Enjoy the audio version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

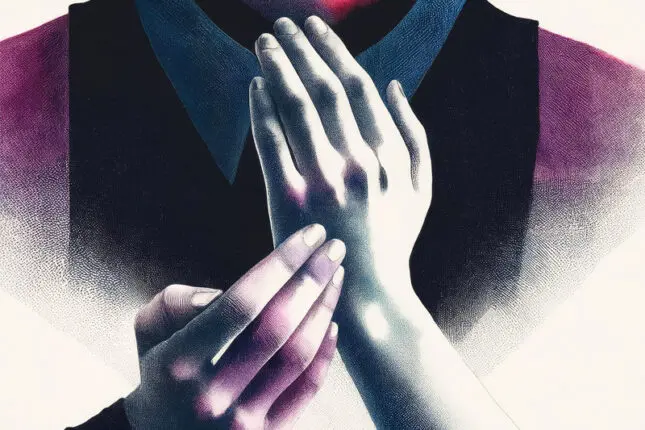

Just minutes into a session with his client Mia, Robert Schwarz does something you won’t see in most consulting rooms. He holds both palms open, as if receiving a small gift, and repeatedly bumps the sides of his hands together. At his instruction, Mia does the same.

“I imagine we could just go straight to telling the story,” Schwarz says. “But why suffer?”

For Mia, “the story” still delivers a gut punch. Even though it happened decades ago, when she was just nine years old, she has a hard time talking about the time her soccer coach cruelly poked fun at her weight while her teammates stood by and laughed. It’s all too much to handle. When Schwarz asks Mia how she usually feels when she thinks about that moment, she hunches her shoulders, shrinks her body, and balls her fists.

“Shame, embarrassment, humiliation,” she says, visibly upset. “I feel like I want to hide and make myself really small.”

“Right,” Schwarz replies, scrunching himself down too in a beautiful but subtle display of attunement. “That sure sounds like shame.” He quickly and deftly pivots. “So let’s take that memory and stick it in a box,” he continues. “Let’s not even look at it.” He pauses. “But if you were to look at it, how would you rank it on a 1-to-10 scale?”

“A seven,” Mia replies.

“So let’s start tapping,” Schwarz says, beginning the hand-bumping. “We’re going to say, ‘Even though I’d have this sense of humiliation and shame if I were to look in the box, I deeply love and accept myself.’”

Mia repeats the mantra.

“Now let’s tap the top of your head,” Schwarz instructs, tapping on his own head with his palm. He slowly moves down his body while Mia follows along on hers. He taps above his eyebrows, then his temples, upper lip, chin, chest, armpits, fingertips, and finally, the back of his left hand.

“Now, close your eyes,” Schwarz instructs. “Open your eyes. Look left. Look right. Hum a tune”—Mia obliges, humming “Happy Birthday”—“and take a deep breath.” It’s a cleansing reset, and Mia’s shoulders relax.

“Now,” Schwarz continues. “If you were to look in the box, at this moment, what do you think the number would be?”

Mia’s response is shocking.

“A one or a two.”

Beyond Tapping

It’s hard to witness what’s just happened between Schwarz and Mia and not think some sort of miracle has occurred. In just 10 minutes, Schwarz has managed to virtually eliminate Mia’s trauma symptoms—at least for now. In this moment, she’s calm, confident, and ready to engage the problem head-on. Now, she can tell the story without getting overwhelmed. But how?

Schwarz says Mia’s response is due to the unique method he’s been practicing for over 30 years, known as the Emotional Freedom Technique, or EFT. It’s a form of energy psychology, or EP, a holistic, integrative approach that views the body as an interconnected system of energy. There are several forms of EP, including Thought Field Therapy, Tapas Acupressure Technique, Comprehensive Energy Psychology, Advanced Integrative Therapy, and Heart-Assisted Therapy, but they’re mostly similar.

Drawing from ancient Eastern practices like acupuncture, each involves tapping acupressure points to release the stress said to be caused by negative thoughts, emotions, and experiences that disrupt the body’s energy. Used alongside cognitive therapy interventions that target distressing thoughts or memories, like focused awareness, mindfulness, and imaginal exposure, proponents say EP can be used to treat a range of issues, including depression, anxiety, trauma, phobias, and chronic pain—and quickly reduce symptoms or eliminate them altogether.

You’d think most therapists would jump at the chance to give their client a sevenfold reduction in symptoms, a surge of confidence, or a foothold to begin the hard work of therapy, as Schwarz did with Mia. But not everyone is so enamored with EP. Detractors have called it a pseudoscience, questioned the integrity of its studies and the objectivity of study coordinators, and say any benefits are due to the placebo effect or the other modalities it incorporates. Some of the biggest criticism comes from therapy purists, for whom all this talk of energy, chakras, biofields, and meridians conjures up the mental image of shamans and spellcasters, not bona fide therapists who follow thoroughly researched protocols and diagnostic bibles.

But EP isn’t just some fringe intervention, proponents retort. It’s been around for nearly 40 years, amassing a wealth of research and success stories along the way. According to the Association for Comprehensive Energy Psychology (ACEP), EP’s leading professional organization, today EP boasts tens of thousands of therapists and has more than 200 published research studies, including 103 randomized control trials, 95 outcome studies, nine meta-analyses, and five fMRI studies. ACEP says these studies not only cement EP as an evidence-based treatment, but place it among the top 10 percent most-researched modalities.

And yet, reads a report on EP published in the journal Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, there are “serious flaws in the methodology of the research. Providers should be wary of using such techniques, and make efforts to inform the public about the ill effects of therapies that advertise miraculous claims.” A report from the journal Clinical Psychologist accuses EP of operating from “an unsupported and implausible theoretical basis.” Clinical psychologist Richard McNally, the director of clinical training at Harvard University’s department of psychology, calls it downright absurd. “We wondered whether it was a hoax,” he writes of Thought Field Therapy, “concocted by some clever prankster to spoof ‘fringe’ therapies.”

This isolated criticism doesn’t rattle EP practitioners like Schwarz. He’s heard it all: that EP is a pseudoscience because you can’t measure meridians (“but you can,” he says), that the energy component is strange (“it’s actually not that strange”), that it only works because it’s similar to other therapies (“most therapies are similar”), or that EP’s studies are flawed (“then why are they all pointing to the same thing?”). But again and again, he says the critics fall into the same trap: “They think about EP too simply,” reducing it to its most sensational components, like tapping. Schwarz says his method is actually rich and multifaceted. And watching the process unfold, it’s hard to disagree.

As Mia continues to tell “the story” over the next 45 minutes, her distress level rises and falls. She shuffles between a variety of emotions: sadness, humiliation, anger, and annoyance. And throughout all of it, Schwarz stays in the trenches with her: mirroring, validating, guiding, and sometimes gently pushing. When Mia says she feels better but something seems amiss in her voice or body language, like a wince or quiver, Schwarz astutely calls attention to it, names it, and asks her to tap and repeat the mantra once again before reassessing her level of distress.

“This is like when you go to the doctor and they ask, ‘Does this hurt? Well how about this?’ he tells Mia. “We just want to get this out of your system.”

Before long, Mia says her distress level is steady at a one. “The anger’s not there anymore,” she tells Schwarz. “I just want to laugh now.”

“Well, let’s keep going,” he replies. “If you could’ve said something to that coach, what would you have said?”

Mia ponders for a moment. “I’d have stood up and faced her,” she says defiantly. “I’d have said, ‘What the hell are you doing?! Why do you need to embarrass me in front of my teammates?! You don’t do that to a kid!’”

Schwarz’s face lights up. “That’s right!” he says. “’You don’t do that! Don’t mess with me!’”

Schwarz’s pride at this bold expression of courage is palpable, but maybe it’s not just the pride that comes from seeing a client reach a breakthrough. Maybe there’s something about an underdog finally speaking truth to power—a classic David and Goliath story—that resonates with Schwarz in this moment. After all, it’s the kind of fight he knows all too well.

Who’s Afraid of the APA?

For energy psychology practitioners, most naysayers are more of a nuisance than an actual impediment to their work and livelihood. But then there are the field’s Goliaths—the large, powerful institutions whose decrees can make or break entire modalities. In the psychotherapy world, few Goliaths loom larger than the American Psychological Association’s Division 12 task force, which certifies treatments as “empirically supported”—and thereby confers multiple privileges and opportunities upon them, not only boosting exposure and solidifying public trust, but opening the door for funding, insurance reimbursement, training and licensure, and research opportunities. Although it’s difficult to quantify exactly how much money flows to methods Division 12 deems empirically supported treatments (ESTs), between federal and private funding, insurance coverage, and public health initiatives, the number can reach hundreds of millions of dollars.

Throughout its battle for recognition, Division 12 has been a thorn in EP’s side. The task force says the modalities on its list of ESTs—which includes CBT, ACT, DBT, EMDR, and motivational interviewing—have undergone rigorous clinical trials and research to determine their effectiveness. Yet despite numerous petitions from ACEP and its allies to get EP added to this esteemed list, with its many research studies in tow, Division 12 has continued to balk.

Tensions came to a head in 1999, when the APA took the unprecedented step of sending a memo to its CE sponsors that singled out Thought Field Therapy as ineligible for psychology CE credit. Before long, the ruling was applied to all of EP, threatening any and all APA CE sponsors teaching EP with the loss of sponsorship status. ACEP appealed the APA’s decision in late 2009, but lost. In response, a handful of ACEP’s allies, including the Energy Medicine Institute’s David Gruder (also ACEP’s cofounder and first president) made a direct appeal to APA President Carol Goodheart in an email sent the following spring.

“The APA has been actively restraining the dissemination of the approach for more than a decade,” Gruder wrote. “As an outside health advocacy group, it is within our purview to publicly challenge a decision regarding energy therapy that negatively impacts public health.” The APA’s stance on EP, he continued, “is inconsistent with its own CE Standards, reflects a disregard of interdisciplinary developments, and does harm to the public.” Evidence of EP’s effectiveness had been mounting, Gruder added, before taking aim at the golden child of evidence-based treatments. “Energy psychology,” he wrote, “is arguably more effective than conventional treatment strategies such as Cognitive Behavior Therapy.”

Twelve days later, Goodheart emailed a response.

“Thank you for writing and expressing your concerns,” she wrote. “I do want to inform you that as APA President I cannot make any changes to the decisions of the Continuing Education Committee.” Pressed by an NPR reporter in 2011 about the snub, an APA representative gave a predictably curt response. “The American Psychological Association does not approve or endorse specific therapy techniques,” she replied. “We therefore have no policy position on energy psychology.” The verdict, it seemed, was final.

But ACEP and its allies continued to gather research, and to appeal. Finally, in 2012, the APA relented and reversed its ban on CE sponsorship for EP courses, noting that the 51 reports submitted, including 18 peer-reviewed randomized controlled trials, met their requirements. EP practitioners were jubilant, and in what seemed like an olive branch, ACEP’s practitioners were even invited to teach at APA’s annual conference.

Sure enough, the APA’s change of heart incensed EP’s critics, who began to question the organization’s integrity. In 2018, clinical psychologist, professor, and scientific skeptic Caleb Lack, who’s devoted his career to studying evidence-based assessment, cried foul over this “failure of the APA” in an article he titled “Energy Psychology: An APA-Endorsed Pseudoscience.”

“There is no evidence to support the existence of the human energy field, the manipulation of such a field, or the channeling of ‘energy’ from one person into another,” he wrote. “These concepts are in direct conflict with all that we know about how physics, chemistry, and biology work.” The APA’s decision, he continued, had been made “despite a complete lack of scientific plausibility,” adding that “as one of the more powerful mental health groups in the United States, the APA’s seal of approval on energy psychology conveys to many people that this is something that works and is widely accepted by the psychological community.” In reality, he wrote, “nothing could be farther from the truth.”

Forging onward, ACEP continued to push for inclusion in Division 12’s list of ESTs, to no avail. Then came a one-two punch: in February, the APA ratified an update to its Division 12 Clinical Practice Guidelines, adding several new recommended modalities for treating PTSD after omitting energy psychology from consideration. And in September, after commissioning a task force to define “psychological treatment,” Division 12 released its conclusion: integrative, somatic, and mind-body therapies—including energy psychology—hadn’t made the cut. A request for reconsideration was denied.

Few can argue that psychotherapy needs rules and guardrails. But Division 12 isn’t just rule-making, EP practitioners argue: it’s gatekeeping. And in the ongoing battle between Division 12 and the EP community, few have been louder about Division 12’s stance than therapist David Feinstein, former faculty at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, an EP practitioner of over 20 years, and the founder and director of the Energy Medicine Institute. Year after year, Feinstein has doggedly sent applications to Division 12, filed appeals, and challenged the detractors in academic publications.

“We sent Division 12 studies showing that we meet the criteria for being listed—again and again,” he says. “We received either cursory responses or no response at all. Meanwhile, APA journals are still publishing articles dismissing EP as a pseudoscience and questioning its ethics. This is misleading and even slanderous toward a legitimate practice, and it’s harming the people who could truly benefit.”

Feinstein is likewise fed up with the APA’s hot-and-cold attitude toward EP, with having his hopes raised and dashed over and over. “In 2003 I said, ‘This year will be the tipping point.’ I said the same thing the next year, and the next. It’s been discouraging to see the evidence repeatedly dismissed—not on its merits, but because it doesn’t fit the institutional mindset.”

Schwarz is equally vexed. “It’s anti-scientific thinking in the name of science,” he says of Division 12’s decrees. “These are the forces who believe anything holistic is unscientific. It’s the medical model. It’s the status quo versus change.”

You don’t just pick up frustration listening to Feinstein and Schwarz, but exasperation. It’s something familiar to any therapist who’s reluctantly flipped through their copy of the DSM or breathed a heavy sigh as they scribbled down a diagnosis code just to get an insurance reimbursement. On some level, most clinicians can relate to feeling hamstrung by psychotherapy’s powers that be, who don’t just determine how we practice, but elevate a select few treatments to an elite status under seemingly mysterious circumstances.

As Feinstein and Schwarz see it, the deck has always been stacked against EP. But with decades of painstaking research and countless testimonials, it seems to be speaking the APA’s language and following all the rules. So why is there still so much resistance?

“To be honest, I don’t know,” Schwarz says. “I can only assume they haven’t evaluated the literature, even though it’s there. If this was a drug, it’d be worth billions of dollars. The research shows EFT works faster, better, and costs less than many other methods. Frankly, if something came along that kicked its ass, I’d be the first to sign up.”

Tapped Out?

Feinstein and Schwarz may have built their careers around energy psychology, but they understand why people are initially skeptical about it. As it turns out, they used to be skeptics too.

“I stumbled onto EP about 30 years into my psychotherapy career,” Feinstein says. “At first, I thought it was utter nonsense. I thought tapping on the skin to resolve major psychological problems was patently absurd. But I kept hearing about how quickly people who used it were reporting strong benefits. So I finally looked into it. Once I embraced it, my practice shifted radically. While the approach can stand on its own, I found that I didn’t have to throw away what I already knew; EP just helped best practices work faster and more effectively.”

“In the beginning, I was very secretive about my interest in energy psychology,” Schwarz admits. “It was the energy, the tapping, the woo-woo.” As a young clinician in the 1990s, he’d been searching for a way to make therapy faster, more effective, and more affordable. After encountering a live demonstration of EFT at a psychology convention, Schwarz knew he’d found what he’d been looking for. But he kept quiet, feeling like the clinical world wasn’t quite ready for it.

“I was struggling with my professional identity and didn’t want to be seen as a flake,” he explains, “so I didn’t tell anyone I was interested.” But behind closed doors, Schwarz continued to explore the method. He attended trainings and slowly began to test it out with clients. The results shocked him. “You’d see change just happen,” he says. “Something would loosen up. The flow of information and energy would shift, and they’d have a totally different take on things.”

Schwarz believed in EFT so much that he even used it with his then-six-year-old son, who became extremely dysregulated after walking through a haunted house attraction on Halloween. “He was flipping out,” Schwarz recalls. “I did a little tapping on him, and 30 seconds later, he was fine!” Emboldened, Schwarz went on to teach EP. Later, he joined the board at ACEP, and then became its executive director, a position he’d hold for 17 years.

Schwarz may be a believer, but he admits that EP needs a rebrand to make it more appealing to more people, contending that the way it was conceptualized and presented to the public 40-odd years ago was flawed. “The language started with the energy and the tapping,” he says. “Over the last decade, we’ve been using less of the e-word and more widely accepted phrases like mind-body intervention.”

Feinstein agrees that perhaps EP didn’t make a great first impression. “Methods like EMDR did research right off the bat,” he explains. “Francine Shapiro did it from the start, whereas EP founder Roger Callahan’s attitude was, ‘Well, you don’t really need research. Just try it. You’ll see that it works.’ His first book, The Five-Minute Phobia Cure, was published before there was a single peer-reviewed study supporting the method. That attitude didn’t play well with the psychology establishment.” Now, with evidence, Feinstein is confident he can sway a sizeable number of therapists on the fence about EP.

“The objection I run into most often is, How could this possibly work?—which was my first impression too. Even therapists who are open-minded and persuaded by the research often assume that EP works because of other factors, like exposure or placebo. I’ve been told, ‘As long as the mechanism seems so implausible, I have to find other explanations for these results.’ My most recent papers offer a compelling neurological model that makes the mechanisms seem entirely plausible.”

Of course, any rebranding will probably have little bearing on Division 12’s blind refusal to accept EP’s merits, Schwarz adds, which doesn’t stem from some particular aversion to EP as much as from a systemic barrier to change. “Division 12 says in order for a treatment to make the cut, it must have been created out of ‘psychological science,’” he explains. “But CBT didn’t come from science; it came from clinical practice. By these standards, you’re eliminating Polyvagal Theory, interpersonal neurobiology, mindfulness, most of behavioral therapy, and anything involving the body. That’s crazy.”

A Change is Gonna Come

You might think that energy psychology is struggling, that it’s destined to live on the outskirts of clinical practice, or that it’s something to be pitied. But in reality, the opposite is true. Culturally speaking, EP is leading the pack. Holistic practices have never been more popular. By 2030, body, mind, and energy healing is projected to become a $395 billion market, quintupling in size. According to a national study published in The Journal of the American Medical Association, more people are seeking out alternatives to conventional mental health treatment because they’re dissatisfied with mainstream options, enjoy the autonomy these methods provide, and see them as more compatible with their values and beliefs. In short, clients aren’t just curious about interventions like energy psychology; they’re asking for them by name precisely because they’re different.

“Lately I’ve been wondering why we’re working so hard to get APA approval,” Feinstein says, “because even without it, EP is finding its way into mainstream institutions, from Kaiser to the VA. It’s also resonating with the culture. Celebrities are talking about how it’s helped them with performance issues or with their fear of heights or flying. You have movies showing tapping. More than 30 countries have used it successfully in post-disaster treatment. I think it’s finally reached a tipping point.”

Clients aren’t the only ones warming up to nontraditional methods. According to a 2024 survey published in Frontiers in Psychiatry, 78 percent of therapists say alternative, integrative, and mind-body therapies like meditation, biofeedback, hypnosis, and yoga are the most promising form of treatment, and most believe that clinicians should receive training in alternative methods. Meanwhile, the National Institutes of Mental Health and Harvard teaching hospitals like Massachusetts General have added alternative treatments to their programming. Feinstein and Schwarz are seeing this same enthusiasm on their end.

“I’ve been teaching EP at the Networker Symposium for years,” Schwarz says. “Early on, maybe 50 people would show up to my workshop. This year, over a thousand signed up. Something is happening. Something has shifted.”

As for the clinicians who feel similarly aggrieved by the dominance of a select few treatments and the exclusionary practices locking others out? They’re speaking up too. Prominent psychologist and ACT cofounder Steven Hayes—whose method even made Division 12’s list—made a bold prediction about the future of EST gatekeeping.

“For nearly 50 years, intervention science has pursued the dream of establishing evidence-based therapy by testing protocols for syndromes in randomized trials,” Hayes writes. “That era is ending.”

Slowly, the tide is beginning to turn. But the hard truth, at least for now, is that Division 12’s dominance and influence will likely continue, and energy psychology will likely continue to fight an uphill battle when it comes to vying for an EST title. Even so, Schwarz isn’t deterred.

“I’m not going to wait for Division 12,” he says. “My goal is to make a difference in the world, to treat the plague of trauma and dysregulation. Right now, a lot of people are suffering who don’t need to suffer.”

Evidence-based treatments have their place. And there are therapists and clients alike who won’t touch therapies that don’t fit the bill. But again and again, studies show that what matters to clients isn’t whether their treatment is evidence-based, but rather the distinctly human qualities of their therapists, like trust, empathy, and genuine care. And nobody—not even Division 12—can accuse Robert Schwarz of not caring.

As his session with Mia winds down, her distress levels are low, and staying put. Schwarz circles back again and again to nip any lingering symptoms in the bud, with empathy, incisive questions, tapping, and mantras at the ready. Finally, there’s only one thing left for Mia to do: say goodbye to the person who’s haunted her for decades.

“Coach was always the first person who came to mind whenever I felt insecure,” she says. “Now I can almost visualize her walking away. If she popped up again, I wouldn’t listen to her anyway.”

“’You’ve been with me for a long time,’” Schwarz says, offering Mia a template. “‘And now it’s time to say goodbye once and for all.’” He begins to tap, and Mia follows along.

“’I’m an adult now,’” Schwarz says, “’and I deeply love and accept myself. You’re not going to haunt me anymore.’” Mia repeats the words. Schwarz takes a tapping hand off his cheek to wave goodbye to Mia’s tormentor, and Mia does the same. A moment later, she smiles softly.

“She’s gone now,” she says. “No hard feelings.”

Chris Lyford

Chris Lyford is the Senior Editor at Psychotherapy Networker. Previously, he was assistant director and editor of the The Atlantic Post, where he wrote and edited news pieces on the Middle East and Africa. He also formerly worked at The Washington Post, where he wrote local feature pieces for the Metro, Sports, and Style sections. Contact: clyford@psychnetworker.org.