Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

Ever since Cain and Abel, sibling rivalry has been with us—big-time. Had the Bible been a tabloid, the headline would have screamed: “Brother kills brother! Murderer denies sibling responsibility and is cursed by God!” And if you think sisterhood is superior to brotherhood, just try the story of Rachel and Leah: “Older sister steals, then shares, younger sister’s intended hubby, Jacob!” As for the blended family of half-siblings that Jacob and his two wives produced and raised, you can read all about it in the saga of Joseph, whose half-brothers sell him into slavery, thereby setting in motion a story filled with so many lies, tricks, and turnabouts that even the most accomplished psychotherapist might have despaired of finding a way to the family reunion that eventually ensued.

These archetypal tales continue to possess us because our sibling bonds mark us—not as a curse like Cain’s, but as a roiling mix of love and anger, affection and rivalry, pride and guilt, loyalty and animosity, trust and suspicion. These emotions form the complex fabric of sibling (and family) life, and the imprinted patterns of these relationships stay with us, and affect us, in one way or another, throughout our lives.

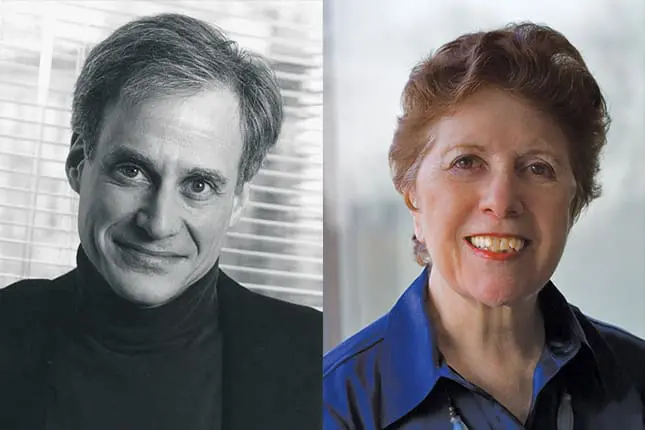

That is the theme of two new books, The Sibling Effect: What the Bonds among Brothers and Sisters Reveal About Us, by Jeffrey Kluger, and When a Brother or Sister Dies: Looking Back, Moving Forward, by Claire Berman. Though they overlap somewhat, the intended audience for each is distinct. Kluger’s book is directed at adult siblings who want to understand the dynamics, both positive and not, at play between their living siblings; it’s also directed at parents of siblings who want to raise kids who’ll continue to get along with each other, and even remain close, throughout their lives. By contrast, Berman focuses on the aftermath of a sibling’s death, and the grief that follows when the person you’ve probably known the longest over the course of your life is no longer present.

As a longtime writer and editor for Time, Jeffrey Kluger adeptly reports and synthesizes the results of numerous research studies conducted over the last few decades about all aspects of siblinghood—from the impact of birth order to the truth about who Mom really liked best; from the dynamics of sibling rivalry to the loving mutual care that siblings can provide; from the differences between sisters and brothers to the similarities—and individualities—of twins.

What differentiates Kluger’s book from other surveys of the subject is the insight he brings to bear from his own picaresque sibling journey: “I have full sibs, I have half sibs, and for a time I had step-sibs,” he writes. “My family went through divorces and remarriages and the later, blended home—and then watched that home explode, too. My brothers and I have fought the birth-order wars and struggled with ongoing rivalries for parental attention.”

The story itself is pretty messy. When Kluger’s parents divorced, the score-settling custody battle ended with another loss—the splitting up of the four brothers, with the oldest choosing to live with his embittered, distant father (who promptly sent him to boarding school, seldom seeing him) and the other three remaining with their dysfunctional mother, whose disastrous second marriage gave the Kluger boys two new stepsisters for the 15 months the union lasted. Their father’s second marriage was more successful, but for unexplained reasons, it wasn’t until his children from this union were already teenagers that they even learned of the existence of their four half-siblings. To top off the turmoil, from grade school on, the Kluger brothers had to learn to become a true band of brothers, taking care of each other, as their mother struggled with addiction.

It’s no wonder, then, that Kluger’s chapters on divorce, blended families, and the bonds that develop when older siblings end up raising younger siblings are suffused with a palpable mix of heartbreak and confusion, loss and anger. Kluger speaks from experience as he warns about the dangers of playing one sibling off against another—the family version of what politicians call triangulation—and alerts warring parents to remember that siblings learn how to resolve conflict—or not!—from their parents’ example. In sum, he writes, “Children are often the collateral casualties of even the most civilized separation.”

These chapters—fueled by personal narrative—shine and are worth the price of admission. Other chapters provide a solid surveylike introduction to the subject, chock-full of tips for parents struggling with the competing attentions of two or more kids. At the same time, however, more knowledgeable readers may wish Kluger had asked more probing questions of the experts he interviewed. A case in point is his discussion of the feelings of dethronement experienced by firstborns upon the birth of younger sibs, and the notion that every child is born into a different family configuration or “microenvironment,” each with its own dynamic. Professionals, who know this territory cold, might have appreciated more elaboration of the issues included, but new parents may find it to be a perspective-giving road map to the dynamics at play in their household.

Some chapters are less successful. Kluger’s chapter on the impact of birth order, for instance, breaks little new ground, instead rehashing relatively uncritically Frank Sulloway’s work and his bestselling book from several decades ago, Born to Rebel, which popularized the viewpoints that firstborns are more conscientious, conservative, and authoritarian, while children born later are more inclined to be rebellious risk-takers and innovators. Kluger includes the same material, despite the fact that quite a few researchers question Sulloway’s conclusions, or find them overly simplistic.

The fact that some of the sibling studies that Kruger refers to are either controversial (like Sulloway’s work) or limited in scope demonstrates how difficult it is to arrive at cut-and-dried, universal lessons about the sibling experience. The reason: there exists a seemingly infinite variety of family particularities that can influence the nature of any given sibling bond—starting with number of kids, how many boys versus how many girls, their difference in ages, the ages of the parents, the type of parenting styles, and the impact of ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds. As a result, many studies conclude with narrow findings, or with the warning that, depending on factors x, y, or z, sibling relationships can turn out one way, or perhaps another. For instance, it’s impossible for a parent not to have a favorite child, says Kluger, but whether being favored or not favored turns out to be a plus or a minus depends on the kid’s temperament, as well as on how the parents handle the situation.

This is another way of saying that studies can give us some general perspective on what to expect among siblings, but it’s variety and particularity that give each sibling story its richness and power, whether in the Bible, in Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, or in Kluger’s own moving tale.

Kluger mentions only in passing his concerns about his and his siblings’ health as they age and approach the inevitability of mortality, but he shies away from further mention of what it might mean for him to mourn one of his siblings. The omission, I think, is due to the fact that he himself couldn’t face thinking about it. After all, our siblings are part of our biographies from early on, and in our relationship to them, we find and define ourselves. When we grieve for a sibling, therefore, we can’t help but grieve for a lost part of our own history.

Yet the death of a brother or sister is often not acknowledged as the powerful loss it is, asserts Claire Berman in her instructive, poignant book, When a Brother or Sister Dies. Berman, author of eight other books about family relationships, was drawn to this subject in the wake of her sister’s death, in New York City, of heart disease, in September 2001, just days before the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center. The national outpouring of grief put into stark relief the relative insignificance of any individual loss; at the same time, it brought home the sense that in the public consciousness, the death of a sibling is often seen as a lesser loss, compared to that of a spouse, a parent, or a child. She quotes a woman who told her, “When my brother died, none of my friends came to the funeral. . . . They didn’t think it was important enough. One of them even said to me, ‘Why are you carrying on like this? It’s not as if you’ve lost a parent.” Not only does such insensitivity invalidate the real nature of grief, it fails to recognize that the death of one sibling can transform the lives of the surviving brother or sister, when, for instance, a surviving sibling becomes the one to shoulder the financial or emotional responsibility for raising the dead sibling’s children, or taking care of ailing parents.

Berman provides insight into the nature of grief that can be applied to any significant loss: there’s no single cookie-cutter approach to mourning, she reminds us; we each find our own way through grief. Relationships that were discordant in life can continue to raise, in memory, issues that can be tough to resolve. The key is to validate and acknowledge, rather than demean or disenfranchise, the importance of the sibling bond, both in life and in death.

Throughout, Berman presents in-depth case histories that dramatize many possible responses to grief, and the multifaceted ways that we continue to remember. Along the way, she quotes numerous sources (including The Psychotherapy Networker’s Marian Sandmaier, author of Original Kin: The Search for Connection among Adult Sisters and Brothers), and provides a comprehensive list of resources. Truly, her book shows, our siblings leave their mark upon us, as much in death as in life.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.