were given antipsychotic pills (Rosenhan had shown them in advance how to avoid swallowing them) and therapy sessions, some succeeded in convincing the psychiatrists they were genuinely “in remission,” while others were forced to leave against doctors’ orders.

Rosenhan’s conclusion: “It is clear that we cannot distinguish the sane from the insane in psychiatric hospitals,” he wrote. “The consequences to patients hospitalized in such an environment—the powerlessness, depersonalization, segregation, mortification, and self-labeling—seem undoubtedly countertherapeutic.” His findings were indeed sensational, and even at the time, some critics assailed his research, yet his study remains one of the most widely cited psychological studies of all time.

And now, from Cahalan’s deeply researched book, we learn that the critics were correct to question him. Rosenhan died in 2012, but she tracked down and interviewed many of his colleagues, reviewed his diaries and notes on the experiment, and painstakingly sifted through the unfinished manuscript of the book he’d contracted to write on the study. Despite her extraordinary efforts to identify the seven pseudopatients Rosenhan claimed had also participated in the study, she was able to verify the existence of only one. The others, whose stories Rosenhan had recounted in the study, were almost certainly invented, their stories and experiences fabricated for his own purposes.

Moreover, the hospital experiences Rosenhan had claimed for himself and for the one volunteer Cahalan did identify differed in many details from the stories recorded in the professor’s original diaries and notes. In addition, Rosenhan had claimed in a footnote that yet another volunteer had been excluded from the study because he hadn’t followed the study protocols. Interestingly, Cahalan was able to confirm the existence of this volunteer, yet the actual reason his story was excluded from the study, she discovered, was that his experience in the psychiatric hospital had been positive, even therapeutic; it was his failure to confirm the basic premise of the study that had kept Rosenhan from including him.

Those findings were unsettling in and of themselves. But that’s not the end of Cahalan’s pursuit: she wants to know why Rosenhan’s assertions resonated so deeply at the time. What can we learn from all this about the accuracy of diagnosis in our own time? And what insights can we garner about the dilemmas therapists face today?

Setting Rosenhan’s study in the context of the countercultural attitudes and antipsychiatry movement of the 1960s and 1970s (think R. D. Laing and Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest), she reminds us that the study was sending a message the public had been primed to accept: that the old system of state-run psychiatric institutions and asylums had to go. And with this study giving a further nod to a trend already underway, they did go, leaving in their stead a nightmare of unintended consequences. That’s because additional public funding never materialized to replace the old institutions with anywhere near the needed number of new community-centered mental care centers. The result: our current, dysfunctional mental healthcare system, whose structural inadequacies have consigned tens of thousands of people suffering from mental illness to fend for themselves on the streets, untreated and homeless.

Further, Cahalan grapples with the legitimate questions that Rosenhan’s study, despite its distortions, had brought to the forefront then, and where they remain today. Given our still limited knowledge of the interconnections between the workings of the brain and the course of mental illness, how confident can we really be in the accuracy and integrity of our psychiatric diagnoses and treatments? And what happens if or when we’re wrong?

Cahalan has a personal stake in exploring these issues. In 2009, at the age of 24, she suddenly began experiencing hallucinations, seizures, paranoia, and other physical and personality changes that defied a clear diagnostic answer, even from top physicians at New York’s finest hospitals. One neurologist dismissed her difficulties as the result of being a 20-something binge-drinker, despite her denials that she wasn’t drinking. Another nixed that theory, deciding instead it was some form of epilepsy. Various psychiatrists diagnosed her alternatively as suffering from bipolar or schizoaffective disorder. The only thing all these specialists agreed on was their bafflement at her failure to respond to any of the prescribed antipsychotic medications. They could only watch with helpless dismay as she descended into a catatonic state.

It took an innovative thinker like neurologist Souhel Najjar to solve the puzzle of her affliction: an inflammatory condition of the brain known as anti-NMDA receptor autoimmune encephalitis, which had only been identified in the medical literature in 2007. After a brain biopsy confirmed the diagnosis, Cahalan began treatment that led to a complete recovery. Her first book, Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness, recounted that ordeal.

True, her symptoms had looked so much like a full-blown mental illness that the mistaken diagnosis could be seen on some level as understandable. But hers is not the only medical disorder whose symptoms can present as a psychiatric one. Syphilis or any number of other brain, thyroid, or systemic diseases can also masquerade as, or create symptoms indistinguishable from, mental illness.

But why should it be so difficult to discern the difference?

Looking at her own case alongside the Rosenhan study, Cahalan sees mirror images of the ease with which misdiagnosis can occur, and the damage it can cause. Had Cahalan’s parents not persisted in pursuing further diagnosis, the doctors were already preparing to send her, in her then nearly vegetative state, to a long-term-care psychiatric hospital for the rest of her life. Just how close she came to losing any chance at recovery became clear to her when, after she gave a hospital lecture about her experience, a neurologist introduced her to a patient her age who’d been diagnosed with the same ailment. Unfortunately, this patient’s misdiagnosis had gone undetected for not one month, but two years. That delay in treatment had resulted in irreparable brain damage, rendering this patient unable to care for herself.

Getting the diagnosis right matters. And that’s why the idea behind Rosenhan’s faked study continues to make us uneasy. Rosenhan had set out to question the validity and reliability of psychiatric diagnosis itself. If, as he contended, psychiatrists could be fooled so easily, on what criteria, if any, were they basing their clinical judgments of mental illness?

The publicity engendered by Rosenhan’s study was the impetus needed to jump-start the American Psychiatric Association’s push to revamp and standardize the profession’s diagnostic guidelines. The result was the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (1980). Since then, two more editions have appeared, each the subject of fiery criticisms, many of them still having to do with diagnostic reliability.

That’s not a bad thing, Cahalan believes. “The more we open our eyes to what we don’t know, the more excitement builds in the research community,” she writes. “Emerging studies exploring the link between the immune system and the brain—as is the case for autoimmune encephalitis—have galvanized the quest to understand how thoroughly the body influences and alters behavior, spurring studies of immune-suppressing drugs on people with serious mental illnesses. Researchers have estimated that as many as a third of people with schizophrenia display some immune dysfunction,” and many more studies are in progress.

Her advice is to stay tuned, especially to the promise of neuroscience. What I’d add is to watch out, lest we get carried away by another great pretender.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.