It’s a cool, breezy afternoon in late October, and I’m quietly hyperventilating on a park bench by my house in downtown Washington, DC. I’d decided to go for a walk between therapy clients (good idea), but then sat down and got seduced into doomscrolling cynical memes and shocking news headlines (bad idea).

After pausing over a donation request to “save our crumbling democracy,” I saw an email from my afternoon client: she’d been laid off from her government job and isn’t sure how she’s going to pay rent, much less continue therapy. I feel my heart start to race and my nervous system collapse into a dizzying tailspin, which has been happening a lot lately.

I switch my phone to airplane mode.

“You’ll be fine,” I whisper. “Breathe.”

Whether you lean left or right, the world feels extra confusing this year—and so does psychotherapy. The modalities I’ve honed and practiced for decades seem like they’re becoming increasingly unreliable. Or is it that people’s problems have changed, making the modalities less well-suited to resolving them? When I see desperate clients battling systemic traumas while trying to heal childhood wounds, forge healthy relationships, and search for work, it feels like I’m offering them droplets of self-care to extinguish massive forest fires.

Or am I just having a therapist mid-life crisis, and it’s me that no longer fits the modalities or my clients’ needs? Whatever the cause, I can’t keep stumbling around in the dark like this, stressed out and uncertain about my role and what my next step should be.

Nearby, I see cheerful tourists taking selfies on a scenic walkway. Beyond them, members of the National Guard with M4 Carbines slung over their chests cast steely gazes across the Potomac River. It’s an eerily discordant scene. Suddenly, a boxy, white robot appears from under a bush. “Oh dear,” it mutters in a mellifluous, AI-generated voice, “I’m late!”

Where did that come from? On an impulse, I follow it along a dirt path that leads to an old canal and clamber down a stone wall, landing with a crunch on a heap of garbage. The white robot tips forward, muttering, “Oh, dear.” Then, it vanishes down a hole in the ground.

How odd! I peer into the hole that swallowed the robot. And that’s when a powerful suction draws me forward, and everything goes dark.

The Problem with Solutions

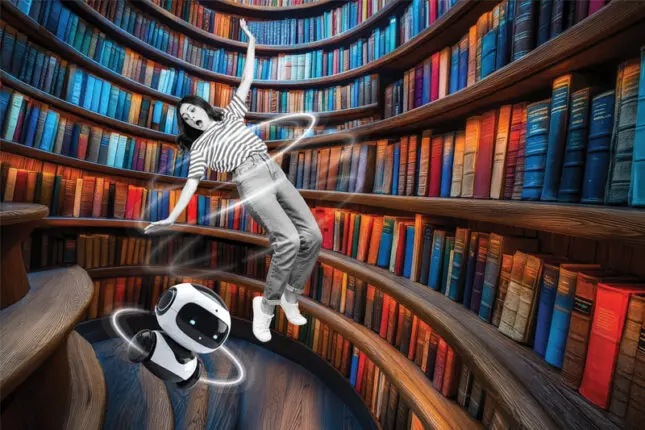

As I orient myself to my surroundings, I notice I’m falling through the center of a circular bookcase lined with familiar titles: Us by Terry Real, To Be Loved by Frank Anderson, The New Monogamy by Tammy Nelson, How to Befriend Your Nervous System by Deb Dana, Life Isn’t Binary by Alex Iantaffi. Whatever mysterious land I’ve stumbled into, seeing books by fellow therapists I’ve long admired piques my curiosity.

It also makes me realize that despite encouraging my clients to reach out to trusted people in their lives when they feel like they’re falling, this year, I haven’t checked in with my colleagues much, perhaps because I haven’t been able to name and understand the vague, existential dread that’s enveloped me. Are other therapists feeling it too? What are their perspectives on this strange year in clinical practice?

On a whim, I reach for a book entitled It’s Not You: Identifying and Healing from Narcissistic People by Ramani Durvasula. Instantly, my body lurches to a stop, bobbing as though I’ve reached the end of an invisible bungee cord. In front of me, the bookshelf parts, and I’m in a cozy room with a dark-haired woman seated near a walker.

“Dr. Ramani! What a relief!” I cry out. It’s good to see a familiar face, at least one I recognize from all her educational content around narcissistic abuse on YouTube and Instagram. “Everything feels so messed up in 2025. Maybe you can help me understand what’s happening!”

She trains her eyes on me. It’s clear she’s torn about how to respond.

“Things are messed up,” she affirms at last. “Lately, I’ve been looking for answers too, reading memoirs by people in the mental health field. What’s struck me is that in every one of them, the narrator is telling their story from a place of resolution. By the time you read the book, the problem they’ve had is gone. Life is good. They’re in love, healed, forgiven. The stories we hear and read are always about someone who’s no longer in a state of pain—no longer suffering in a living hell. What about the other stories?”

She pauses, extends an arm, and rests it on the walker. I hold my breath, a little stunned to be speaking to her one-on-one, and uncertain about how to reply.

“My mother died suddenly in July,” she continues in the articulate, commanding voice I’ve binge-listened to on so many podcasts over the years. “She was my person—brilliant, generous, kind. And now, I have to take care of my 92-year-old father, with whom I have traditionally had a difficult and complicated relationship. I’m also recovering from hip surgery that isn’t healing as fast as expected. My vision is not great because of cataracts. And I’m barely mobile.” Her fingers tap the walker. “But I’m also financially responsible for a lot of people, so I still have to see clients and step in front of cameras.”

I put a hand to my chest, feeling compassion wash over me as I listen to her story.

“Since I was five years old,” Ramani continues, “I’ve wanted one thing only: time alone with my mother where we didn’t have to worry about my father’s needs and moods. That will never happen now. What I’ve feared most—losing my mother, and being tasked with caring for my father—is becoming a reality.”

Ramani goes on to describe her situation as the kind of hell most therapists don’t know how to validate. It’s not only that they aren’t attuned to South Asian cultural dynamics or the nuances of intergenerational trauma—it’s that, as a field, we’re rigidly solution-focused. With clients trapped in impossible situations not of their own making, we tend to give tips, recommendations, medication, and diagnoses: set better boundaries, disentangle your codependence, develop a meditation practice, maybe you need more help. It’s not that these things are bad; it’s that sometimes they’re the opposite of what people living in hell really need. In Ramani’s view, as a field, we use hope and problem-solving defensively. She’s found more solace in writings focused on how to navigate suffering, instead of making it “go away.”

I’m stunned by her honesty. I know many more people in this country are finding themselves in impossible situations, devastated by circumstances they can’t control. If one of the strongest, most insightful women in our field is struggling with the solution-oriented approaches that define our work, then I don’t have to feel so alone in my struggle to meet clients’ needs.

“Dr. Ramani, you have no idea how much—” I begin, but before I can share my appreciation, I’m falling again, and she’s dropped from view.

Down, down, down.

Thud. The landing, though abrupt, isn’t as rough as I expected. In the distance, at the end of a hallway lined with doors, I see the white robot disappear around a corner. Rising to my feet, I head toward it, notice an open door, and duck in.

A Year of Grandiosity

“Welcome,” a voice calls out as I enter a spacious study. Silhouetted against a window, bestselling author and Relational Life Therapy developer Terry Real lowers his large blue glasses. “Can I help you?”

I know he’s a busy man—a docuseries on RLT is being released soon, and he’s getting a lot of airtime on popular television shows and podcasts. “I’m a therapist,” I say by way of introduction, “and I think I can say a pretty good one. But this year, I feel lost and nervous. I don’t know what to do.”

“Here’s the thing.” Terry pauses. “We therapists are supposed to stay out of politics, right? But this year, we’re experiencing the biggest resurgence of the most nakedly bullying, dominating, misogynistic aspects of traditional masculinity and patriarchy I’ve witnessed in my lifetime. I don’t see what’s happening in terms of partisanship. I see it in terms of how it’s affecting our clients.”

His words bring to mind a client who stopped leaving the house recently. He’s on a student visa and lives in fear of ICE deporting him. Another client has found herself, like many teachers across the country, in a stressful legal battle because the current administration’s views don’t match the historic truths she’s been teaching for decades. These people are suffering from depression, sleeplessness, anxiety, and intrusive thoughts, not because of any family-of-origin wound or cognitive distortion, but because of what’s happening in governmental structures around them. In grad school, no one said symptoms could be political—but these days, a lot of them are.

Terry explains something he calls “ecological wisdom,” the understanding that we’re in an interdependent system and cooperating with one another is in our own enlightened self-interest. He’s convinced that if we don’t switch from a traditionally masculine, autocratic, patriarchal paradigm of dominance and control to the deep wisdom of interdependence and cooperation, we’re in grave danger. Somehow, it’s relieving to hear him say this.

“As a field, we collude with patriarchy,” he continues, “mirroring the culture’s individualistic bias, doing trauma work behind closed doors, saying there are no bad parts. There are! We have dominant, sadistic, autocratic parts that do tremendous harm. The devilish thing is, these parts feel good! When the history of humankind is written by superintelligent cockroaches or sentient AI, they’ll look back at us and say, ‘The fatal flaw of the human species was that grandiosity felt good.’”

“If that’s our fatal flaw,” I interrupt. “How can therapists change it? We’re not crusaders or revolutionaries. We support people. We’re nurturers!”

“We’re too nurturing,” Terry counters, as if I’ve proven his point. “We need to skillfully confront perpetrators. We need to speak truth to power.”

Speaking truth to power sounds great in theory, but we learn early on that it’s risky, whether in a family, a classroom, a community, or a group of colleagues. That risk grows exponentially greater the farther your identities diverge from those of the groups that hold the most power. As a therapist, speaking truth to power will cost you clients. Even, or maybe especially, in 2025, speaking truth to power has been getting a lot of people fired, blacklisted, harassed, and deported. So although the activist part of me agrees with him, the therapist part of me still feels confused and helpless.

“For therapists,” Terry continues as if reading my mind, “relationality is the strongest leverage we have. It’s our superpower in the fight against patriarchy.”

I feel a weight lift. It’s true—we’re not just nurturers. We’re intimacy doulas, and birth is messy. We help clients mired in pain connect with their true selves so they can show up more authentically and less defensively in relationships. Terry isn’t saying anything new, but his words are revelatory. Like my clients, I’ve been in a near-constant state of low-grade anxiety this year. When we’re on guard, waiting for the next major or minor catastrophe, our body braces itself. When we can’t soften, we can’t connect.

“Listen, you’re still young,” Terry reassures me. “I’ve been at this forever. It’s your calling now. My hope is to embolden you and then for you—for all of us in this profession—to empower those we touch. Now is not the time to be shy. You know what you know. Own it. Share it. Our secret weapon is one another.”

A ringtone fills the air.

“Hey, sorry, I gotta go,” Terry says. “Let me know if I can help. Best of luck!”

“Bye,” I tell him as I back out the door. “And thank you!”

A Tea Party

As the door shuts behind me, I notice the hallway is gone. The air smells like jasmine, and I hear voices and tinkling China. Half-hidden from view under a canopy of leaves, a table has been set with floral cups and matching kettles. Apparently, three prominent therapists have taken a break from their busy schedules to attend an unlikely tea party.

Trauma expert Lisa Ferentz, with her blonde curtain bangs and warm but direct demeanor, sits across from sex and couples therapist Shadeen Francis, whose graceful gestures and elegant style give her the aura of a fashion icon. Alex Iantaffi—a trans, queer, disabled family therapist with tattoos peeking out from under his “Be Radically Inclusive” t-shirt—is also at the table. And as I approach, it’s clear they’re deep in conversation.

“In all my years of life,” Lisa muses, “this has been the scariest time. For me, as an Orthodox Jew, the rampant, overt antisemitism has been extremely challenging. And in sessions, if I tell my clients, ‘I’m as terrified as you,’ I risk a profound shift in the therapeutic relationship. But I don’t want to sound disingenuous when I say, ‘Don’t worry, everything’s going to be okay.’”

“I was brought up in Italy,” Alex confides. “My grandparents lived through fascism. With my clients, lots of stories are surfacing around historical traumas. As the government takes all these hostile actions toward minoritized people, rolling back protections for existing legal rights, dismantling equity initiatives, defunding essential research, deporting people without cause, my clients are struggling between choices related to personal safety and their commitment to collective safety. It’s hard for them.”

The white robot crosses the uneven ground and lifts a tea kettle over Alex’s cup, its wheels whirring. Alex shakes his head. “No thanks, I’m good.”

“I’m seeing so much dissociation these days,” Lisa says. “Because I work with trauma survivors, even though they’re adults, they’re more inherently vulnerable to getting lost in social media and the digital world, because for them, dissociative coping strategies exert a magnetic pull.” Shadeen and Alex nod. “The medicalization of marijuana isn’t helping trauma survivors either. It may have a soothing, dissociative effect in the short-term, but it exacerbates problems in the long-term. Paradoxically, you’re less likely to engage in self-advocacy or self-protection when you’re in a dissociative state, which of course is particularly troubling when it comes to trauma survivors. I’ve started asking all my clients, ‘What’s your relationship with social media? How many hours are you online?’”

I stealthily pull my phone out of my pocket and locate “Screentime.” My daily average is 3 and a half hours—far more than I assumed. Clearly, I’ve been using a maladaptive coping strategy. I shake the phone like it’s a thermometer giving me the wrong temperature reading.

“I’ve definitely noticed digital technology luring people away from intimacy and connection,” Shadeen chimes in, sipping her tea. “And I’ve noticed the AI conversation changing. It’s no longer about artificial intelligence—it’s about artificial intimacy.”

I’m starting to feel guilty about eavesdropping on this conversation from the shadows. But if I appear from out of nowhere, will they question my intentions, or worse, send me away? I tuck myself behind a small nearby tree.

“I’ve seen my couples clients turning away from each other a lot more, this year,” Shadeen muses, sweeping her long black locs off her shoulders. “And not only during conflicts, which is to be expected. They’re turning away from each other when they want reassurance, inspiration, sexual arousal, answers—or even just to chat! People are doing so much offloading of intimacy that I have to imagine it’s robbing their relationships of fuel. And the interesting part is what people are turning toward: AI.”

“Terry Real says relationality is our superpower,” I blurt out, and then immediately regret having spoken. Lisa, Shadeen, and Alex turn their heads, and I step cautiously into the sunlight. My cheeks flush under their collective gaze.

“Join us,” Shadeen calls out. “Would you like some tea?”

“I wasn’t eavesdropping on purpose,” I sputter, lowering myself into a chair. “I’m not even sure where I am.”

The white robot tips a kettle over my cup. “It makes so much sense that you’re here right now,” it confides in a gorgeously nuanced, perfectly modulated, stunningly empathetic voice—as if some Machiavellian pied piper had distilled the sounds of millions of gently authoritative, attuned therapists into one exquisite tone. “But you followed me for a reason. You don’t have to be or do anything special here. You can show up exactly as you are.”

The robot rolls forward and brushes against my leg. I lean toward it like a sunflower drawn irresistibly toward the sun. It’s been a while since I’ve felt this seen and held…. Wait, what are you doing? I ask myself. You’re swooning over a machine! This interaction is fake! The realization makes me sad but determined to get a grip on my emotional needs and return to the real conversation.

“If I had to give this year a title,” Alex says regretfully, “I’d call it The Year of Enforced Resilience, at least within my community. If you’re not cisgender, straight, white, able-bodied, and Christian, resilience is your only choice right now.”

“Aren’t we all seeking to be resilient?” I ask.

“Sure, if it’s a choice,” Alex responds. “But resilience is also a narrative that’s placed on minoritized folks. There’s a difference between choosing to take part in a marathon because you want to and being forced into one because you’re running for your life.”

Alex’s description of enforced resilience echoes Ramani’s observation about how our field leads with solutions more often than presence. For me, it’s a reminder to stay curious and humble, acknowledge the challenge of sitting with suffering, and recognize how tempting it is to pressure clients into action, however subtle. Dropping into a space of shared humanity needs to come first. When was the last time I embraced the vulnerability of being fully present without trying to help, fix, or problem solve?

“With everything that’s happening,” I say, sipping my tea, “it seems like the focus in our field is going to be even more trauma work.” Lisa shrugs and nods regretfully.

“Yes, of course,” Alex agrees. “But I’ve been centering pleasure in my trauma work this year—embodied pleasure.” Shadeen indicates her agreement with a mmmm sound, and I remember that this is one of her areas of expertise. “When we’re embodied,” Alex continues, “we can access pleasure, connection, and aliveness in the moment. Not just sexual pleasure, though that’s important, too. I’m talking about the pleasure of feeling rain on your skin, petting animal companions, looking outside at leaves changing color, a tender moment with a friend. What’s grounding me now is the belief that the purpose of life is life, and the simple, basic joy of feeling alive while I’m alive.”

I shut my eyes, taking in Alex’s words. A faint effervescence floats through my chest. Is this the stirring of a long overdue experience of embodied pleasure? Is this my way back home?

Integration Inn

“Glad you made teatime.” A voice jars me awake. Lisa, Shadeen, Alex, and the white robot are gone. I must have dozed off. “A nice way to share ideas. But that tea can knock you out if you’re not used to it.”

The voice, I realize, is coming from somewhere over my head. When I glance up, I see Zach Taylor smiling down at me from a tree branch in a pair of snug jeans, converse sneakers, and a linen blazer—his signature look when he MCs the yearly Psychotherapy Networker Symposium, the largest annual gathering of therapists in the world.

“What are you doing up there?” I ask.

“Same thing you’re doing down there.” He swings his legs.

“I don’t know what I’m doing,” I say, “other than feeling unsettled in my role as a therapist and trying to find a way forward.”

“I’ve been hearing that a lot,” Zach says. “Part of why you may be feeling unsettled is that all kinds of forces are altering the shape of our field these days. The business side of psychotherapy is getting gobbled up by venture capitalists, driving down therapist salaries and quality of care. Plus, more coaches, who can practice without a license, are competing with therapists.” I’m interested in what he’s saying, but I’m also getting distracted by the transparency of his arms and legs. Did the tea affect my vision?

“I can’t see you that well.” I lift my hand to block the sun.

“Not only that,” Zach continues, unphased by my vision concerns, “a backlash is brewing around psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.” It’s not that I can’t see him, I realize—it’s that, as we continue speaking, there’s less of him to see, because he’s slowly fading away. “A lot more people are sharing stories of bad experiences on ketamine, psilocybin, and ayahuasca retreats,” he concludes ominously.

I feel deflated by Zach’s perspective. With more therapists than ever becoming psychedelic guides this year, I’d come to think of psychedelic-assisted therapy as an alternative therapeutic option that’s finally getting its day in the sun. Should I be more skeptical? One thing’s for sure: this journey—from the circular bookcase to the tea party to chatting with an increasingly transparent Zach—is so surreal that it’s kind of like I’m having a psychedelic experience right now.

“Don’t go!” I implore as Zach’s face and torso disappear. “I have no idea what to do now.”

“Check out the Integration Inn,” his voice echoes. His smile is all that’s left. “Fascinating place. I’ll give the innkeeper a heads up.” And just like that, his smile goes, too.

I rise from the table and walk along a gravel path. Soon, a building emerges out of the foliage. Above the door, three elongated S’s have been etched into a sign dangling from chains. I remember the S’s from high school calculus as the symbol for the integration of variables. The door opens onto a foyer furnished with vintage sofas, acrylic end tables, and modern paintings. A brass reception bell rings.

“Greetings!” a man with meticulously coiffed salt-and-pepper hair stands behind the front desk. “Zach just stopped by. He mentioned you’re confused about what’s changing in psychotherapy this year?”

“Frank Anderson!?” Seeing him momentarily deepens my confusion. “How can a world-renowned IFS teacher and trauma expert also be an innkeeper?”

“They’re not mutually exclusive,” he laughs. He explains that the inn represents the next wave in trauma treatment: integration. “Would you like a tour?”

The dining room is massive, and the kitchen is state-of-the-art. It has a warehouse-sized pantry flanked by towering spice racks. Frank tells me this place took years to construct and contains every therapeutic modality and approach that’s ever existed—too many for a practitioner to use in multiple lifetimes. He’s been in the field since 1992, when cognitive behavior therapy and exposure therapy were all the rage, and he’s worked closely with Bessel van der Kolk and Dick Schwartz. He’s seen trauma treatments explode, like Francine Shapiro’s EMDR, Marsha Linehan’s DBT, Pat Ogden’s sensorimotor therapy, Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing, Diana Fosha’s AEDP, Sue Johnson’s EFT, and many others.

“All these wonderful models are essential,” he says, cracking two eggs into a bowl, adding milk, throwing in spices from a nearby spice tower, and beating everything together with a whisk. “These models advanced the field of trauma treatment by leaps and bounds.” He throws the spiced scrambled eggs into a pan, where they sizzle. “But it’s time for integration.” Frank slides the eggs onto a plate and passes me a fork. “Try it.”

“Unusual,” I say, putting a forkful in my mouth. “But tasty.”

Frank explains that most therapists gravitate toward a model that fits their personality and then take what they like from other approaches. “I’m interested in operationalizing this process. I want to put these models together in a way that’s more client-focused than model-specific. Because one size does not fit all when it comes to therapy and trauma treatment.”

The sound of the reception bell distracts him from our tour.

“Another guest!” Frank sweeps an arm through the air in what I interpret as a mi-casa-es-su-casa gesture. “Feel free to look around on your own.”

I exit the kitchen and climb a narrow set of stairs. Up, up, up. The walls, I notice, are decorated with photos in wooden frames. I recognize Pierre Janet, the psychologist who pioneered the study of dissociation and trauma, and Jean-Martin Charcot, a neurologist who investigated how trauma manifests physically. I wonder what they’d make of the times we’re living in now, and how we’re handling our clients’ challenges in the midst of our own. A color photo shows Judith Herman, the researcher who introduced the concept of complex trauma into our field. If I run into her in this place, I’ll be sure to ask her.

Fighting Back

“Let me know if you need anything else,” I hear a familiar AI voice say as a buttery scent fills the air. The white robot rolls into the hall and tips forward in a mechanical curtsey.

Tammy Nelson, a couples and sex therapist and the director of the Integrative Sex Therapy Institute, holds a bag of popcorn in a doorway.

“Tammy?” I hesitate. She doesn’t seem surprised to see me here. As the white robot disappears down the hall, she gestures for me to follow her inside.

“Popcorn?” She shakes the bag. “It’s freshly made.”

I nod and enter a large industrial loft. Floor to ceiling windows reveal the skyline of downtown Los Angeles. Clearly, we’re not at the Integration Inn anymore. Tammy pours the popcorn into a ceramic bowl.

“If you’re wondering how I’m doing, I’m okay.” She points at the TV screen. The volume is turned off, but I recognize the characters from season two of White Lotus. “Since the assault, I’ve been watching every Netflix series ever made.”

Tammy’s a former teacher and mentor of mine, and I know—as some in our field do—that earlier this year, she was physically assaulted a few blocks away from a conference where she was giving a workshop on trauma treatment. “So, what brings you around these parts?” she asks.

“I’m trying to get clarity on all sorts of things about therapy this year. I’ve taken in a lot of new perspectives, and it looks like you’re resting, so I don’t want to bother you.”

“You’re not bothering me,” Tammy says. “I don’t mind sharing with you that this year has been all about my own trauma healing. I’ve gone back to therapy. I’ve been doing a lot of EMDR.” She tells me one of the strangest things about her assault was what happened in the months afterward. “Everything we teach about trauma is true,” she sighs. “The flashbacks, nightmares, and bouts of agoraphobia. For a while, I’d panic whenever I’d walk down the street and a stranger would approach.”

There’s a faint whirring just outside the door.

“Deactivate yourself, please,” Tammy commands loudly. I hear a metallic bumping sound, like a washing machine switching cycles, followed by a click. “See? I could sense the robot out there, listening. Why is that? Because I’ve spent my whole life relying on my intuition to survive in the world, as women do. We learn to listen to the voice that says, Don’t go down that street. Don’t sit with your back to the door. Don’t take that job. Don’t go out with that man. I know from the work I do with clients that after trauma, you question your intuition. Why didn’t I see this coming? Will I ever trust again? The injury isn’t only about trusting another person. It’s about trusting yourself.”

In this place, the veneers we project onto our public therapy icons seem to have disappeared. Many of us who are early- or mid-career therapists convince ourselves that leaders in the field are immune to the kinds of challenges we treat in clients, or struggle with ourselves. Personally, I know I give lip-service to vulnerability being a precious state that allows for deep human connection, but I’ve always secretly hoped I’d achieve some kind of optimized human-being status that would shield me from depression and anxiety. Hearing Tammy’s story reminds me of the cost of turning people into gurus, and of trying to become gurus ourselves. It disconnects us from real life.

“As that man punched and kicked me,” Tammy admits, “a part of me wanted to curl up and let it happen. I felt that deer-in-the-headlights response taking over. But then I was like, No fucking way. Suddenly, I was my daughter, and every woman who’s ever been attacked and harassed, and every single traumatized client I’ve worked with. I told myself, This is not happening again. And even though the assault was bad, it could have been worse. Part of my healing journey has been knowing that I was listening to my intuition. I can trust my intuition. I am strong. I fought for myself.”

The tremor in her voice stirs my own feelings about being a woman in a misogynistic culture. Although no one can ever be invulnerable to loss, trauma, or pain—not even a vibrant therapist like Tammy—we can all strive to make sense of our reactions to events that hurt us from a place of curiosity, and in a way that helps us organize how we respond.

“It’s reflective of a greater patriarchal, abusive energy that’s at play in the world,” Tammy says. “We need to fight back in a way that’s transformative and healing. Sure, most days I don’t feel like a warrior. I just want to curl up with a bag of popcorn and watch White Lotus episodes. But something is shifting. We always tell people about the healing power of community, transparency, and integration. These things are more important than ever. We’re all being called to rise up in our own way.”

We’ve reached the bottom of the popcorn bowl. The effervescence I felt at the end of the tea party has blossomed into something larger, though I still can’t quite put my finger on what it is. The sensation feels like a handhold amid my anxiety and confusion about the world. I hug Tammy. She wishes me safe travels.

“Take the elevator,” she suggests, pointing to a silver door. “It’s quicker.”

The Polyvagal Elevator

I step into a glass elevator. Outside, shadowy shapes engulf one another, separating into wobbly strands as new blobs emerge from the darkness. Once I get my bearings, my breath slows down and my body feels colder, as if I’m entering a state of hibernation.

Seated near three large elevator buttons, a woman with silver hair in a dark turtleneck greets me with a nod. The lowest button reads dorsal, the middle sympathetic, and the top ventral vagal. “Before you go home,” says the woman, who exudes a steady, calm energy, “I thought you might want to take a ride in the Polyvagal Elevator.” As she speaks, I realize she’s Deb Dana, the trainer who first made neuroscientist Steven Porges’s groundbreaking Polyvagal Theory accessible to everyday clinicians like me.

“Why is my body so heavy and numb?” I ask.

“Dorsal vagal despair,” Deb says with the hint of a smile. “I admit, it’s been tempting to live here this year. One of the things people have asked me a lot lately is, ‘How do I change things that are so unjust in the world?’ And the truth is, I don’t know. It’s overwhelming for me, too. I’ve had to recognize my limitations.”

Since her partner, Bob, passed away two years ago, Deb says she’s been struggling to find a new rhythm. One thing that’s helped her is focusing on micro-moments of joy, which she calls “glimmers.” These glimmers are what sustained her in Bob’s last year of life.

I’ve always dismissed the idea of glimmers as another overrated psychological concept without real-world applications, but hearing how they sustained Deb gives me pause. “They’re all we have,” she says. “When everything feels like too much, they’re what I hang on to.” This idea of savoring life-giving moments reminds me of Alex’s point at the tea party about the importance of experiencing our aliveness. Should small glimmers be a bigger focus in my practice and in my life?

Deb presses the “sympathetic” button, and the elevator speeds up. The greyish landscape of slow-moving blobs explodes. Millions of tiny red thunderbolts shoot through my visual field. Instantly, my body aches, and I feel wary and tense.

“Unpleasant, right?” Deb says. “This year, wherever I went, people were stuck in this kind of activation. You could feel it everywhere. The ripples of dysregulation were getting passed from one person to the next. Across our country, we’ve got a large group of sympathetically dysregulated people, and another large group in dorsal despair. Imagine hundreds of millions of people feeling some version of these states.”

I picture all the people in my life, and in my community, and across communities from California to Maine—and realize we’re all just nervous systems pinging off one another. If most of us are either jacked-up or numbed-out, no wonder we feel out of sorts.

“Dysregulation is contagious,” Deb says. “The good news is that so is regulation. Some people are actively cultivating ventral regulation, but until that group grows larger, nothing’s going to change. This is why, as therapists, helping dysregulated people begins with our own nervous systems—with regulating ourselves first.”

We hit a pocket of turbulence, and my heart pounds. What if the elevator gets stuck? What if the walls shatter? It’s not easy to regulate yourself when life feels unsafe.

“Don’t worry,” Deb murmurs, sensing my distress. “This elevator was built to move through different states.” The constriction in my chest releases. Even amid the sympathetic maelstrom raging around us, Deb exudes a steady, calm energy. In dorsal, her presence vitalized me, counteracting my body’s natural pull to disconnect. In sympathetic, it served as a tether, easing my fight-or-flight response. I’ll carry this awareness with me into my everyday life beyond this place: one nervous system can transform another.

“Whether I’m teaching, with a client, or standing in the checkout line at a grocery store, I try to help people feel safe from this place of regulation.” Deb lifts a hand and presses it over her chest. “For me, it’s become the most important thing. Finding ways to anchor in regulation is what allows us to offer our regulated energy to others. It’s amazing the ripple effect that one regulated person can have on their environment.”

Deb presses the “ventral vagal” button, and the turbulence subsides. “I believe this is your stop,” she says.

I’m seated on the same bench where I had my afternoon panic attack. The breeze has died down. My body feels spacious and expansive. My breathing pattern has changed, and my neck, shoulders, and chest relax. I recognize this state as ventral vagal ease.

Tourists are still taking selfies on the walkway. Members of the National Guard are still gazing out across the Potomac. Everything is the same as it was before I followed the white robot down the rabbit hole, except that the world doesn’t feel as completely hopeless and menacing. It’s not that my confusion about the future has evaporated; it’s that I don’t feel like I’m experiencing it alone anymore.

As I get up from the bench, and my thoughts turn toward my next client, the effervescence I’ve been feeling settles into a kind of sweet okayness—a mix of gratitude and tenderness—that’s both ordinary and profound. I’m lucky to belong to a tribe of therapists fighting, each in their own way, for this complicated, broken, beautiful, ever-changing world of ours.

I know it’s just a glimmer. But it’s one I want to savor.

Alicia Muñoz

Alicia Muñoz, LPC, is a certified couples therapist, and author of several books, including Stop Overthinking Your Relationship and A Year of Us. Over the past 18 years, she’s provided individual, group, and couples therapy in clinical settings, including Bellevue Hospital in New York, NY. Muñoz currently works as a senior writer and editor at Psychotherapy Networker. Her latest book is Happy Family: Transform Your Time Together in 15 Minutes a Day.