Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

For as long as I can remember, acting, singing, playing music, and otherwise engaging an audience were all I ever wanted from life. At age 5, I got a part in the kindergarten circus as ringmaster because one of the teachers had noted that I was “loud.” I took it as a compliment. I proudly wore a tuxedo and a top hat, energetically introducing the other kindergartners as they came on stage to perform a clown or animal act. The “chimpanzees” were a big hit, climbing the ropes in the gym with more enthusiasm than skill. When several tumbled to the ground I ad-libbed, “Included at no extra charge!” The parents’ laughter intoxicated me. From that point forward, I was hooked on the thrill of performing.

When I graduated from college with a major in theater and dozens of productions on my resume, I stood in cap and gown among friends who were preparing to go off to graduate school, a teaching career, or a place in the family business. Me? I was off to Boston to realize my dream of becoming the next singer/songwriter who’d change the face of music, even if that meant pounding the pavement as my own agent to get shows wherever I could.

The music business was brutal. Sometimes I’d show up for a gig, guitar in hand, only to greet a club owner who’d claim no knowledge of me. When I did get to play, the pay was minuscule. A Saturday night show might net $15. To make ends meet, I relied for support on the benevolence of friends and my brother, straining their generosity. Still, I wanted it all: a recording contract, adulation, concerts, and more adulation. Yet something barely perceptible was gnawing at me. I was loath to admit it and still focused on my dream, but I was craving a more middle-class stability—a regular income, a comfortable place to live, a more predictable life.

Finally, I succumbed to a day job, a symbol of failure among working musicians. Mine was better than most—working at a copy shop in the shadow of the Prudential Tower—but I was burning out on performing, even though occasional moments of exhilaration compelled me to continue. After a buildup of nerves waiting to hear my name announced from the stage, for example, I’d sprint to the microphone blinded by lights, hear the applause, and feel so good I’d wonder if I was still observing the law of gravity. Occasionally, I’d even play a college concert, the favored gig for every musician. College audiences are bigger, happier, and more attentive than people in clubs, whose main attraction is usually the liquor, not the musician.

It was at one of those revered college shows that I met up with Ted, who was studying there. I’d gotten close with Ted and his father, Rob, years before, when I was working at a summer camp Ted’s family owned. We’d spent many evenings talking together, and Ted and Rob had often listened to me perform. In many ways, I was even closer to Rob, who, despite being a generation older, seemed more like a contemporary than an elder. At the time we were reunited, I learned that Rob was just finishing a PhD in psychology, having gone back to graduate school in his early 40’s, after several ill-fated career moves.

At the college concert that afternoon, I looked out from the outdoor stage onto hundreds of students frolicking on the lawn in front of me, tossing Frisbees in the air, and bumping a giant beach ball in a communal ritual. During one of my songs, a young man from the crowd joined me onstage in an impromptu rendition of “The Letter” by The Box Tops. I was told afterward by a number of people that it was a magic moment, but it didn’t feel magical to me. Something was missing: I felt flat, numb.

When Ted and I arrived back at his home, Rob met us in the entryway, looking very much the career academic in his tweed jacket with patches on the sleeves, crewneck sweater, and longish, slightly unkempt hair, graying at the temples. He may have been late to settle into his career, but it was clear to me that he’d become comfortable in it.

Over home-cooked beef stew, the three of us talked about my life, and I confessed that sometimes being a performer didn’t feel like a legitimate career. As I spoke, I leaned toward Rob. “I just feel like real people don’t do such things,” I said. “They get jobs and raise families. They don’t traipse around with a guitar, playing coffeehouses into the wee hours of the morning.”

As Rob nodded his acknowledgment, he looked at me quizzically. Maybe there was something about my continuing to search for my path in life that reminded him of his own struggles. I could feel the focus of his attention. After dinner, we moved to the den, and I settled into a well-worn leather chair beside the fire. We talked about life, ambition, and the need to contribute to something larger than oneself, a calling that had come relatively late to Rob. Lighting his pipe from a long wooden match, he suddenly asked me, “How long do you think you can do this, Richard? It’s clearly taken a toll on you. I can see it in your eyes.”

Had anyone else said this, I’d have recoiled into defending the identity I’d built and refined over so many years. But sensing that Rob understood my turmoil from some place deep inside himself, I just took in his question and then replied softly, “I don’t know.” After a few moments, however, I blurted out, “Look, this is really all I know how to do. And I think I’m pretty good at it. It’s just that, well, there are so many talented performers out there, and maybe they know people who know people who can help them, or maybe their voices are just better, or maybe—I don’t know. I’m just so alone.”

The fire crackled an uneven rhythm of pops and snaps.

“Don’t get me wrong,” Rob said. “I think you’re great. But this life you’re leading—I don’t know that much about it, but it isn’t for everybody. I don’t have to tell you that there are a lot of casualties out there. Is that how you want to end up?”

I felt a wave of longing envelop me, but I couldn’t quite surrender to it. “It’s who I am,” I insisted. “Who else am I supposed to be?”

Rob drew on his pipe as an impish gleam in his eye appeared. “I’m not talking about who you are. I’m talking about what you’re doing with your life. There’s a difference.”

Strange as it may sound, I’d never really considered that possibility before.

“There’s more to you than just being a performer. You’re overlooking all those other things you might become.”

As I started to respond, he interrupted, raising his hand gently. “Just listen,” he said. “I’m going to give you some money for a plane ticket, round trip from Boston to Syracuse. I want you to go up there and talk to some of my colleagues in the educational psychology department. Take some time to hear what they have to say. I’ll call them to let them know you’re coming.” I sat, dumbstruck, as he crushed the bills into my palm. “You’re lost,” he said. “I understand, because I’ve been lost a few times myself. This trip might be a chance to find yourself.”

I closed my fingers around this totally unexpected gift, staring into the fire. Candles flickered elsewhere in the warm room.

I’m not a particularly spiritual guy, but I feel that Rob entered my life at precisely the right moment, guiding me away from a dream that was on the verge of destroying me—a dream that I didn’t have the courage to walk away from. As it turns out, not all dreams are nourishing ones.

I’m reminded daily in my current job, as dean of students for a large medical school, how spontaneous exchanges like the one I had with Rob that evening can open doors in our lives. The challenge is to recognize these invitations when they come. Over time, I’ve even learned how to keep the thrill of music and performing as part of my life. In fact, my band will be playing soon for the annual medical school talent show. You’re all invited!

Illustration © Adam Niklewicz

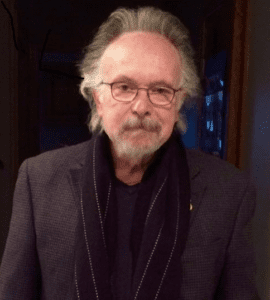

Richard Holloway

Richard Holloway, PhD, is a professor, associate chair of the Department of Family and Community Medicine, and associate dean for student affairs emeritus at the Medical College of Wisconsin. He maintains a practice as a licensed marriage and family therapist.