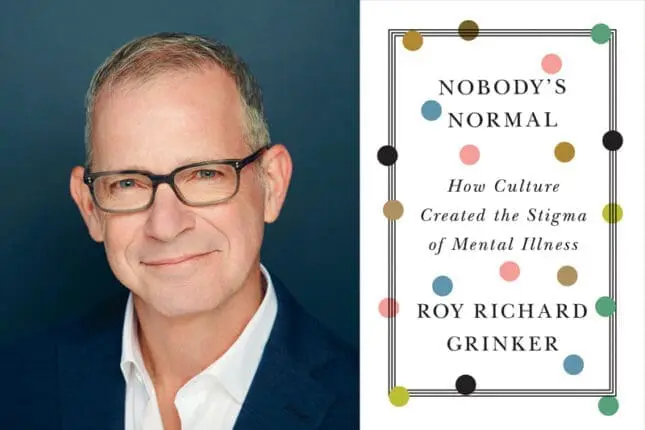

Nobody’s Normal: How Culture Created the Stigma of Mental Illness

by Roy Richard Grinker

W.W. Norton 381 pages

The very title of anthropologist Roy Richard Grinker’s new book, Nobody’s Normal: How Culture Created the Stigma of Mental Illness, made me eager to read it. It brought back in full force the indelible childhood memory of my mother’s choked explanation of why we so seldom saw her beloved younger sister, my Aunt Anne. She was not well, my mother told me in a pained, hushed voice. She suffered from a type of illness that affected the way her mind worked, and as a result, she had to stay at a special kind of hospital. And, she added in even fainter tones, because not everyone understood this type of illness, it was best not to share this secret with anyone else.

I nodded solemnly, mirroring my mother’s tone of equal parts compassion and worry, but I was left both troubled and mystified by this mixed message of love, clouded by some vague fear of—what?

Now, with the help of Grinker’s thoughtful volume, I’m able to reframe this conversation as my personal introduction to the way the stigma of mental illness gets inside our heads. It’s a process, deftly explained by Grinker, by which a given culture’s underlying beliefs, assumptions, and moral judgments teach us how to perceive and respond to mental illness. From this perspective, mine was a textbook case of how, starting in childhood, we absorb and internalize our milieu’s criteria for labeling and stigmatizing those who aren’t “like us.”

Grinker credits the influential social psychologist and sociologist Erving Goffman for formulating and publicizing the concept of stigma: society’s shunning or ostracizing of a person or group based solely on appearance, behavior, beliefs, customs, or ways of thinking or living in the world that don’t align with that of the majority and are judged unacceptable or undesirable. In the case of mental illness, it’s through stigma, Grinker writes, that society makes psychiatric conditions “a double illness: first, the ailment itself, and second, society’s negative judgment.”

That point hit home for me. My memory came from the 1950s, an era when Aunt Anne’s condition would have been—and was, I learned from eavesdropping on my father—seen as a blot against the pristine “normalcy” to which post–World War II America aspired. That time stamp is relevant because, as Grinker points out, such attitudes can—and do—change over time. Witness the readiness of so many public figures today to break the silence about their own or their family members’ struggles with different facets of mental illness.

Grinker further emphasizes that stigma around mental illness isn’t a part of many cultures across the globe—a point he proves with extensive research on perceptions of mental illness in communities ranging from South Korea to Namibia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. For instance, Tamzo, who lives in a remote village in the Kalahari Desert, walks 24 miles to the main village each month to pick up medicine that will keep at bay the distressing, hallucinatory voices he hears. He has schizophrenia, but because his community “accepts differences we [Americans] have shunned,” they accept and take care of him, Grinker writes. “No one there expects a condition like schizophrenia or autism to define a person as a whole.”

Contrast that example to America, where ongoing advances toward greater inclusion and acceptance of not just mental illness but many types of neurological differences, including autism, still have a ways to go. With that in mind, Grinker documents, first, how those attitudes became entrenched to begin with and, second, how contemporary culture is paving the way toward change.

Grinker begins by chronicling the evolution of Western attitudes toward the mentally ill. It was in the late Middle Ages that “social undesirables” started to be rounded up and incarcerated in asylums, such as the infamous British institution that came to be known as Bedlam, he writes. A major reason they were considered undesirable was that they were unable to work, or be economically productive—a disability frowned upon in Western economies increasingly driven by market values that judged people’s worth primarily by their ability to make money and support themselves. At first, it didn’t even matter why someone couldn’t work: “People who worked deserved to be free; people who did not work, even people maimed in an accident, deserved only to be excluded,” Grinker writes.

Over time, such undifferentiated ostracization gave way to the building of separate institutions: prisons to house lawbreakers, and hospitals to treat the mentally ill. How ironic, then, that despite reform movements from the Industrial Revolution and on through today, the failures of our national mental health system have led to the destruction of most mental health hospitals, whose closures have cast many thousands of mentally ill people onto the streets, where they’re often picked up by the police for disturbing the peace and left to languish, for the most part untreated, in jail.

Grinker also brings his own family’s involvement with psychiatry and mental illness into the story. His great-grandfather, Julius, a nationally recognized early 20th-century neurologist, staunchly believed “that insanity was caused by a person’s inability to control their impulses—especially the desire to shop.” The misogynistic stigma was implicit, with this type of nervous mania, known at the time as hysteria, the diagnosis of choice for women.

This feminized stigma only changed in the wake of World War I, Grinker recounts, with the advent of a new mental health phenomenon: the syndrome that was then called shell shock. A devastatingly large number of soldiers, mostly male, were exhibiting many of the symptoms of hysteria, including anxiety, panic, lethargy, and physical fits affecting mind and body. Their suffering generated public sympathy for mental distress incurred as a result of their war service, but military physicians worried that labeling brave men with the diagnosis of a “female” disorder would lead them to refuse treatment. Hence, shell shock. Grinker comments on this little-known legacy of war as destigmatizing to mental illness and neurodiversity: “Though the compassion quickly receded during peacetime, the nations at war had trained doctors to do things they could never have imagined before, such as providing short-term therapies . . . or developing surgical methods to repair the genitals of men wounded in combat—the same methods that would make possible the first gender-affirming surgeries.”

During World War II, Julius’s son Roy, Grinker’s grandfather and a psychiatrist, further contributed to destigmatizing mental illness, having studied with and been psychoanalyzed by Freud in Vienna in the 1930s. Stationed in Algeria in the midst of Rommel’s desert assault on the Allied forces, he sought to apply a humanistic understanding to soldiers’ psychic wounds, bringing relief by listening sympathetically as they recounted their experiences of combat. It was a kind of short-term psychoanalysis to help staunch the terrible symptoms that, in the aftermath of the wars since then, we began to call posttraumatic stress disorder. Indeed, Grinker writes, his grandfather’s work and the resulting study that he coauthored with a colleague, Men Under Stress, “played an important role in transforming psychiatry from asylum administration to short-term therapy for a more diverse and less acutely ill patient population.”

But the perception of what’s normal, and the stigmatization of what’s not, persists. Grinker, whose daughter Isabel has a form of autism, brings particular insight to the ways in which companies are beginning to change their perceptions of the skills that employees on the spectrum can contribute. James Mahoney, director of the Autism at Work Program at JPMorgan Chase, explained to Grinker that “capable people on the autism spectrum often get shut down because of the interview process; traditional interviews amplify the deficits of autism but not what the autistic person is actually good at,” their conversational awkwardness getting in the way of presenting their expertise, say, at computer coding. The company addressed that obstacle via an email-based job application, which focused on skills and experience, and began providing coaching support and mentors to help their new employees overcome any social challenges. This is one among many successful employment programs, illustrative of a positive trend in acceptance and destigmatization.

Grinker’s argument is powerful, the breadth of his knowledge extraordinary; however, because he jumps back and forth so frequently among so many perspectives—from psychiatry to anthropology to economics to history to memoir—the experience he weaves can be dizzying. Nor will everyone agree with Grinker’s view of capitalism as a major factor driving the stigma of mental illness.

But his point is essential. “Stigma is not a thing but a process, and we can change its course,” he writes. And the key to doing so is accepting that nobody’s normal.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.