Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future

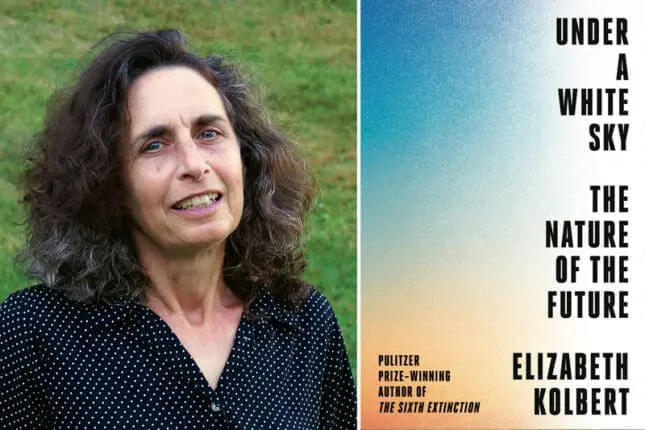

by Elizabeth Kolbert

Crown 228 pages

978-0593136270

Another day, another environmental emergency. Take your pick from the continually expanding list: surging levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, seemingly unending wildfires, record-breaking temperatures, warming oceans, melting ice, rising sea levels, dwindling species, and on and on.

Headlines like these once shocked us; now they’ve become so familiar that many psychotherapists have noticed a trend among clients that they’re calling ecological despair. It might be tempting to dismiss environmental anxieties as abstract worries, but for most people, urban and rural, the underlying threats of climate change are hitting closer to home—and possibly home itself—as the situation worsens. This is the environmental trauma of our time.

In The Green Boat: Reviving Ourselves in Our Capsized Culture, a book on the psychological impact of climate change, psychotherapist Mary Pipher acknowledged that, while peering into the reality of climate change is nothing less than daunting, we must confront it, both for ourselves and for the sake of future generations. She proposes social activism as a double-barreled response: at once a route that can lead from despair to hope and a means toward achieving practical, positive change, whether through voicing protest against environmentally damaging projects, supporting green legislation, or helping elect eco-friendly political candidates.

And to act responsibly, we need to be familiar with what science teaches us about the human impact on the environment. That brings me to journalist Elizabeth Kolbert, who proves in her latest book, Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future, why she’s among today’s best, most trustworthy, and preeminent writers on the effects of climate change.

Here, as in her previous books—including The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, which won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize in general nonfiction, and Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change—Kolbert presents our planetary dilemma without flinching.

As most people know, we now live in the newest geological epoch, the Anthropocene, defined by the overwhelming impact of human behavior on all aspects of the world. She states, “We have dammed or diverted most of the world’s major rivers. Our fertilizer plants and legume crops fix more nitrogen than all terrestrial ecosystems combined, and our planes, cars, and power stations emit about a hundred times more carbon dioxide than volcanoes do… In the age of man, there is nowhere to go, and this includes the deepest trenches of the oceans and the middle of the Antarctic ice sheet, that does not already bear our Friday-like footprints.” Only a handful of times in its entire history has the earth undergone such wide-ranging and dramatic changes as humans have brought about, she asserts, the most recent being “the asteroid impact that ended the reign of the dinosaurs, sixty-six million years ago.”

Whew! So where does that leave us? Being the optimist that I am, I catch glimmers of hope from the climate and clean energy initiatives introduced by President Joseph Biden, as well as from the burgeoning youth environmentalist movement spearheaded by Greta Thunberg. But the realist in me also asks, Will that be enough to bring us back from the brink?

Kolbert explores another question that’s so ironic we might be tempted to laugh if the situation weren’t so desperate. Do our best chances lie in finding ways to interfere with nature once again—this time, in hopes of fixing the out-of-control environmental damage we put in motion in the first place?

In search of answers, Kolbert visits endangered locales around the world to interview the scientists, biologists, and geoengineers at work on these kinds of interventions. She begins on the garbage-strewn Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, built at the turn of the 20th century to reverse the direction of the Chicago River so sewage wouldn’t flow into and contaminate the city’s drinking water. By the early 2000s, invasive species, such as giant-sized Asian carp and zebra mussels, had infiltrated this artificial channel, and because it contained portals to the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes, many native species were now in danger of extinction.

The solution? Large electric barriers between the channel and other water sources to zap the intruders. As for the tons of dead fish that result, they’re mostly ground into fertilizer. And at least one culinary entrepreneur is experimenting with turning them into frozen fish cakes. In fact, Kolbert notes that the sample she tried was rather tasty.

Elsewhere, at the southern end of the Mississippi River, Kolbert surveys the “land-loss crisis” along the Louisiana coast. There, she notes, the state “sheds another football field’s worth of land” every 90 minutes, and “the very reason the region is disintegrating, coming apart like an old shoe” is the thousands of miles of levees, flood walls, and other structures built by the Army Corps of Engineers over many decades to prevent the rising river from spilling onto dry land. By shackling the river into a set, immovable course, the massive project thwarted the natural process that had helped build up the land for millennia, via the sediment that rolling waters would carry with it and deposit along the way. Among the proposed solutions: two new engineering projects that aim to divert the flow of the sediment once again, but this time to nearby basins, where mud and sand can build and sustain marshes and wetlands.

She also reports on a variety of ventures to reverse carbon dioxide emissions—or preferably, remove them from the atmosphere altogether. One of the most extreme possibilities would be to simulate a giant volcanic explosion by shooting large amounts of a substance such as calcium carbonate into the stratosphere, to serve, like volcanic ash, to block out the sun and reduce global temperatures.

Can attempts such as these to combat environmental disasters caused by humans with more human intervention succeed? Should we risk the more unknown, unintended consequences of continued experiments with nature? And most immediately, will reading and knowing about these projects actually help ameliorate our own ecological despair? Or will this be cause for even more existential angst?

My advice is to listen to the scientists she interviews. They also struggle with doubt, worry, anxiety. And nonetheless, they continue their work, their search for possibilities.

As I read, I kept thinking that they’re no more immune to despair than we are. Many of the scientists openly admit the burden of responsibility and level of anxiety they live with, and it’s clear that their worries about the potential negative impacts of their projects, whether they fail or even succeed, are real and justifiable. But they persevere in their work nonetheless.

As I reached the end of Under a White Sky, I wondered if these scientists have any other choice but to dedicate their highly trained skills, knowledge, and ingenuity to the attempt to mend, or at least slow down, the environmental damage already present. And what choice do we have but to act as we can, taking individual daily measurements to curb our carbon footprint, urging or engaging in environmental activism, helping those in despair find the resilience to join in that effort? That persistence is the best hope we have.

PHOTO © JOHN KLEINER

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.