Back in 2018, when we first dedicated an entire magazine issue to exploring the idea of psychedelic therapy, it felt fringe. In citing the research and explaining how psychedelics could open up the human mind, we felt we were either preaching to a choir of clinicians who’d come of age in the 1960s or pushing hard on an envelope that the clinical establishment had sealed and declared off-limits to reputable, law-abiding therapists. Now, we’re in a very different place. It no longer seems necessary to convince people that psychedelics can be both safe and transformational: the therapeutic benefits are well documented, in scientific journals as well as in everyone’s newsfeeds. Attendance at the Psychedelic Science Conference in Denver last year more than quadrupled since the last time it was held in 2017. Increasing numbers of celebrities—NFL quarterbacks, famous actors, British royalty—have been speaking up about the ways psychedelics have helped them heal from conditions as varied as traumatic brain injury and chronic grief. The convergence of psychedelics and mental health appears to be all but inevitable—not a matter of if, but when.

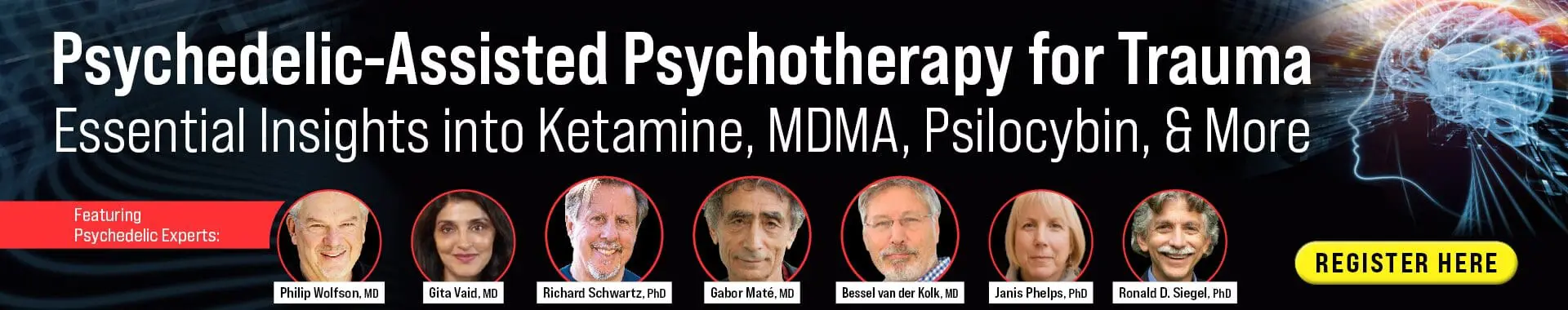

True, it seems we’ve been teetering on the cusp of legalization for at least half a decade. MDMA received breakthrough status a few years ago, and went through phase one, two, and three of clinical trials. The Oregon Health Authority licensed psilocybin-therapy clinics in the summer of 2023, creating, in the process, a whole new profession known as “psilocybin service facilitator,” which has unsettlingly fewer and less rigorous requirements than those mandated for psychotherapists. State-level governing agencies in Colorado are now gearing up to accept licensing applications in late 2024 for psilocybin “healing centers.” Even as our editorial team prepared this issue on non-ordinary states and psychedelics, the District of Columbia decriminalized psilocybin, and LSD garnered breakthrough status as a potential anxiety treatment.

Even more compelling than flashy headlines and breaking news is what’s been happening beyond the guardrails of clinical trials: at retreat centers, in quiet basements, and on Zoom integration calls. Quietly and unofficially, all manner of psychedelics are already being widely used as tools to heal intractable mental health conditions—and not just by a few renegade therapists. Prominent therapists all over the world are incorporating ketamine (which is currently legal to use), psilocybin, and MDMA into treatments with individuals and couples, sensitively navigating legal, ethical, and clinical gray areas to get clients the psychedelic-assisted therapeutic experiences they’re clamoring for.

“One interesting question arising from the increased fervor for psychedelics is ‘What’s the role of the therapist?’” says Ingmar Gorman, the CEO and lead trainer at the continuing education organization Fluence, which specializes in psychedelic-assisted therapy. “Some drug companies doing clinical trials see the healing that takes place as psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy—in other words, treatment where psychotherapy is central. But other companies are saying, ‘The role of the therapist is minimal; they’re only there to provide safety and make sure the participant isn’t in distress.’ These perspectives may directly impact treatment effectiveness, but they also matter when it comes to fees and insurance, policies, and treatment scalability. I believe these distinctions related to the therapist’s role are going to reshape our field over the next two to five years.”

In 2023, Lykos Therapeutics—previously known as the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies Public Benefit Corporation (MAPS PBC)—submitted an application to the Federal Drug Administration to review MDMA as a potential therapeutic medicine for the treatment of PTSD. In February of this year, the FDA granted their application priority review status. When I asked Gorman how this connects to legalization, he said, “There’s something called the Prescription Drug User Fee Act, or PDUFA. The PDUFA target action date is August 11, 2024. They’ll review Lykos’s application to determine whether MDMA could become a prescribable medicine. There’s no guarantee—the FDA might say ‘no,’ or ‘we need more data.’ But if they say ‘yes,’ then the DEA has 90 days to decide which schedule MDMA falls under. If you do the math, that means MDMA could be a legal medicine by November or December of this year.”

Gorman worries that if the FDA declares it needs more data, even the best researchers in the field might be hamstrung. Although longitudinal studies show lasting, long-term gains for people who’ve received psychedelic-assisted therapy—effectively treating conditions like PTSD—because study participants in clinical trials are quick to realize they’ve received an inactive dose in the control group or a psychedelic in the experimental group, it’s nearly impossible to do a truly blind controlled study of psychedelics, which weakens the validity of the research. That said, Gorman is cautiously optimistic about the path to legalization. After all, MDMA has made it this far.

Regardless of what happens on August 11, therapists today are facing a rapidly changing clinical landscape as a result of psychedelics. So what should the field be focused on now? What are the hopes? The concerns? Two prominent trauma researchers—world-famous psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk, bestselling author of The Body Keeps the Score, and psychologist Monnica Williams, a top thought leader in PTSD and one of the most influential women shaping the future of psychedelics—have answers that may surprise you.

Livia Kent: It seems that we’re well beyond needing to convince the therapy community of the therapeutic benefit of psychedelics. In your view, what should the conversation focus on now?

Bessel van der Kolk: Therapists know there’s a benefit, but they may not be aware of the specific benefits. I was part of a team that published three major research papers on the effectiveness of MDMA for healing trauma. One of them was chosen by the journal Science as one of the most important scientific breakthroughs of the year.

In my view, the most important finding of this research is that MDMA is particularly effective for treating people who suffer from developmental trauma disorder (DTD), those who’d been chronically abused and/or neglected by their caregivers from early childhood on. MDMA opens up the possibility of making changes to the entrenched characteristics that develop from being abused and neglected, and that get in the way of trauma healing.

Kent: How so?

Van der Kolk: Compared with the control group that received 36 hours of IFS-based therapy, those who had three days of therapy-assisted MDMA had significantly greater improvement in self-compassion, alexithymia, and various measures of self-regulation. Further analyses showed that changes in PTSD scores were due to these changes in mental capacities, which are common in DTD. That’s revolutionary because no other treatment has thus far been scientifically proven to be particularly helpful for DTD. People with this diagnosis make up the bulk of many clinical practices, and clinicians have tried a large variety of methods to treat them, with various degrees of success, but none has been as profound as what we found with MDMA.

On MDMA, you can go deeply into your past and see it from a new perspective. You can see that something happened to you at a certain point in your life and realize on a deep level that you did what you could, so chronic issues of shame and self-blame are highly mitigated. MDMA helps people significantly alter their relationship to themselves. They’re able to approach themselves with much more compassion. For example, chronic trauma often manifests in a brain fog where you don’t feel connected to yourself. The study showed MDMA was spectacularly useful in changing that.

One significant issue here is that our subjects were treated with extreme care. I can’t emphasize the importance of that proper care enough, because while you’re in the psychedelic state, your mind becomes wide open. You’re wide open to positive influences—to changing maladaptive ways of perceiving yourself—but you’re also vulnerable to negative influences. That’s why attention to set and setting is critical, and why therapists need to make sure they’re not being intrusive in any way. I hear about violations of this all the time, including by very experienced therapists.

People on psychedelics to heal trauma need to have somebody with them who’s completely there for them during the experience, someone with whom they have a deep feeling of trust—because that feeling becomes part of their internal experience. If they’re left by themselves or the therapist is preoccupied with other things and gets distracted, that lack of safety will be incorporated into the experience. That’s my grave concern for the future as we move into legalization: that therapists who haven’t been well trained to do this work will feel they can do it, and that clients will have negative experiences as a result.

Kent: In your view, what’s the best training for therapists interested in doing this work?

Van der Kolk: There are several organizations, like Fluence, that offer training. Institutions like the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) and the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS) also have solid programs. But in addition to getting the education and information, I think it’s critical to have the experience yourself—several times. You need to meet yourself on psychedelics and appreciate how vulnerable you become and how profoundly your mental processes change while taking them. If you haven’t had the experience, you can’t imagine what that’s like. In many ketamine-assisted therapy trainings people take turns being the subject and the sitter for each other.

In our MAPS study, we had two therapists with a subject for 36 hours. That’s worked very well, but it’s extraordinarily expensive, so it can’t be applied widely for ordinary conditions. We need to change the model so care can be delivered more economically—but without cutting corners on the deep attention to trust and safety that’s needed.

Kent: Do you have ideas about how we do that?

Van der Kolk: I think the ideal way to do it is in a retreat type of setting. Psychedelic experiences go very deep—you can’t help but use the word spiritual. This serious work can’t be done casually in between other stuff. This is not a quick in-and-out thing. Integration at the end is very important. You really need to take time off from your life to deeply immerse yourself in this therapy.

Again, the big challenge is still how to make this therapy accessible and safe to the largest number of people. Our reliance on insurance companies to make this possible is scary. We don’t want the capacity to heal determined by the insurance industry.

Kent: As we look toward the future of psychedelics and therapy, what are your hopes? What do you see happening?

Van der Kolk: I think this may just be the most important breakthrough in our field, maybe ever. And I’m aware of the dangers of people taking shortcuts and being sloppy with it.

My hope is that we’ll keep working to develop a much deeper understanding of the differential effects of ketamine, psilocybin, MDMA, and ayahuasca. We need to develop a much clearer understanding of how these substances are different for different people and who does best on which substance.

The other thing that needs to be investigated more fully is the finding that psychedelics seem to change core biological systems, including the systems that drive chronic pain and autoimmune issues. Trauma has a deep effect on the housekeeping of the body and on physical wellness. It’s a huge frontier, and I hope people will collect good data and look carefully at the full range of potential of these agents.

Livia Kent: What should the conversation about psychedelic-assisted therapy be focused on now?

Monnica Williams: We need to talk about accessibility, making sure that every group of people has access to these treatments. This has always been one of my biggest concerns with psychedelic therapy: is this going to be a treatment just for people with means?

Also, we need to make sure that everybody is at the table and included in the research. This is going to take widespread psychoeducation about psychedelics. In particular, communities that have suffered because of the war on drugs may be particularly wary of these treatments, and many religious communities may be averse to them. Part of the psychoeducation will be helping people understand that, for the most part, these aren’t addictive substances. They’re not going to change your personality or melt holes in your brain. But they are powerful, and there are risks to taking them.

For those reasons, I’m concerned that the recreational use of these substances will increase. Throughout history, around the world, in every society, the use of such substances has always included a wise, experienced guide, be that a traditional healer or a doctor. And that’s for good reason. We don’t yet have a cultural context for how we live with these substances once they’re legalized. What level of regulation should be in place, and why? I think we need to figure out and grapple with these things.

I’m also concerned that in our rush to promote access, we’ll cut corners, and people won’t get a safe or high-quality experience. That’s why I started a training program at the University of Ottawa for clinicians who want to incorporate these medicines into their practice. We’re launching a master’s degree in psychedelic and consciousness studies, which includes training on how to use these medicines in the appropriate clinical context.

I’m particularly excited because it’s an interdisciplinary program, and I believe we must understand these medicines in an interdisciplinary way because the use of them touches on so many different aspects of the human experience. It’s not just about medicine; it’s not just about therapy. There’s often a spiritual aspect to it, but it’s even beyond that. Psychedelics touch on so many different important realms that I worry we’ll take a reductionistic approach and think of them as just medicine or just chemicals.

Kent: Most of the research is focused on how psychedelic-assisted therapy can address trauma. Bessel van der Kolk’s research has shown it to be particularly effective for developmental trauma. Are there other areas you feel we should be looking at?

Williams: One of my main research interests is trauma due to experiences of racialization, marginalization, and oppression. This kind of trauma has similarities to developmental trauma because as a racialized person growing up in a racialized society, you’re constantly getting negative and false messages about who you are. That’s every bit as traumatizing as other kinds of developmental traumas. I have huge hopes that psychedelics can help people heal from these cultural traumas.

Kent: Do you have thoughts on how we provide this treatment to marginalized populations who might most need access to it?

Williams: Yes, I do—and my thoughts are anticapitalistic. Too many people are thinking, How can I cash in? But the fact of the matter is that these medicines shouldn’t be expensive. Psilocybin mushrooms grow naturally in just about every continent of the world. Whether it grows out of the ground or is made in a factory, finding ways to make sure the medicine is affordable is key to accessibility. This isn’t an area where we should be profiteering.

Kent: Anything else you’d like to make sure to tell our readers?

Williams: I’m a psychologist, and I’ll be the first to say I think psychologists are behind in terms of understanding their role in helping bring psychedelics safely to the public. We need to get past our aversion to risk and embrace our role in doing the research and assessments to create the treatments. I’m hoping this work will be included in all psychology training programs.

ILLUSTRATIONS © MR_MARCOM

Bessel van der Kolk

Bessel A. Van der Kolk, M.D., is a clinician, researcher and teacher in the area of post-traumatic stress. His work integrates developmental, neurobiological, psychodynamic and interpersonal aspects of the impact of trauma and its treatment. Dr. van der Kolk and his various collaborators have published extensively on the impact of trauma on development, such as dissociative problems, borderline personality and self-mutilation, cognitive development, memory, and the psychobiology of trauma. He has published over 150 peer reviewed scientific articles on such diverse topics as neuroimaging, self-injury, memory, neurofeedback, Developmental Trauma, yoga, theater and EMDR.

He is founder of the Trauma Center in Brookline, Massachusetts and president of the Trauma Research Foundation, which promotes clinical, scientific and educational projects. His 2014 #1 New York Times best seller, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Treatment of Trauma, transforms our understanding of traumatic stress, revealing how it literally rearranges the brain’s wiring – specifically areas dedicated to pleasure, engagement, control, and trust. He shows how these areas can be reactivated through innovative treatments including neurofeedback, somatically based therapies, EMDR, psychodrama, play, yoga, and other therapies.

Monnica Williams

Monnica T. Williams, PhD, is a board-certified licensed clinical psychologist who was named one of the top 25 thought leaders in PTSD by PTSD Journal. Her work has been featured in several major media outlets, including NPR, Huffington Post, CNN, and the New York Times. Dr. Williams has published over 100 book chapters and peer-reviewed articles focused on trauma and other anxiety-related disorders and cultural differences. She is an associate editor of the Behavior Therapist and New Ideas in Psychology, and serves on the editorial board of several scientific journals.

Livia Kent

Livia Kent, MFA, is the editor in chief of Psychotherapy Networker. She worked for 10 years with Rich Simon as managing editor of Psychotherapy Networker, and has collaborated with some of the most influential names in the mental health field on stories that have become widely read articles and bestselling books. She taught writing at American University as well as for various programs around the country. As a bibliotherapist, she’s facilitated therapy groups in Washington, DC-area schools and in the DC prison system. In 2020, she was named one of Folio Magazine’s Top Women in Media “Change-Makers.” She’s the recipient of Roux Magazine‘s Editor’s Choice Award, The Ledge Magazine‘s National Fiction Award, and American University’s Myra Sklarew Award for Original Novel.