Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

Therapists are seekers by nature. Research shows that as a group, we’re driven less by the prospect of material reward than many other professions and more by curiosity about new ideas, the hope of acquiring wisdom, and the desire to achieve deeper self-understanding. No doubt this inclination toward exploring new dimensions of experience has fueled the growing popularity of mindfulness among therapists in recent years. But what exactly is it that mindfulness helps bring into focus that our other theories and methods of therapeutic practice haven’t already addressed? For an answer to that question, we asked Jack Kornfield—Buddhist teacher, psychotherapist, and someone who’s been at the forefront of those helping Westerners grasp Eastern spiritual concepts and practices since the 1970s.

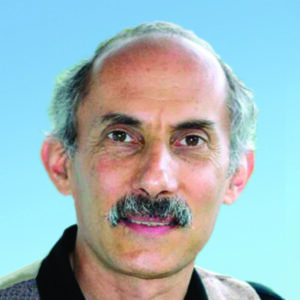

Kornfield himself first went to Southeast Asia to study Buddhism after graduating from Dartmouth in the late 1960s. There he underwent traditional training in the Theravada tradition, sometimes walking five miles a day with a begging bowl to collect food for a single midday meal and practicing long hours of meditation. As part of his training, he even went on a year-long silent retreat. In 1969, he was ordained a monk. After his return to the West, he founded the Insight Mediation Center in Massachusetts and later Spirit Rock in California. He also wrote a series of popular books on meditation practice and worked as a psychotherapist integrating Western psychology with Eastern spiritual teaching.

Kornfield believes that the narrow problem-solving focus of the medical model that informs most psychotherapeutic practice ignores the larger issues that always lie at the edge of the therapeutic conversation. In this interview, he describes how ritual—what he calls the experience of the sacred—and a concern with the larger mystery of our lives can deepen the therapeutic encounter.

***

Psychotherapy Networker: Most therapists shy away from spiritual language, but you like to talk about the importance of creating a “sacred space” in therapy. What exactly is a sacred space, and why do therapy clients need one?

Jack Kornfield: The deep work of the soul requires that we create a place of safety where people feel “Here’s where I can be listened to. This is where I can be held.” Therapy should be a place where they can experience deep repair, forgiveness, and an opening to greater wisdom. When I work as a therapist, I usually start sessions by just saying, “Let’s sit quietly for a few minutes.” I don’t even call it meditation. If people ask for more instruction, I say, “You can feel your breathing, but mostly just be present.” If you don’t help them make some separation from the state in which they walk in, you often just get the road noise: “Somebody cut me off in traffic,” or “I just got a nasty email,” and it’s all superficial. But if you sit together for five minutes and just let things settle, the conversation starts at a much deeper level.

PN: What does recognizing the importance of the sacred and ritual add to the experience of psychotherapy?

Kornfield: Human beings are meaning-making creatures. We need to find meaning, or we’re lost. Part of what I mean by the sacred is that there’s an innate impulse in us to look at the mystery that surrounds us and try to honor it in some deep way. One way to do that is through the ancient language of ritual. That’s something that can get lost when therapy becomes routinized and medical.

When you shake someone’s hand, or when you bow to someone in India and say “Namaste”—which means “I honor the divine in you”—you’re enacting a ritual that goes back to showing that you don’t have a weapon in your hand. It’s a gesture to say, “This is a safe encounter.” Even more, it’s a gesture to say, “I see you. I really see you.”

I’ve worked periodically over many years with Michael Meade and Luis Rodriguez from the Mosaic Multicultural Foundation. They do groups and retreats for kids coming out of gangs and incarcerated youth. If you start a group with kids coming out of gangs by saying, “We’re gonna talk about mythology, meditation, and poetry,” they’ll sit in the back of the room and think, “Man, I live on a street with people walking around with 9 millimeter pistols, and you want to give me a poem and a little meditation?! Come on! Give me something I can use.”

So we might begin with a simple ritual and say, “Before we can have an honest conversation, there are many people in this room who haven’t yet been recognized but need to be included in the conversation. I want everyone here to go out into the parking lot and pick up a stone for every young person you know who’s been killed.” Some of these guys will come back with their hands full of stones. No young person should know that many dead people.

And there can be a table with one lighted candle in the middle of it. And we might say, “When you bring each stone back, place it next to the candle and say the name of the person you’re thinking of. ‘This is for RJ.’ ‘This is for Tito.’ ‘This is for Homegirl.’” By the time they’re done, there’s a pile of stones around the candle. They sit back down ready to have a deep conversation, because they realize this is a place where they can talk about what’s actually going on in their lives.

PN: How can therapists bring more of this dimension of ritual and recognition of the sacred into their work?

Kornfield: Most of us work in offices with fluorescent lights, in a setting that reflects the roots therapy has grown out of. After all, clinical psychology grew primarily after World War II because so many soldiers were coming back shell-shocked, or with what we now know is post-traumatic stress disorder. The response to them originated in the medical model: “Here’s our diagnosis; here’s our treatment plan.” But in fact, our work is probably closer to the tradition of the healers and shamans of every wise culture.

A woman came to see me during a retreat whose specialty was working with people who’ve been tortured. She’d been working with the United Nations, and they were sending her people from Rwanda, Cambodia, Guatemala, Argentina, Iraq, Serbia, and many other countries. As she sat in the retreat, she’d get bombarded by the images of these people and their stories of the way they’d been tortured. So I taught her grounding and cleansing practices and how to sweep her body with light to release the images she saw. We worked with practices to help her clear her body of the pain she was holding. But then I asked her, “What does your office look like? Where do you sit? Describe it.”

She said, “It’s a room. I have a plant there and a chair, and people come in.”

I said, “You need to change your office. On the wall behind you, I want you to put a big shelf. On that shelf, put a Buddha. Next to the Buddha, put Kwan Yin, the goddess of infinite compassion. Put Guadalupe or Mother Mary and a statue of Jesus. Also, put an image of Kali or Durga; you’re definitely going to need her. You’ve got people from Haiti? Put the Haitian gods. Put a page from the Quran on the mercy of Allah. Put a Star of David. Basically, put any god you’ve heard of on there, because you need backup. No individual should hold these stories of torture in their body. They should be held by something bigger. Now when people come into your office, they’ll not only see you, but also who’s behind you. So they’ll think, Okay, I’m not just talking to you. I’m talking to something greater. And at the end of each day, bow to the altar and place all you’ve heard in the hands of the gods.

PN: You have a wonderful way of describing the “mystery” that surrounds our existence. How do you see that mystery?

Kornfield: We’re born into this mysterious human incarnation. Nobody knows how we got here. Look at us: we’re strange! We have eyeballs, these round things in the middle of our heads. We have a hole at one end of our torso in which we stuff dead plants and animals and grind them up and glug them through this tube inside us. And we walk around by falling in one direction, catching ourselves, and falling in the other direction. We even have vestigial claws and tails. It’s bizarre. Then you look around and there’s an amazing sunrise and sunset and huge planets orbiting in galaxies billions of light years away. We’re all here in this mystery. It’s an amazing thing to have a human life.

You can create a sacred space by hanging a picture, lighting a candle, sitting quietly, or reading a few lines of a prayer or a poem. And sometimes we can invite clients to create rituals as part of their own healing process. It might be the ritual of writing a letter to a dead mother telling her everything they’d wanted to say while she was alive but weren’t able to. They could spend a week or two writing the letter, adding more until everything’s poured out. Then maybe they give it to you to read, or you read it out loud together. Maybe they go out to the woods, because the woods are sacred to them, post it on a tree or bury it. Or maybe their mother was difficult, so they make a fire and burn it, releasing them to go on with life. Whether you call it inviting a sense of meaning, timelessness, or the sacred, including the gesture of some form of ritual begins to bring back the shamanic element of what we do.

PN: You’ve become interested in the role of virtue in therapy practice. Could you talk about why you think therapists don’t pay enough attention to the importance of virtue?

Kornfield: We’re scared of the idea of virtue because we’re afraid of overlapping with religion. We want to be sure that no one thinks we’re trying to make somebody religious or impose religious values. We separate church and state, but somehow that can lead us into separating the sacred from healing. So we’ve made therapy into a medical thing and a purely monetary transaction. In doing that, we’ve lost something not only precious, but essential.

In Victorian times, people needed to lift the repression of religious morality so they could talk about their sexual feelings and other forbidden emotions without criticism or judgment, so psychotherapy became a way of lifting the weight of Victorian moralism. But people forget that it’s just the first step. Yes, you want to be able to talk honestly about your impulses and desires and sexual weirdness. You want to be able to admit that sexuality is weird. After all, we make new human beings by licking and touching and inserting one part of a body into another and squirting little tadpole things. It’s bizarre.

PN: That’s so romantic as you describe it, Jack.

Kornfield: It’s fantastic! It’s one of the great gifts because it’s the place where we lose ourselves in love and can touch the timeless and the infinite. It’s magic. It’s wonderful. It’s also strange.

PN: Just as long as you do it by candlelight.

Kornfield: Psychotherapy should be a place where we say, “Let’s deal with what’s true in the psyche honorably and honestly.” But we can’t forget the importance of virtue and morality. One time I was seeing a guy who I learned was embezzling money. He said, “It’s okay; no one will find out.” He had it all worked out.

I said, “But there’s one person who knows beside me, and that’s you. How do you live with yourself? What does it do to your soul?” I didn’t pose it in some moralistic way, but because stealing creates suffering. It inevitably creates paranoia because people have to fear being found out. There’s a reason that human beings in every wise culture have a kind of moral code or a sense of virtue or ethics. It’s because certain things lead to suffering, and certain things don’t. If you steal regularly, it’s likely to lead to suffering. If you lie a lot and you misuse your sexuality, it’s likely to lead to enormous suffering.

That’s really what virtue or morality is about. They’re the operating rules for human incarnation. They lead to happiness and well-being of spirit. When you steal, it’s just hard to sit with yourself. And these are the kinds of things that it’s fine to talk with people about in therapy, not in a judgmental way that adds to their repression, but in an honest and honorable way.

PN: As somebody who’s been instrumental in bringing Eastern traditions to the West, what do you think of the way mindfulness has achieved such remarkable popularity in mainstream culture?

Kornfield: The popularity of mindfulness today is far beyond what any of us original teachers of mindfulness in the West imagined. When I go to major therapy conferences, mindfulness is everywhere. Western psychotherapy is learning a lot from the ancient traditions, but Eastern practitioners are learning from modern trauma work. Whether it’s in the Zen or other Buddhist traditions, or the yoga tradition, there’s the influence of modern psychotherapy. I see this as a really fruitful wedding. Of course, I know that like so much else in this culture, the forces of commercialism take over, and there’s mindfulness taught without the emphasis on ethics and loving-kindness and compassion. But no matter, I trust the whole spread of mindfulness, that it’s good medicine that will help many people find the deeper dimensions of life.

Illustration © Illustration Source / Ludvik Glazer – Naude

Jack Kornfield

Jack Kornfield, Ph.D., trained as a Buddhist monk in Thailand, Burma, and India and has taught worldwide since 1974. He is one of the key teachers to introduce Buddhist mindfulness practices to the West. He holds a doctorate in clinical psychology and is the co-founder of the Insight Meditation Society and of Spirit Rock Center in Woodacre, California. He has written more than a dozen books including The Wise Heart; A Path With Heart; After the Ecstasy, the Laundry; and more.