Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

No One Cares about Crazy People: The Chaos and Heartbreak of Mental Health in America

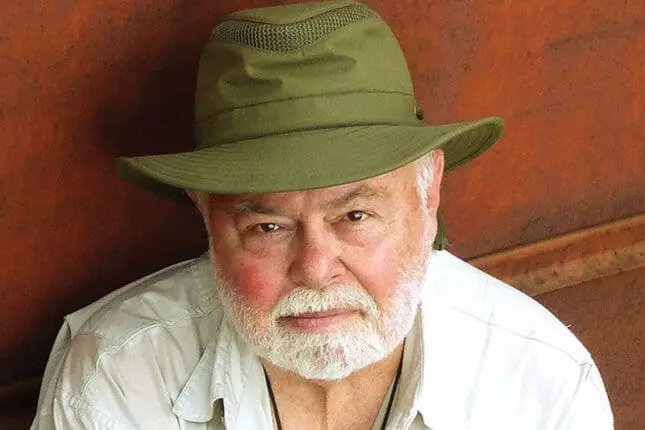

by Ron Powers

Hachette Books

360 pages

9780316341172

I hope you do not ‘enjoy’ this book. I hope you are wounded by it,” writes Pulitzer Prize–winning author Ron Powers at the start of his searing account of living with and through his sons’ devastating struggles with schizophrenia. His own emotional scars are fully visible as he describes the heartbreak and horror of watching his adored, spirited sons, while still in their late adolescence and young adulthood, begin suddenly and inexplicably to fall prey to increasingly irrational and erratic thoughts and behaviors, ultimately leading to the diagnosis of schizophrenia in both children. He also burns with high-octane rage—and outrage—as he surveys the sad history of mental healthcare in our country, a trajectory that’s led to the woefully underfunded and inadequate patchwork system of today.

Powers deftly intertwines his personal family story with the social and political history of how we treat the mentally ill, resulting in a grim indictment of the public’s moral and political failure to care. Along the way, he provides advice for families and mental health professionals alike, gleaned from his own experience, about the multitude of challenges that come with the diagnosis of schizophrenia or any serious mental illness. Typically, the long-haul journey begins with a mystified family dealing with an initial psychotic break, followed by the hard work of persuading the patient he or she needs help, from there pinning down an effective treatment and medication dosage, and then getting the patient to maintain the treatment regimen and stay on track. Accompanying all that is the task of navigating complex healthcare regulations and insurance provisions—that is, if the patient is fortunate enough to have sufficient coverage. Each step is agonizing, and Powers gives voice to the isolation, frustration, and sense of helplessness that patients and their loved ones often feel.

He’s taken his main title, No One Cares about Crazy People, from an email written in 2010 by an administrative aide to Scott Walker, then in the running for governor of Wisconsin. To tamp down worries over scandalous mismanagement of a local mental health complex (which she dubbed “our looney bin”), the aide assured her colleagues on Walker’s staff that “no one cares about crazy people.” And statistics bear this out, all too brutally. Between 2009 and 2011, Powers writes, “states cumulatively cut more than $1.8 billion from their budgets for services for children and adults living with mental illness. California led the nationwide slashing with cuts totaling $587.4 million.”

Lack of care is a recurring theme in his overview of the evolution—and more often devolution—of treatment of the mentally ill. Tracing this history is important, Powers asserts, because it tells us how we got to the sorry state in which we find ourselves now. Thus, with a tone of bitter irony, he guides us through a horror show, starting with the founding of London’s notorious Bedlam asylum in 1247. Infamous for its “beating, shackling, taunting, starving, hygienic neglect,” and other cruelties toward its “lunatick” inmates, it served for centuries as a model for other facilities in Europe and America, where the mentally ill were locked away and neglected, their inexplicable behaviors and appalling treatment alike remaining out of sight and out of mind to the rest of society.

It wasn’t until the 19th century that social reformers like Dorothea Dix began to succeed in their push for a more enlightened “moral treatment” in asylums, which began to be built in calming, bucolic settings and staffed by humane attendants, rather than jailers. Already by the beginning of the 20th century, however, such institutions had become overcrowded, understaffed, and underfunded. New abuses had become common, ranging from forced sterilization to lobotomies to warehouse-like conditions to the overuse and misuse of a new class of antipsychotic drugs that were falsely hyped as wonder cures when their actual purpose was to sedate patients so they’d be easier to manage.

Powers is right to fume at Big Pharma for its egregious marketing practices and overpromising of early schizophrenia medications. At the same time, I wish he’d provided more information about some of the subsequent advances that have improved many patients’ lives, including that of his son Dean. Even so, it was against the backdrop of Big Pharma’s false promises for “curing” schizophrenia that the antipsychiatry movement gained added traction, with outspoken critics like Thomas Szasz, Michel Foucault, and R. D. Laing loudly declaring that mental illness was a myth. The stage was set for the massive deinstitutionalization movement that started emptying state mental hospitals in the 1960s.

But where would the patients go instead? The political promise was to replace the mammoth state mental hospitals with smaller, community-based hospitals and local health services. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen. From 1955 to today, the availability of inpatient psychiatric beds has shrunk by 95 percent. According to a study by ethicists at the University of Pennsylvania medical school, “US jails and prisons have become the nation’s largest mental health care facilities,” with half of all inmates suffering from a mental illness or substance abuse disorder.

Powers believes that reform will come only if more people are made to care, and that’s why he conjoins this public history to his private one. That too few people care, he says, is due to seeing the psychiatrically ill as “others,” whose peculiar, bizarre, or violent behaviors elicit fear and loathing, rather than compassion. These fears are compounded by the mystifying symptoms that can accompany schizophrenia, such as delusions, hallucinations, and the hearing of voices.

For Powers and his wife, Honoree, the onset of their sons’ schizophrenia dramatized just how unforeseeable and mystifying this transformation can be for a family. As Powers writes, “Something terrible happened to my sons, and I want to know what and why.” Thus, lovingly but sometimes with too many specifics, he combs through the mostly sunny saga of their entire family history. It’s clear that he and his wife are haunted by the fear that they missed a clue, perhaps an incident that seemed minor or escaped their notice at the time, that might have been a harbinger of what was to come. It’s an understandable impulse, but one doomed to heartbreak and futility. As Powers points out, despite the existence of tens of thousands of research studies seeking to tease out schizophrenia’s underlying causes, we still possess little definitive knowledge about the combination of any number of genetic and environmental factors that could set the disease in motion.

Just how complex the genetics are can be seen from the conclusions of a 2014 report by the Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. “After examining the genomes of some 37,000 people with schizophrenia and comparing them with those of more than 113,000 healthy subjects,” Powers writes, “the group claimed to have identified an astounding 128 gene variants connected with schizophrenia. These genes occupied 108 locations on the genome, with most of them having never before been associated with the affliction.” In other words, even though there’s no question that genes play a part, their exact role still remains unclear.

However, schizophrenia, which afflicts about one percent of the general population, does tend to run in families, with about 10 percent of immediate family members of someone with the disease having it, too. There’s a higher than normal risk if aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents have had the disease. Powers recounts a striking story of Honoree recalling her father, an alcoholic, pulling out each and every one of his teeth with pliers. Although he presents this incident without comment, one wonders if his wife’s father suffered from some form of psychiatric illness.

Powers is also interested in exploring the potential correlation between schizophrenia and the presence of high-level cognitive and creative abilities—the age-old conceit of the mad artist-genius-scientist. This idea draws his particular attention because Kevin, his younger son, showed outsized musical talent, starting in toddlerhood; Dean, the older, also developed into a highly capable musician. Many studies have attempted to corroborate such a link, but the results have been mixed.

Additionally, Powers looks at the role that stress may play in amplifying the severity of a given case of schizophrenia. Researchers cite family dysfunction and the intensity of urban life as two major sources of such stress. But while Dean and Kevin were still young, the highly functioning, loving Powers family moved from New York city’s hurried atmosphere to the calm of a campus town in Vermont. Not until Dean was a junior in high school did the family confront a major crisis, when he crashed the car he was driving, seriously injuring his date. Although eventually pardoned, Dean was sentenced to several months of house arrest for negligence, and he and the family were subjected to a campaign of harassment initiated by the injured girl’s parents. Uncomfortable in a community that had once embraced them, the Powers family soon moved to another town, and both boys switched high schools.

It’s tempting to speculate, but impossible to prove, whether this stressful period—which on the surface, everyone seemed to weather as well as possible under the circumstances—affected the course of either Dean’s or Kevin’s subsequent descent into schizophrenia. And it wasn’t until four years later that Kevin, then age 17, began to exhibit alarming symptoms of hallucination, self-aggrandizement, and disorientation.

Powers ponders all these possibilities, but the only conclusion he arrives at is that “the most useful weapon in the meager arsenal [for treating schizophrenia] is early intervention. Early and persistent. No cures exist for mental illness, but the quicker and more accurately the early symptoms are noticed and treated, the better the prospects for minimizing the effects.” One of his main goals in writing this book, Powers continues, is “to arm other families with a sense of urgency that perhaps came to us too late: When symptoms occur in a loved one, assume the worst until a professional convinces you otherwise. Act quickly, and keep acting. If necessary, act to the limit of your means. Tough advice. Tough world.” This is a cry from the heart, voicing the despair of families dealing with mental illness and wondering “if only”—the unstoppable refrain of the sum of uncertainties of schizophrenia. Still, from a practical point of view, I wasn’t sure how much more quickly Powers (or anyone other than a trained clinician) could’ve picked up or acted on the elusiveness of Kevin’s initial symptoms, which seemed to him just occasional and random strands of conversation.

But how do you help someone who’s neither willing nor ready to accept such help? Alas, it was Kevin’s anosognosia—a condition common to schizophrenia that impairs people’s self-awareness of their illness and leads them to deny it—that prevented him from taking the medications that may have helped him. Although I wish Powers had told readers about the different medications and therapies that were offered to or refused by Kevin, he doesn’t go into those details, nor does he speculate on whether a different regimen would’ve proved more effective. Sadly, three years into his illness, Kevin hanged himself in his parents’ basement.

And there was more tragedy ahead. In the midst of Kevin’s downward spiral, Dean had begun his own descent, ultimately attempting, and fortunately surviving, his own suicide attempt. The harrowing litany of each son’s psychotic episodes, hospital stays, and struggles against despair reads like the bleakest of nightmares, relieved only by the fact that at age 35, Dean remains stable, is successfully maintaining his medication regimen, and is ready to move into a house of his own in a Vermont town near his parents.

That’s as close to a semi-happy ending as Powers can provide, along with the overall message writ large throughout—some people do care about crazy people.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.