Weaving together Buddhist philosophy and storytelling, clinical psychologist and spiritual teacher Jack Kornfield explored the nature of therapeutic transformation by evoking the core elements of psychological healing—being witnessed and loved.

There was a young army lieutenant who got angry so often, and caused so much conflict, that his superior officer ordered him to do an eight-week mindfulness training course. One day, during the sixth week of the training, he stopped by the grocery store. It was crowded, the checkout lines were long, and he was tired. To make matters worse, the woman in front of him had only one item and should’ve been in the express line. His irritation only grew when she got to the front of the line and the clerk started cooing over the baby she was holding. When she actually handed the baby to the clerk, he went ballistic inside: We’re all trying to get home! What are they doing?!

He could feel the anger rise, but because he’d begun to train in mindfulness, he could also feel the pain that came with it: the stress and tension that came with holding it. So as he’d learned to do, he took some breaths, acknowledged what the anger feels like, and let it subside. By the time it was his turn, he was calmer, so he said to the clerk, “That was a cute kid you were holding.” And she said, “Oh, he’s my boy. You see, my husband was in the military. He was killed in combat last year, so now I have to work full time. My mom brings my boy in once a day so I can see him.” Hearing this brought him to tears.

Besides illustrating how quick we can be to judge others, and equally quick to judge ourselves for that matter, this story shows that it’s possible to train the heart and the mind, to move through this world in a different way than our reactive, fearful, and confused patterns tell us to. Of course, as you know with your clients, this shift might be slow, but a change in perspective is possible. And I want to honor you, so many of you therapists, for holding the fear, the confusion, the pain, and the possibility of this time in the world. You are the midwives, the shamans, the heart-holders of our culture. No amount of technology is going to stop the continuing violence, warfare, racism, environmental destruction, tribalism in the world. So it’s essential that we meet these outer aspects of humanity by growing the inner heart of our humanity, and our profession can help with this transformation of consciousness.

The poet Rilke said, “Ultimately, it’s upon our vulnerability that we depend.” We depend on others when we’re infants. We depend on others to stop at the red light so we can go through the green. In so many ways, we’re interwoven with one another, and we’re vulnerable. The question is, how do we hold our vulnerability? How do we navigate the ocean of tears and the unbearable beauty that make up life? How do we hold praise and blame, gain and loss, birth and death, joy and sorrow?

As therapists, we have tools to help people with all these aspects. And yet, as we all know, underneath it all, what’s critical to any kind of healing is to be witnessed and loved. Maybe that’s the essence of it all: to love another human being. And in that love to see something beautiful in the other and to encourage that to flower more than anything else. That witnessing and appreciation is so desperately needed by people, especially those who are suffering.

In Buddhist psychology, the essential vision is of an innate dignity that’s in every single human being. As Nelson Mandela says, “It never hurts to see the good in someone. They often act the better because of it.” And Thomas Merton talked about seeing the secret beauty of each person. He said, “If you could really see that beauty, you’d get down on your knees and worship everybody who walked by, and all that they’ve gone through.” In India, it’s called the glance of mercy—when a teacher, or guru, looks at you with so much love, that it just melts all your doubts, and you’re seen as worthy.

An Ohio math teacher once had an unruly class. So one day, she paused her lesson and had all 31 students write everyone’s name on a piece of paper. She said, “Take the rest of the time and write something that you admire or like in each one of these people.” She collected the responses, cut them up, pasted them together, and some months later, she passed them back out. What the students ended up with was their name and 31 things people admired about them.

Two or three years later, she got a call from the mom of Billy, who’d been in that class. “Billy went into the military and was killed in the Middle East,” the mom said. “Would you come to his memorial?” The teacher went, and as they were standing at Billy’s graveside, the mother turned to her and said, “Billy carried very few things on the battlefield, but this was in his pocket.” And she unfolded the piece of paper with the 31 things that people had admired about him. And Billy’s classmate on the other side of her said, “Oh, I always carry mine too,” and she pulled it out of her purse. And a young man said, “Oh, I made it part of my wedding ceremony.”

There’s something so remarkable about seeing the beauty in another human being. It brings about more possibility for change than almost anything else that we can do. And out of this quality of presence comes healing. And we offer our presence to help people be tolerant of their own humanity. James Baldwin writes, “I imagine one of the reasons people cling to their hate and ignorance so stubbornly is because they sense that once hate is gone, they’d be forced to deal with their own pain.” And when we can’t bear our human predicament, we project it onto others. So to learn to tend ourselves is not just an inward act: it’s a political act.

As Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh said, “When the crowded Vietnamese refugee boats met with storms or pirates, if everyone panicked, all would be lost. But if even one person remained centered and calm, it was enough. It showed the way for everyone to survive.” So as therapists, you’re not just in the role of tending to individual spirits; you’re carrying something that the culture needs to survive and flower.

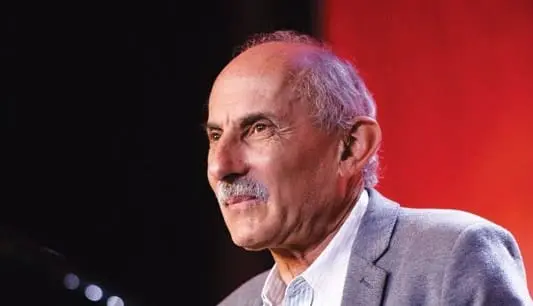

Photo by Sam Levitan

Jack Kornfield

Jack Kornfield, Ph.D., trained as a Buddhist monk in Thailand, Burma, and India and has taught worldwide since 1974. He is one of the key teachers to introduce Buddhist mindfulness practices to the West. He holds a doctorate in clinical psychology and is the co-founder of the Insight Meditation Society and of Spirit Rock Center in Woodacre, California. He has written more than a dozen books including The Wise Heart; A Path With Heart; After the Ecstasy, the Laundry; and more.