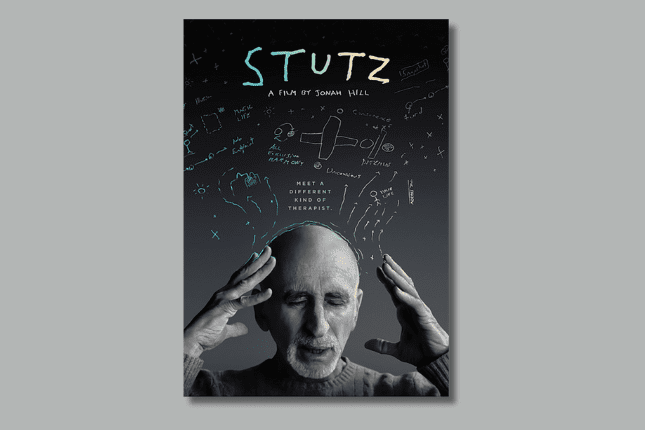

Stutz

Directed by Jonah Hill, Strong Baby Productions

On a rainy Saturday night in early spring, seated on a couch with my husband and a bowl of microwaved popcorn, I debated our movie-night options for a few minutes before settling on Stutz, a documentary about an actor and his therapist.

“The guy from Moneyball!” I exclaimed as Jonah Hill appeared onscreen.

“Peter Brand,” my husband confirmed, referring to Hill’s Moneyball character.

Hill, I quickly realized, was also the guy who’d played Seth, my 13-year-old son’s favorite misfit in the blockbuster movie Superbad.

As a therapist, I try to avoid immersing myself in any form of entertainment related to therapy on weekends, but watching an actor who’d won over my husband and son embark on a journey of self-exploration seemed like a worthwhile Saturday night activity. I settled more deeply into the couch.

Over the course of Stutz, my husband and I were introduced to an array of tools and concepts therapist Phil Stutz—a bald, soft-spoken, 75-year-old Los Angeles-based doctor—offers Hill. These included the Maze (a metaphor representing the way we get trapped in the past), Life Force (an energy we can cultivate by improving our relationship to our bodies, other people, and ourselves), Grateful Flow (a state of mind we can consciously generate if we want to break free of negative thinking), and String of Pearls (a technique for engaging in small, life-affirming acts—like getting out of bed in the morning—when we feel hopeless).

Stutz’s tools immediately struck me as creative re-envisionings of strategies and concepts most therapists are already familiar with. What made them useful wasn’t the rarity or newness of what they conveyed: it was how Stutz crystalized big ideas into bite-sized interventions that people could easily self-administer.

I was so taken with the documentary that I asked to review it for this magazine. Then, a few months later, as my completed review was moving through the editorial process that precedes publication, a friend forwarded me a link with the message, “Did you see this?” The link took me to a news story about Sarah Brady, Jonah Hill’s ex-girlfriend, who the day before had made public a series of text exchanges she claimed were between her and Hill. In one of them, Hill—or someone with the name Jonah in her contact list—tells Brady he doesn’t support her surfing with men, posting pictures of herself in a bikini on social media, modeling for a living, or having friendships with women he deems unstable. But the clincher was, the Jonah person on the text thread calls the imposition of his preferences onto Brady’s choices and behaviors “setting boundaries.”

Twenty-four hours later, social media channels were blowing up with heated debates about coercive control and the ways therapy-speak gets weaponized in relationships.

Shit, I thought selfishly, that ruins my review. But then I thought about it harder.

What did these allegations bring to light—if anything—about the benefits and perils of therapy? Can you be a vulnerable, likable guy with your therapist and still abuse the power afforded you by fame, money, or the privileges that accompany your gender? Did this new development invalidate the insights and pleasure I’d experienced watching Hill’s film? Whichever side you came down on around the type of alleged “boundary setting” in question—whether you think Hill was merely expressing his preferences or you think Brady was being coercively controlled—did it undermine Stutz’s message: that all human beings suffer, mess up, and can get better with loving support and access to the right therapeutic tools?

In my view, what made this project so different from Hill’s other films was that, despite being an actor, he wasn’t playing a character in it. He was being—or trying to be—himself: an anxious, nearly middle-aged guy in a therapist’s office with a desire to help others and amplify his therapist’s message. The documentary was clearly about a lot of things—therapy, loss, pain, healing, and relationships—but at its core, it reflected Hill’s desire to be vulnerable and genuine. Half-way through the film, for example, Hill admits that because production had dragged on for years, he’d been putting on the same clothes day after day to create an illusion of continuity. He lets us in on the fact that he’s not actually shooting scenes in Stutz’ real office—they’re on a makeshift set with a digitally simulated background projected onto a green screen. He also removes the wig he’s been wearing to try to approximate the way he looked eight months prior, revealing that—at this point in time—he’s got a shaved head.

In Stutz, Hill succeeds at something you don’t see many filmmakers succeeding at these days, given how hopelessly spoiled we are as entertainment consumers by billion-dollar thrillers full of flaming helicopters and elaborate car chases to hold our increasingly fragmented attention. He weaves together a gripping, tender, 90-minute story out of intimate questions and answers—something I haven’t seen done since My Dinner with Andre. Although it’s not the first time someone has made a movie about a client and their therapist—the most memorable being The Gloria Films, where Carl Rogers, Fritz Perls, and Albert Ellis showcase three different therapeutic approaches with the same client—I’m pretty sure this is the first time we’re privy to a client’s internal struggles as both a director and someone on the receiving end of a therapist’s interventions.

Unlike mainstream movies about therapy intended only to entertain, like Analyze This and What About Bob? Hill’s stated purpose in making Stutz is unusual, at least as far as Hollywood motivations go. In the opening scene, he declares that he wants to give a wider audience a taste of a set of therapy tools he values, ones that have helped him improve his own mental health. But with the recent trouble that’s emerged between Hill and his ex, you may be tempted to ask, “Did therapy really help him, or did it just give him more ways of trying to control romantic partners?” I’m not sure we have to know the answer to this question, or even buy into Hill’s charitable intentions, to appreciate what Stutz offers us. Hill never pretends he’s healed of all the ways his traumas play out in his life. Instead, he readily admits to struggling with his therapist’s teachings, many of which center around making peace with one’s own and others’ imperfections.

“If you could do it perfectly,” his therapist Stutz says when Hill expresses self-doubt about his own creative process, “it would contradict everything we’re doing here.”

One of the things I enjoyed most about this film was its raw language and risqué humor, even when it crossed a line—such as when Stutz jokes about having had sex with Hill’s mother (it’s clear from Stutz’ delivery and Hill’s response that this comment isn’t meant to be taken seriously), or when he calls Hill an asshole (given the Brady texts, some viewers may wonder whether Stutz’s lighthearted insult was unintentionally diagnostic). As uncomfortable as it sometimes is, I admire the edgy humor that flows so easily between them.

I’ve always wanted to ride invisible waves of comic momentum in conversation, but in my family, cracking jokes could get you smacked, so I learned to avoid being funny. Avoiding jokes and expletives has also become an unquestioned, rock-solid part of my professional identity. On the rare occasions when I’ve joked or cursed in session, it’s been on the heels of a client’s sarcastic or ironic remark, or while mirroring their frustration. And yet here, in Hill’s documentary, was Stutz making all kinds of edgy, provocative comments—including telling the entire psychiatric establishment to go fuck itself.

“Don’t go on a fucking comedy routine right now, bro,” Hill tells Stutz at one point, calling him out for trying to be funny while talking about his fear of women.

“I can’t tell you how many jokes I’ve had to repress in the last three minutes,” Stutz murmurs sheepishly in response.

“I have the same disease,” Hill commiserates. “Avoid emotion by making jokes.”

Stutz and Hill have a lot more in common than just the joking-to-avoid-emotion disease, though. We learn they’ve both been profoundly impacted by the unexpected deaths of their brothers. They both have a hard time getting out of bed in the morning, though for different reasons—Stutz because he has Parkinson’s, and Hill, presumably, because he struggles with anxiety, depressive symptoms, or a combination of both. In traditional therapy, you’d never know so much about your therapist’s medical history and childhood traumas, but because these two men agreed to collaborate creatively outside of sessions, we get to see their dynamic spilling—gushing sometimes—over the protective guardrails that most mental health professionals rely on to keep the therapist–client relationship in its proper lane.

“I feel like making this movie is complicated for a lot of reasons,” Hill admits toward the film’s end. “You’re my therapist and if I was having trouble with something, you’d be who I’d talk to about it.” With Stutz listening attentively, Hill continues, “I keep asking myself, ‘Was this a fucking terrible idea for a patient to make a movie about his therapist?’” The power differential tips back and forth periodically between Hill and Stutz, exposing their insecurities, weaknesses, and strengths.

Now, the text exchanges between Hill and Brady have me wondering anew about power—particularly about the role of power and language in the form of therapy-speak. There’s a lot of talk these days about the need to communicate clearly, but what constitutes communication that reveals vulnerabilities and expresses truth and communication that manipulates and shames? And who gets to decide which is which?

When I first watched Stutz, the thing that inspired me to want to write this review was the visceral experience of Hill and Stutz’s tender, complicated, client–therapist relationship. By the time the closing credits appeared, both of them had openly expressed their love and their fear of losing each other. Their bond stoked my appetite for more of what they somehow managed to capture against all odds: their unique brand of sweet, off-kilter therapeutic lightning in a bottle. It left me eager to explore new ways of bringing my own flavor of the “uniquely personal” into my connection with clients.

I’m not suggesting all therapists should curse like sailors, lapse into comedy routines, openly share details of personal losses and traumas in session or agree to be the focus of grateful clients’ creative projects. What I am suggesting is that Stutz has a lot to offer viewers even—or maybe especially—in the wake of the Hill–Brady text-exchange debacle. After all, the film is still what it was originally intended to be—an engrossing documentary showcasing a powerful set of therapy tools. But it’s become something else, too—part of a larger and much-needed cultural conversation about the often-hidden dynamics of coercive control and the ways that even the shiniest therapy concepts can help or hurt, reveal or obscure, depending on how they’re wielded.

Alicia Muñoz

Alicia Muñoz, LPC, is a certified couples therapist, and author of several books, including Stop Overthinking Your Relationship, No More Fighting, and A Year of Us. Over the past 18 years, she’s provided individual, group, and couples therapy in clinical settings, including Bellevue Hospital in New York, NY. Muñoz currently works as a senior writer and editor at Psychotherapy Networker. You can learn more about her at www.aliciamunoz.com.