When working with couples, it’s easy to get drawn into narratives that begin the second a partner reacts to a trigger. And yet, as a relationship therapist with 40 years of experience, I’ve found that many sources of tension and disconnection are often outside of clients’ awareness, held in implicit memories—also called body memories—that are made up of old, unchallenged messages about how the world works. There can be so much anguish in the room when partners spiral into vicious cycles of blame and defensiveness that it’s tempting to focus on easing the immediate emotional pain by whatever means necessary, but this can be a diversion from the larger therapeutic task of healing old wounds that exert control below the surface.

Having trained in body-based models for trauma treatment—most extensively in Somatic Experiencing—I’ve begun noticing opportunities for creatively applying certain somatic strategies used in individual therapy to my work with couples. I find this moves them beyond the content of arguments into the deeper roots of what disconnects them. I’ve seen over and over that when one or both partners are distressed, they’re able to access only so much cognitively. We hold emotional information—which includes beliefs about our strengths and weaknesses, how others view us, and who we should and shouldn’t trust—in our bodies. As Peter Levine says, this important information lives beneath words. But how do you bring somatic knowing into couples work, which is fraught with reactivity and defensive patterns?

Rabbit Holes

Married for 25 years, Kyle and Melissa sought couples therapy with me because they hadn’t had sex in a year and were generally feeling less close. According to Kyle, a stocky, bright-eyed man in his early 50s, Melissa had become increasingly critical of him over the last few years. He felt disheartened and perplexed.

“I honestly don’t know what she wants from me,” he blurted out in one of our first sessions. “She asks for more romance; I bring her flowers. Then she rolls her eyes and says, ‘You couldn’t think of anything more original than flowers?’ I can’t win.”

Melissa, a willowy brunette with piercing blue eyes, had been quick to defend herself. “You know I don’t like flowers. I’ve never liked flowers. When I say I want more romance, I mean I want more of what feels romantic to me.”

They reported having a good partnership in many ways. They’d successfully launched their three children, although Melissa described their daughter, Charlie, as “high maintenance.” It frustrated and annoyed Melissa that her youngest daughter seemed reluctant to take on many of the basic responsibilities of adulthood. Kyle exhibited more patience, which Melissa called enabling.

One session about two months into our work together, before they’d fully settled into their respective chairs, Kyle and Melissa began recounting an argument they’d had over the weekend.

“We were walking along the river, and Kyle’s phone rang,” Melissa said, her arms crossed over her chest. “It was our time together, but he answered the phone anyway.”

“You completely overreacted,” Kyle chimed in. “You kept shouting at me, ‘Why did you answer your phone? Why?’ You’d think I’d murdered someone.”

“Don’t exaggerate,” Melissa snapped.

“It was our daughter.” Kyle looked at me, shaking his head. “All I did was answer her phone call. I’d been helping her put together her first résumé, and she had another question.”

“She’s not five years old,” Melissa said, waving her hand dismissively. “She’s a 22-year-old woman. We’d spoken to her in the car for 20 minutes already. You don’t have to pick up the phone every time she calls!”

As with many couples, when we talked about their fight, Kyle and Melissa focused on the hurtful comments they’d hurled at each other after Charlie’s call. They also focused on who was right, and who had the worst reaction.

“You said I was self-centered and implied I’m a bad mother,” Melissa said.

“You said I love Charlie more than you,” Kyle said, “which is outrageous.”

I know from personal and clinical experience that once an escalation like this is under way, most people lose any ability to explore what triggered the original argument. When partners feel threatened—either because they believe they’re being attacked or because their own feelings are uncomfortable or overwhelming—they go into survival mode. They might fight, walk out, or shut down. Their ability to remain vulnerable or think rationally is compromised. The true source of the disconnection remains deeply buried under the reaction to the reaction to the reaction.

“Let’s slow this down,” I said. “Take a few breaths, exhaling through your mouth as if you’re holding a straw between your lips.” I know that when people become agitated or anxious, their nervous system can get dysregulated, as if the gas pedal is stuck on go. This kind of breathing brings the nervous system into balance by stimulating the relaxation response.

As they tried this, still glaring at each other, several thoughts began competing with one another in my head. I’m not sure the kind of romance Melissa longs for is realistic after 30 years of marriage. Should I bring that into the discussion? I wondered. No, that might send her out the door. Should I revisit the concept of re-romanticizing their sexual relationship? I thought. What is Melissa really longing for?

Rather than going down any of these rabbit holes, I decided to return to the path I trusted, which meant backing up and helping Kyle and Melissa focus—in a new way that got beneath the words—on the first few seconds of the interaction that had started their fight in the first place. I hoped this would help us uncover the original trigger, so we could get to the real root of their conflict. I call this clinical maneuver The First 30-Seconds Technique.

Scratching the Surface

“Let’s start at the beginning,” I said. “I’m going to invite you both to return to the moment when you’re walking by the river, before you hear Kyle’s cell phone ring. Feel free to close your eyes. See what you saw then, hear what you heard—the sound of the river gurgling, birds, insects, whatever.”

Facing each other with their knees nearly touching, Melissa closed her eyes and visibly relaxed. Kyle kept his eyes open, but I noticed his jaw unclench.

“I just want to have time alone with my husband,” Melissa said, her lower lip and chin trembling slightly. “Is that too much to ask? Just a little time together. No interruptions.”

“I have an idea,” Kyle announced, exhaling audibly as a crease appeared between his eyebrows. “I won’t bring my phone in the future. I’ll leave it in the car. Problem solved.”

Melissa shrugged and opened her eyes.

“Would that be a step toward uninterrupted time together?” I asked tentatively. Although this wasn’t exactly where I’d hoped they’d take my invitation, I appreciated that Kyle wanted to solve the problem and avoid future ruptures by agreeing on guidelines.

“Sure, I guess,” Melissa said. “It would help.”

“You sound hesitant,” I reflected. “Is there something else you want?”

“When the phone rings, and we’re together, I want Kyle to ask, ‘Hey, should I pick this up, or let it go to voicemail?’ I want to be a priority even when someone calls.”

“Could you do that, Kyle?” I asked.

He nodded.

We’d made some progress. Kyle was showing goodwill, and Melissa was articulating her needs. I could’ve easily accepted this resolution as complete. Afterall, aren’t devices of all kinds interfering in everyone’s relationships these days? Agreeing on how to prevent them from interrupting a couple’s alone time seemed like a step in the right direction. But something was still gnawing at me. Melissa’s jaw remained clenched, and Kyle kept glancing out the window. He looked deflated.

There seemed to be more going on here that we hadn’t yet explored. When this happens in a couple’s session, my heart rate speeds up a bit and my curiosity gets piqued. I find myself wondering what adverse early life experiences held in implicit memory might have had an impact on my clients, contributing to current misunderstandings, misperceptions, and overreactions.

As I looked at Kyle and Melissa, I read their body language. The body speaks in sensations, gestures, facial expressions, posture, and changes in tone of voice, skin color, and breathing. Any shift in a person’s body language provides me with an opportunity to bring up emotional information that isn’t in either partner’s awareness at that moment.

“I’m so glad we’ve got some guidelines for your walks moving forward,” I said. “But can we stay in that moment by the river a little longer? It might help us understand more about what’s happening on a deeper level.”

Melissa nodded and looked at me expectantly. Although Kyle shrugged, he seemed willing to suspend judgement about where I might be heading with this.

The First 30 Seconds

“See if you can recall what you felt as the phone started ringing when Charlie called,” I encouraged Melissa.

“I felt mad,” she said.

“Were there any other feelings alongside the anger?” I asked, knowing that anger often masks more vulnerable and uncomfortable emotions.

“No,” she answered quickly.

Is Melissa so upset because it was Charlie who called? I wondered. Should I bring up her relationship with her daughter, which we know to be somewhat fraught? But rather than changing our focus based on these musings, I turned my attention back to their body language. If there was one thing I was sure of in that moment, it was that Kyle and Melissa’s bodies held the information we were looking for.

Kyle was slumped in his chair. He looked more collapsed than comfortable. His face looked pinched. He was a business analyst, and anything that wasn’t logical unsettled him. He was also a kind man, who clearly cared deeply about Melissa. He’d shared in previous sessions that he grew up with a stern, critical father, who was hard to please. His entire childhood, he’d tried to stay under his dad’s radar and avoid showing any emotion that might invite ire or disappointment. It dawned on me that I was probably seeing a version of young Kyle sitting here, facing his father in the form of Melissa, who criticized him and gave him no real indication of how he could make her happy.

“Imagine there’s a bridge between your world and Melissa’s world,” I said to him, “meaning that you each have unique perspectives, experiences, and feelings. Can you cross over that bridge, step into Melissa’s world, and mirror what she says as we try to go a bit deeper?”

Kyle sat up in his chair. I was giving him something concrete and achievable to do. “I can try,” he said.

I know from years of doing this work that if a partner can be fully present, listening and reflecting back what they hear without editing, agreeing, or disagreeing, there’s a good chance their partner can drop down into deeper layers of their body and mind. Mirroring in this context is much more than repeating words back. It’s saying the words in the same cadence and tone to reflect the intention of what’s being communicated. To mirror in this way, Kyle needed to suspend his preconceptions and cue his curiosity. He needed to open himself to learning more about what it felt like to be in Melissa’s shoes.

“Are you noticing any sensations in your body, Melissa?” I asked.

“My throat feels tight, and there’s a heaviness in my chest,” she responded.

“If that heaviness had its own voice, what would it say?”

After a pause, she said, “I felt unimportant when you answered your phone.”

Kyle’s face softened. “What I’m hearing,” he mirrored, “is that you felt unimportant when I answered the phone. Is that it?”

Tears welled up in Melissa’s eyes. She met Kyle’s gaze, nodded, and then looked down again.

“Can you put what you’re feeling into words?” I asked.

Looking at Kyle, she responded, “I’m terrified for you to know that I felt unimportant. I don’t want you to know how important it is to me to feel important to you. I guess I don’t want you to have that kind of power over me.”

“As you say that out loud, what sensations do you notice in your body?” I asked.

“My throat still feels tight, and there’s a knot in my stomach.”

“When you tune into that knot, are there any images or memories that pop up?”

Without missing a beat, Melissa said, “I remember shutting myself in the bathroom when I was a kid—crying. I was scared my mother would hear me.”

With Kyle continuing to mirror, Melissa went on to describe her mother’s volatile behavior. One minute she’d be nice and the next, angry. Melissa felt she was only noticed by her mother when she irritated her.

“I felt like I needed to be on guard constantly,” she admitted.

“Is there a decision you made about that as a child?” I asked.

“Yeah,” she responded, “I resolved not to show any vulnerability around my mother, to hide any sign that I was affected by her erratic moods. Otherwise, I risked becoming a target.”

Kyle continued to gaze at Melissa, only now, his eyes were glistening.

“Wow,” Melissa said, reaching out and touching Kyle’s hand. “I had no idea that I’ve been acting with you the way I acted with my mom. I’ve been trying to be invulnerable.”

Implicit Memory

These events in Melissa’s childhood were known to her, but she hadn’t connected the dots between them and the dynamic in her relationship with her husband. This isn’t uncommon for partners who fight with one another but haven’t yet gained conscious access to implicit memories that shape their interactions.

One way to understand how implicit memory makes itself known is to imagine that a child is hit by a red truck when they’re five years old. They completely recover from their physical injuries, and at age 35, they’re standing at an intersection. A red truck passes, and they flinch with no conscious awareness of the significance of a red truck in their personal history. Although they may clearly remember the accident that took place long ago, its memory isn’t in their consciousness at that moment.

The emotional impact of adverse experiences early in life can be held in implicit memory for years, even a lifetime. But with what was being held in Melissa’s implicit memory now explicit, it was possible for the process known as memory reconsolidation to occur. Memory reconsolidation is a natural phenomenon in the brain that updates the nervous system when the right conditions are present. When an emotional learning from the past is triggered in the present, it can be replaced or modified with new information from the reality of the current moment.

“Would you be willing to look into each other’s eyes?” I asked.

Kyle was already leaning toward Melissa, holding her hands. He exuded empathy and care.

“Melissa, as you look into Kyle’s eyes, do you feel you can trust him?

“Yes,” she said.

“Do you feel you can be vulnerable with him?” I continued.

“Yes, I do,” she said. “I know I can.”

As I watched this deeper connection unfold between them, a chill traveled up my spine. They’d arrived exactly where they needed to be. In recognizing that she could feel safe being vulnerable with Kyle in a way she couldn’t with her mother, a new learning was replacing one of Melissa’s old childhood learnings.

It now made so much sense to me—and also, it seemed, to them—why Melissa yearned to be special, to experience romance with Kyle, to be doted on and given attention. It was a result, in part, of her mother not being attuned to her. Having lived in an atmosphere of trepidation and unfulfilled longing as a child, Melissa wanted attention and special treatment while at the same time being unwilling to risk letting her guard down. She didn’t want to be targeted and hurt again. It also made sense that Kyle had felt frustrated in his attempts to please her, as there really hadn’t been an open door for him to move through. He’d felt inadequate, just as he had as a child, which had led him to withdraw from Melissa even more.

In previous sessions, we’d focused on Melissa’s frustration that Kyle wasn’t being romantic enough. I’d put on my behavioral-sex-therapist hat, and we’d discussed how they could re-romanticize their relationship. But because we hadn’t identified what was preventing Melissa from being vulnerable, we’d made little progress. No one can melt into a sexual embrace from behind a protective shield. Another misstep I’d made had involved allowing their conflicting feelings about their daughter to become a focus of our work. Though it was true that Melissa both envied and felt uncomfortable with Kyle’s attentiveness to Charlie, it wasn’t the root cause of their disconnect. Without backing up to those first 30 seconds and tracking Melissa’s body sensations, I suspect this session’s takeaway might have been limited to an agreement about when to use their phones.

Case Commentary

By Jordan Dann

Deborah Fox’s case study demonstrates that effective couples therapy requires the therapist to alternate the focus of the session between the felt experience of each individual and the observable phenomena of the couple’s dynamic while holding in one’s awareness each individual’s respective family history. That’s a lot—even for seasoned therapists! Fortunately for Kyle and Melissa, Fox’s coregulated, relational, attentive curiosity creates enough safety and support for them to confront their uncomfortable feelings and make important discoveries about the unconscious forces driving their painful dynamic.

In my work, I’ve often noticed clients’ impatience to get out of their uncomfortable feelings. They long to escape the emotional messiness of their relationship, demanding, “Give me tools!” or begging, “Don’t you have an exercise that will fix this?” I appreciate how Fox normalizes the compelling impulse we so often feel as therapists to rescue or resolve clients’ problems. And I could relate to her inner dialogue as she works through the choice points she faces with Kyle and Melissa and keeps herself from getting inducted into their relational field in a way that would take the work off track or pull the focus to only one side of the dyadic system.

That’s why I thought Fox’s “the first 30 seconds technique” was particularly deft. By helping them attune to the bodily sensations around the trigger of Kyle’s receiving a phone call from their daughter during a walk, it allowed them to get beneath their words and explore their implicit memories. I often tell my supervisees, “Early developmental parts are waiting and listening for enough somatic and relational safety so that they can speak and be heard.” Fox guided Kyle to do this by asking him to “walk across the bridge” and engage in empathic attunement with his wife’s childhood experience. This is the gift couples can bring to one another when the land mines of the past explode in the present. They can learn to collaborate empathetically and coregulate one another’s nervous systems in a way that brings them back to the present, building their capacity to stay connected in what David Schnarch calls the crucible of conflict. By slowing down and deepening, rather than problem-solving, Fox helped Melissa feel safe enough to get a bird’s-eye view of how her history shows up in the present while helping Kyle let down his guard and feel into his wife’s emotional experience. This increased Melissa’s capacity for mentalization.

Developing a couple’s metacognition and mentalization skills is one of the most powerful ways therapists can support couples. Over time, as these relational capacities become stronger, each individual can develop a cohesive narrative, integrating disowned or denied aspects of themselves—the way Melissa began to. In time, integration increases a couple’s awareness and sense of freedom. They learn that they don’t have to react in the same predictable ways; they have options. I tell the couples I work with, “It’s good if you know your attachment history, and it’s best when you know one another’s. That way, when one of you forgets, the other can remember for you.” Over time, alongside the old story of danger and disconnection, a new story of safety and connection begins.

ILLUSTRATION BY SALLY WERN COMPORT

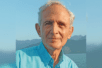

Deborah J. Fox

Deborah J. Fox, MSW, is a Washington, DC-based AASECT-certified sex therapist and a certified Imago relationship therapist in private practice. She conducts workshops and consultation groups on couples therapy, sex therapy, and the treatment of sexual trauma. Contact: debfox.com or deborahfoxdc@gmail.com

Jordan Dann

Jordan Dann, LP, is a nationally certified and NYS-licensed psychoanalyst in private practice in New York City with advanced training as a Gestalt therapist, Somatic Experiencing Practitioner, and Imago Relationship Therapist. She’s also an author and speaker, and has spent many years coaching and directing actors. She serves as an Associate Faculty member at the Gestalt Associates for Psychotherapy and runs supervision and workshops for emerging clinicians with PMA Mental Health Counseling. Instagram: @jordandann.