3:21 a.m.

Awake.

One single solitary endlessly-repeating gnawing obliterating thought utterly consumes me:

Did that sonuvabitch respond to my email?

My body urges me to get up and find out.

“No,” my brain answers, “you can look in the morning.”

My brain is quite aware there’s no need for urgency. Soon the sun will be up and so will I. And within a minute or two after that, I will, as I do every day, as if I have no choice, position myself in front of the computer where—expectant, hopeful, yet filled with dread—I will religiously perform my morning devotion and discover what’s happened to the world since I last checked just before bedtime, as well as what the world has since delivered to my inbox, which this morning might even—fat chance!—include the sonuvabitch’s response.

“Look now!” my body insists.

“No.”

“Yes. Yes. Yes,” etc.

“Don’t do it,” my brain says to me (whoever “me” is).

“Go.”

“No.”

“Yes.”

“NO!”

My body shuts up. Middle-of-the-night torment has subsided. For a moment, in its place, middle-of-the-night peace.

Then, unexpectedly, before I even realize it, “I” seem to have decided something. My body has overcome my brain. “OK, dammit. YES! I’ll go look.”

Angrily, I throw off the covers. Determined, I sit at my desk. Manfully, I click the mouse. The computer, merely napping—never off—blinks awake and I’m confronted with a picture of stand-up comedy icon Lenny Bruce, leaning as if reeling from yet another shattering setback in a life littered with them. Today, I learn, is the 50th anniversary of Lenny’s morphine overdose. Fifty years! Marveling that an entire half-century has flown by—and that his famous Carnegie Hall concert was still another five years earlier than that—I find myself, before I even realize what I’m doing, clicking on some of his stand-up.

As I study the grainy videos and speculate on how high a rung Lenny stands on the Ladder of Funny Comedians (as opposed to the Ladder of Influential ones), my eye wanders. What’s that anomalous image over there on the right side of my screen? Another one of my heroes, the preternaturally articulate author Christopher Hitchens?! A very young Christopher Hitchens it is indeed, sporting, in retrospect, a very embarrassing haircut. With another flick of my finger—voilà!—now Christopher too is alive and kicking, “debating” the equally hyperverbal William F. Buckley and some idiot I’ve never seen before, with Hitchens apparently asserting the necessity for and positive influence of the women’s movement. Incredibly complex sentences are streaming from their mouths—Hitchens’s at machine-gun speed, Buckley’s drawn-out and nearly always incomprehensible—sentences and polysyllables that continue to astonish me for what must soon be at least 10 minutes: it’s nearing 4 o’clock! But with all those other Hitchens options looming over there on the right, who cares what time it is?

I’m transfixed. When the idiot guy cites Kierkegaard, well, I just have to laugh. Before I can understand why, I’m suddenly curious when it was exactly that Søren died. My manful right hand, aided by my nimble left, searches for Søren’s birth year which is—

“Wait a second,” my body, escaping from the hypnotic pull down this next rabbit hole of Wikipedia, reminds me, “what about that sonuvabitch’s email?!”

Sheepishly, fearfully, I click on my inbox with the same apprehension I used to feel when, at my first real job, I’d be summoned to my boss’s office where he’d savage my most-recently-submitted work product.

My inbox pops up. Twelve emails since I went to bed. Twelve! And not a one from the sonuvabitch. My left hand is massaging my right fist, which hurts, I realize, from pounding the desk.

As monumentally enraged as Sonny Corleone in The Godfather when he discovers his sister Connie has been beaten by her husband Carlo, my body commands me to see what rage-in-action really looks like—at least when rage is beautifully captured on film—by bringing up and studying, yet again, the sequence in which Sonny viciously exacts his revenge. My aching right hand obeys and clicks away. For what must be the 100th time, I admire the visual maelstrom, the choreographed chaos of the scene’s many moving parts—the kids, the cars, the spouting fire hydrant, the bystanders, and of course, the combatants—as Sonny catches up to Carlo on a crowded summer street and righteously repays domestic violence with kicks and punches and the lid of a garbage can. I’m smiling: Aristotle knew a thing or two about catharsis.

The chronological order of Henry VIII’s wives; that video of that porn star who reminds you of Ellen from 10th grade (Where’s Ellen now? you wonder, though not for long—she’s in Cupertino, at least according to Facebook); the view from the room in Florence you’re thinking of renting for a week; the Beyoncé-Coldplay Super Bowl duet; your prospective monthly Social Security benefit; the fluctuation of the Dow; the nearest Ethiopian restaurant; rain tomorrow night. The world at your fingertips. As enraged as the internet often makes me, I have to admit the overwhelming emotion it inspires in me is awe, a reaction reminiscent of the one television evoked in my father.

No matter how many times over the years he turned on the TV—always to him a newfangled invention that forever remained as astounding a piece of equipment as if it had been deposited in his home by extraterrestrials—each time he did, my father sat dumbstruck, entranced by its magical unfathomable powers: People! Live! In my living room! This thing from the science-fiction future had made its first appearance during his adulthood and never ceased being miraculous.

For me, on the other hand, TV was commonplace, nothing special, a given in the world I showed up in. Very much akin to my father’s reaction to TV, but in sharp contrast to my own, every single time I go online—no matter how many countless times I may have done it—I’m no less dumbfounded by all that the internet presents . . . and represents. Here I am, in my home, able to summon up, at my whim and pleasure, with a few mere clicks—a wizard with his wand—almost all the art and knowledge that mankind has ever produced, and communicate with damn near everyone on the planet. No need for a library. Or a plane. Or a phone.

Yet aside from churning out and replying to emails, what the hell do I mostly wind up using this wondrous device for? What do I wind up actually looking at? As my father, open-mouthed, took voyeuristic delight in watching people make asses of themselves on Allen Funt’s Candid Camera and smiled broadly, fascinated, as the sophisticated bons mots flew by on What’s My Line?, I spend my time mindlessly catching up on what Trump said to Jimmy Kimmel last night (or, irony of ironies, replaying what John Charles Daly said to Dorothy Kilgallen and her fellow What’s My Line? panelists as he invited her to begin the questioning of “tonight’s mystery guest” (the “tonight” in question usually having taken place well before Lenny’s fatal overdose). And just as my father was both enchanted by and ultimately chained to his screen, I suffer under the same illusion he did when it comes to mine: that it is I who’s selecting what I’m looking at. Click, read. Repeat. Click, view. Repeat. Click, send. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat, until I look up and ask myself, “Where’d the last 45 minutes go?”

Every day, every moment, we’re offered up a smorgasbord of choices and opportunities for information, entertainment, and communication. And every day, every moment, we must wade through the flood of incoming alerts and emails urgently demanding our time and attention, all the while knowing that peeking out, tempting us, lurking just beyond, is a plethora of stuff—an infinite ocean of stuff, in fact—that every hour of the day and night quietly waits for us to first stick our toe in so that it may then slowly begin to swallow us up . . . until we drown.

Look anywhere, everywhere. All these people—on the train, on the street, in the theater before the curtain rises and then again as soon as it falls—staring at their devices, in bondage, impatiently buzzing someone with an important message, and even more, hoping to be buzzed themselves. How much communication does a person need? What did we do before the digital revolution? Think? Worry? Daydream? Take in the sights? The buildings? The trees? Landscapes? Other people?

Did we smoke?

A lot of us smoked.

Today, anyone smoking is nothing more than a stupid anachronism; defiant perhaps, but massively stupid, nonetheless. Once upon a time, however, the cigarette was our social crutch, the shield we all carried to help us get through the horror of being alive. Regardless of the consequences to our health, it bestowed an aura of glamour and mystery. Gravitas. Danger. Addicted, sure, but smokers appeared to be contemplative, lost in thought. Serious. Romantic.

The Walkman and the iPod were a different kind of shield—they immersed us in music even as they cut us off from each other and the world. Then the iPhone ushered the world back in, reconnecting us, but the world it brought back wasn’t the one surrounding us, the one staring us right in the face, but rather, a virtual world apart, a world where life is elsewhere.

The internet connecting me to that world apart is so deeply ingrained in my consciousness it’s more than just a part of my nervous system: it seems to control it. Prone to addiction, I protect myself from my susceptibility to its siren’s call to be available and online 24/7 by refusing to upgrade my dumbphone to a smartphone, so that, at least when I’m away from home, I’m off the grid, the control ceases. (For similar reasons, I got rid of my TV decades ago—if I still had one I’d be watching Turner Classic Movies 24/7.)

Of course, this bucking of the cultural trend has its tradeoffs. Walking down the street, for example, I’ll never get to experience the exciting rush of being interrupted by someone’s terribly important email or Facebook post, nor will I ever be able to catch their latest Instagram or Snapchat offering. Nor, when sitting in a restaurant, am I ever sufficiently technologically armed to engage in the one-upmanship of instantly producing the answer to a critical question that may at any moment be stumping my tablemates—like the name of Carole Lombard’s first movie, for example. But by keeping myself bereft of a smartphone when I’m outside the house, I also escape the onslaught of invitations to read or do or watch or answer, but which, given its seductiveness and my susceptibility to its “charms,” are in essence, for me, commands to read or do or watch or answer. It’s true that wireless-less, I may be missing out on a really wonderful tweet, but at least for bits and pieces of time here and there, I’m free from the internet’s insatiable demands.

But then, at some point, inevitably, I’m back home, ceding control once again. The cycle resumes, the cycle of time wasted, time spent, as I’m once again hit with breaking wave after breaking wave of news that’s packaged to feel apocalyptic, with emails that by their very nature are made to feel urgent, by the battering rams of information and opinion. Fear, Urgency, Rabble-rousing, Catastrophe: The Four Horsemen of the internet. . . . And trivia . . . And aimless entertainment . . . And witty blogs . . . And celebrity gossip . . . And rockin’ webcasts . . . And hipster podcasts. The bottomless, relentless nature of it all has its deadening effect, each new breathlessly-reported event thrust into insignificance as it’s breathlessly shoved aside by new videos and text breathlessly reporting on the next game-`changing event. Eighty people killed by a truck? So yesterday. What about today? What about now? What’s happening now? Better yet, what’s happening tomorrow? Next week? In 2020?

But who am I to talk?

Hey, you, sonuvabitch, if you’re out there reading this, would you please take a minute and answer my goddamn email already? I gotta get some sleep.

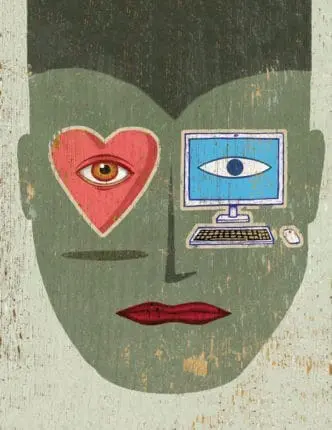

Illustration © Alberto Ruggieri/Illustrationsource.com

Fred Wistow

Fred Wistow is a former contributing editor to the Psychotherapy Networker and lives in New York City.