Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

Several years ago, I received feedback after presenting an anxiety workshop along the lines of “Lynn’s use of humor indicates that she does not take anxiety seriously.” I’m always open to observations from workshop participants, but I disagreed with this one. Humor often allows us to enter those sticky places we might otherwise avoid. It entertains us while we’re learning. Laughing connects us and pushes back at anxiety’s demand that we take life too seriously.

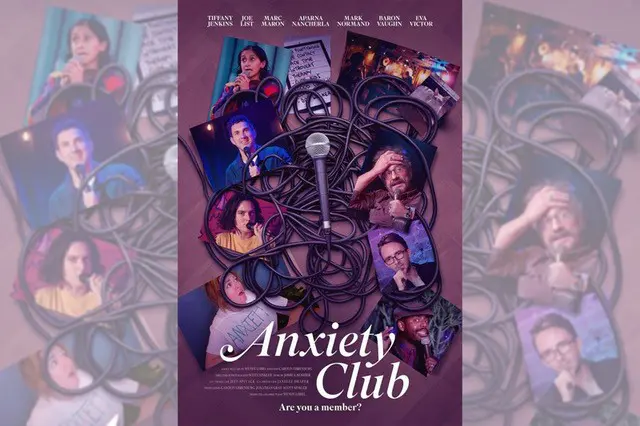

So I had high hopes for the 2025 documentary The Anxiety Club, directed and produced by Wendy Lobel and billed as a heartfelt and humorous exploration of anxiety through the lives of several anxious stand-up comedians. Humor and anxiety! This was my jam! Not only do I admire the courage and cleverness of stand-up comedians, I’m also a sucker for learning about anything that goes on behind the scenes. How does an anxious person choose a profession that requires experimenting, failure, vulnerability and harsh judgment as the point of entry? Will I discover anything new about the familiar trope that comedians use humor to mask their pain? I was ready to be entertained and perhaps enlightened. My critical self also wanted to see how anxiety would be portrayed. What might the average watcher learn about it? And what would they take away about therapy in general?

From the opening scene and throughout the documentary, I was struck by how fervently several of the comedians claimed anxiety as their full identity. It was who they were and, based on the shared clips of their stand up, the source of virtually all their material. Joe List, a sweet self-deprecating guy, says, “I have every kind of anxiety you can have…my whole life is fear and anxiety based.” Mark Normand, a successful comedian who’s been featured on Conan, The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon, and The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, describes his social anxiety and internal dialogue as dictating his every waking moment. When we meet his girlfriend, he says, “She’s incredibly anxious also, which is nice.”

Well-known comedian and podcaster Marc Maron says that with anxiety “everything becomes a hassle.” Although he sees maturity and life experience as helpful to managing his anxiety, he also comments on how incapable he is of experiencing joy. I began to wonder: are their lives completely focused on feeling anxious and then performing sets about how overwhelmingly anxious they are? The clips were funny, for sure, but I was craving some funny content that stepped away from this unidimensional life experience. Can you be funny, I wanted to ask them, about anything else? (That would be the assignment I’d give them if they were my clients: write a comedy set not focused on your anxiety. What else is interesting about you and your world?)

Much of the documentary focuses on Tiffany Jenkins, a comedian and author who creates You Tube content with millions of followers. Tiffany has two children and her anxiety about their safety is front and center. The average viewer will find Tiffany’s story compelling. Her catastrophic parenting is off the charts, with constant—and I mean constant—warnings and restrictions. “There’s so much kidnapping and trafficking going on in the world,” she says. She talks to her kids (who look to be about seven and nine) “way too much” about kidnapping. She requires they be on the same floor in their house. She hovers while they eat, warning about choking. She tucks a taser in her sports bra when she takes them to the playground.

Tiffany begins therapy with Natalie Noel, a specialist in anxiety disorders and OCD. To her credit, Noel does not shy away from doing exposure therapy. “Of course she’ll do exposure therapy for anxiety and OCD,” you might be thinking. But current research indicates that despite its effectiveness, many therapists avoid exposure therapy due to their own hesitancy to feel or cause any distress.

Overall, Noel is direct but supportive. She’s clear in her explanations, takes an active stance, and gives Tiffany homework. However, I blanched at her approach with Tiffany’s intrusive thoughts. Tiffany’s most disturbing thoughts revolve around harm or death coming to her children. “We’re going to do a lot of ‘maybe, maybe not,’” says Noel. She then has Tiffany write repeatedly, several times a day, “Maybe my kids will die today.”

Nope. As someone who’s specialized in anxiety for three decades and written three books on the subject, I don’t go anywhere near the content of the thoughts, particularly disturbing intrusive ones. No considering the possibility. No “maybe this could happen.” Imagine a young adult man with the intrusive thought that maybe he’s a pedophile based on agreeing with his mom that his six-year-old niece is “cute.” (True story.) I’d never say to this young man, “Well, maybe you are a pedophile, maybe you’re not!” And I would absolutely never have him write repeatedly “maybe today I’ll discover I’m a pedophile” five times a day. Noel then creates what she calls a “worry script,” a very graphic story she writes about Tiffany witnessing her daughter choking to death in front of her on the kitchen floor. Tiffany is to read this story repeatedly to “burn out whatever fear you have.”

The goal, of course, is to make intrusive thoughts less powerful so they don’t dictate behavior, and Noel states as much. But I prefer to convey the message that bizarre and disturbing intrusive thoughts are a result solely of one’s disorder and nothing more. Clearly identifying them as such is essential. Engaging with them is not. In fact, engaging with them or analyzing them at all can be devastating. People who believe their intrusive thoughts “might” be true often become despondent, full of shame and more fear. I’ve seen the result of this harmful therapeutic approach.

Luckily, Tiffany does learn to recognize her catastrophic thought patterns and create distance from them, while allowing her kids more autonomy. And I like that Noel repeatedly emphasizes that they’re putting Tiffany’s children first, and that her anxiety impacts them directly—and not in a good way. “You don’t love your children more because you’re anxious,” Noel says. It’s a powerful moment. Noel has Tiffany do several exposure experiments that support the skill of taking action despite the anxious storytelling that keeps her in a loop of inaction, and Tiffany makes progress. But my guess is that anyone watching the “worry script” approach portrayed in this documentary might stay far away from getting help with their OCD.

When the other comedians share what they’ve learned in therapy, their takeaways are good, solid stuff about stepping out of the anxiety narrative. Maron, for example, knows that “most of what you’re reacting to is something your brain is making up.” Several of them also acknowledge the harmful impact their anxiety has on their connection with loved ones and with others in general. But I was still disheartened by how much their work, play, and love lives seemed to remain contaminated by the pervasiveness of their anxious inner worlds. One comedian described his anxiety as a “false friend,” but it’s an omnipresent friend, nonetheless.

On a more positive note, the comedians demonstrate the anxiety-busting skills they use as professional entertainers and writers. Most talk about the need to persist in creating material (despite how they feel), the willingness to tolerate judgement and uncertainty on stage, and the external focus on the audience that takes them out of their own internal dialogues. There’s repetition, consistency, and the building of confidence as they produce good work. These anxious comedians are in fact doing the opposite of what their disorder demands. It’s impressive! Anxiety is part of them, but it’s not all of them. I wish they—and this documentary—had made this point crystal clear. I wanted to hear it acknowledged. As the film ended, I hoped these comedians would come to recognize the ways they were reworking their all-consuming “anxious” identity just as they reworked, revised and delivered a great joke.

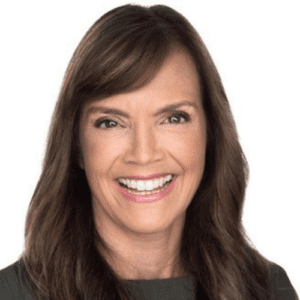

Lynn Lyons

Lynn Lyons, LICSW, is a speaker, trainer, and practicing clinician specializing in the treatment of anxious families. She’s the coauthor of Anxious Kids, Anxious Parents and is the cohost of the podcast Flusterclux. Her latest book for adults is The Anxiety Audit.