When spirituality is an area of focus in therapy, the work can be tricky. We tend to view religion as something separate and distinct from a client’s psychological functioning, or as a topic we should avoid wandering into. But is it really?

Just as people seek therapy because they long to heal a ruptured connection with a partner, a child, or themselves, many people experience distress because of ruptured connections with a spiritual tradition, their chosen faith, or a higher power. How do we help them? Do we encourage them to reach out to a pastor, rabbi, or imam? What if they’ve suffered from spiritual or religious trauma? Can we, as skilled mental health professionals, help them reconnect with God, however they conceive of a divine being?

I’ve spent nearly 10 years working at the Center for Pastoral Counseling of Virginia. Clients who want to explore spirituality often seek me out because they feel that I, as a covering Muslim woman and practicing psychotherapist, will get why and how nurturing a relationship to a higher power is important to them. But I’d argue that most therapists are already equipped with the curiosity, compassion, and training to explore the spiritual dimension of a presenting problem just as they would explore any important aspect of a client’s life.

I’ve always been interested in the interplay between spirituality, well-being, and different forms of suffering. Spiritual trauma that results from sexual abuse by religious leaders, or coercion in high-control, high-demand communities are extreme forms of this. But disconnection from God isn’t always dramatic, and it’s more common than we realize. It can happen after witnessing or experiencing violence and wondering why a deity or higher power failed to intervene. It can result from being forced to go against one’s inner wisdom by well-meaning caregivers who believe religion must be practiced only in one way, or from hearing religious terminology used to discipline or shame. The suffering of spiritual disconnection can also result from an absence of meaning or purpose within a family or culture.

When we as therapists embrace spiritual issues as within our rightful purview, we can tune into the everyday spiritual disconnection our clients struggle with and may not feel free to explore anywhere else. Sometimes, we can even help them reconnect to their faith.

I Still Want to be Muslim

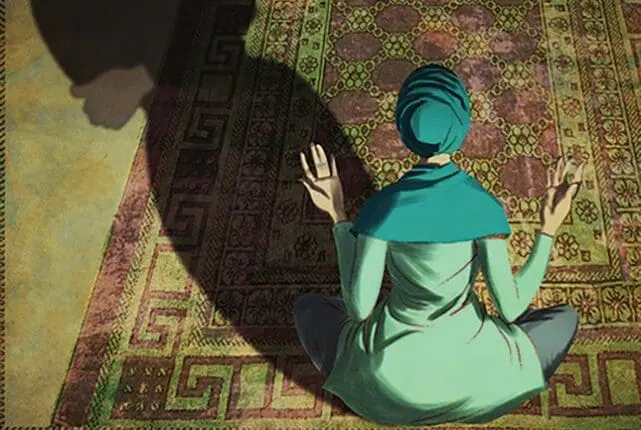

Tasleemah was a recent college graduate planning to apply to dental school. When she sat down on my sofa for our first session, she said, “I didn’t want to see a therapist who wasn’t Muslim. I didn’t want them to see me and think, Oh, here’s an oppressed Muslim woman.” She wore her hijab turban-style and stared intently at the pattern on my rug.

I half-smiled and nodded.

“The big issue in my life is that I’m not at peace. Everybody always says that when you’re a good Muslim, you’ll feel this peace. I don’t have that. I don’t get along with my parents, even though I love them both a lot.” She went on to describe years of conflicts and admitted to feeling invisible in their eyes, except when she accomplished something—whether it was bringing home straight A’s or performing in a competition at the masjid for Qur’an recitation. “I’m the oldest. I try to take care of things so my siblings don’t have to worry as much,” she continued.

I nodded again, partly because I’m also an eldest daughter of immigrant parents, and I understand this pressure.

“My parents always used to tell me that girls shouldn’t be besharam—you know, immodest—and that Allah would be mad at me if I disobeyed them. My parents were so worried about what people would think.” She picked at her nails absently. “I couldn’t do anything that my friends did, and I wouldn’t dare tell my friends about my family. It was all about obedience, and if I ever asked my parents to, like, hear my feelings, it was as if I was speaking a foreign language. Don’t get me wrong, I’m Muslim. I was active in the MSA. But it’s complicated.”

As I listened to her, I sensed the internal struggle of experiencing contradictory feelings toward her faith and upbringing. “Who is Allah to you?” I asked, opting to directly address her faith.

She gave me a quizzical look. “I mean, he’s God.”

“Like, is Allah kind? Punishing?” I smiled as I prodded her a bit. “Merciful? Vengeful?”

She slumped back in her chair and crossed her arms. Suddenly, I had a feeling that I was seeing a younger side of her. “What do you want me to say?” she responded finally.

“I want to understand how you see things.” I lowered my voice a bit, trying to convey the softness I felt for her in my heart.

Tears sprang into her eyes before she squeezed them shut, and her body shuddered. She held one arm across her chest in a half-hug and raised the other hand, as if signing stop. We sat in silence for a minute. When the intensity of the moment began receding, I observed quietly, “I notice you shuddered.”

“It happens sometimes, especially when I try to pray,” she said. “I have to kind of not be there when I make salah, or I keep shuddering.” Salah, the obligatory prayer practicing Muslims engage in five times a day, facilitates a time to pause and connect with God. For Tasleemah to say she was shuddering like this, and perhaps dissociating during prayer, was a significant revelation, one that got me wondering about the role of spiritual disconnection in her life.

Over the next few weeks, we waded into the painful feelings that came up whenever she tried to connect to Allah. She described specific scenarios, such as having difficulty attending mosque and her mixed feelings toward wearing hijab. As we spoke about the feelings these situations brought up for her, I made sure to ask what meaning she made of them. I could see that her parents’ fervor had woven pain, rejection, shame, and fear into her relationship with a higher power. We sat with each feeling, along with the guilt she felt for feeling betrayed by God. Tasleemah’s conflicting emotions were heavy and thick, sometimes suffocating; it was as if a veil had been placed between her and God. I held compassion for her parents’ intention to connect Tasleemah to faith, and I noted my own sadness that their methods did the exact opposite. Slowly, we unwound it all.

An Opening for Connection

One day, Tasleemah told me she’d been skipping prayers altogether. “I want to make sujud,” she said, “but I just can’t!”

Sujud is a position where one’s forehead, nose, hands, knees, and toes touch the floor. It’s considered a position where you’re closest to God, the ultimate act of submission and humility, the position from which all prayers will be answered.

I took a breath and consciously drew my energy downward, grounding my body in the chair. I wanted to sit alongside her in her experience of craving the deep connection offered by sujud, and of being unable to reach it. We explored how she felt the disconnect in her body, and how she might know somatically if she were to find connection. The insights she gained about how her body experienced distress and could be soothed helped her build a safe container for the next stages of our work together, which would involve attunement to deeper layers of her inner experience. Following her sensations helped me know how she was conceptualizing connection with the divine and get clearer about what therapeutic support she needed from me.

To help with her goal of reconnecting with Allah in an embodied way, I invited Tasleemah to do a bottom-up exercise I sometimes use with my Muslim clients. It builds on the principle that in Muslim cultures people call upon Allah’s various Names when making pleas during prayer. For example, if I need help in my finances, I might say, “Ar-Razzaq (The Provider, Sustainer), please help me find a way to support my family.” I may continue with, “Ar-Raheem (The Grantor of Mercy), Ar-Rahman (The Possesser of vast Mercy), may the job I get be something that I love.” With clients of other faiths, I ask about their worldview and then operate from within the framework they provide to identify a spiritually grounded statement that feels true to them, resonating in their body, which they can work on between sessions.

I took my time describing the exercise to Tasleemah, answering all her questions until it was clear she felt comfortable with it. I was careful to observe her nonverbals. Sometimes clients wish to be compliant, but their body exhibits signs of ambivalence or resistance. First, I told her, we’d use the breathing and grounding skills I’d taught her to establish a safe container. Then, I’d guide her through setting an intention for the exercise. The next step would require her to turn inward and let her body guide her internal process, which both of us would track as she recited each of the Names of Allah in Arabic and English. As she paused and breathed between Names, we’d then look for a bodily signal that one of the Names would be hers to reflect on for the week. I was half expecting her to reject my invitation to do the exercise, but instead she pulled her feet up onto the sofa and sat cross-legged, ready to try it.

Almost immediately, she had the Name of Allah that she would be reflecting on for the following week: As-Salaam, The Giver of Peace. Coincidently, this Name had the same Arabic root as her name.

The following week, upon entering my office, Tasleemah apologized profusely. “I didn’t do my homework. I was focused on school. I didn’t reflect on the Name I chose,” she said.

“It sounds like you were busy,” I noted.

“I was definitely busy,” she said, “but I felt pretty relaxed. I slept better than I have been recently. One essay I had to write was hard, but I knocked out a first draft, which felt good. Oh, and I prayed!” Her face lit up. “It was a couple days ago, and it was only once, but I did it without even thinking about it. It just came naturally. My parents were getting up to pray, and I joined them. I still had to kinda not be there for some of it, but there were parts of it where I actually felt something.” Her lips curved into a slight smile, and a hand rested on her heart as she remembered the experience.

“Do you remember the Name you picked last week?” I asked her.

“No,” she furrowed her brow. “I should have written it down.”

“It sounds like you did work on it,” I said, amused. “It was As-Salaam.”

Her eyes grew wide, and she leaned back in her chair. After a few minutes of silence, she smiled broadly, eyes glistening.

“I did work on it, didn’t I?” she said.

Relationship Transformed

Over the next few months, Tasleemah got admitted to dental school and began attending full time; she attended Muslim singles events, even though she was generally quite shy and doing so pushed her out of her comfort zone; she contemplated moving out of her parents’ house; and most importantly, she became more adept at identifying the internal and external resources she needed and could rely on when she felt anxious about a change or uncertain about the future.

She returned to the Names of Allah exercise in times of transition and stress. Sometimes she held onto one Name for several weeks; other times she announced that she was ready for another as she entered my office. It was amazing to see how she took ownership of her spiritual growth guided by her own inner wisdom, and grew excited about what would unfold. Gradually, her ability to manage her own emotions without dissociating increased, her worldview became more positive, and she seemed to feel more agency when it came to making important decisions that affected her mood, relationships, and life. Our meetings became less frequent, moving to twice a month and then monthly.

One day, I sensed a new groundedness in the way she entered my office and took her usual seat across from me. “This past month has been challenging,” she began with a laugh and a shrug.

In a clear, unhesitant voice, she told me she’d decided not to move out of her parents’ house after all. If I’d been evaluating her statement from a Western, individualistic framework, I might’ve mistaken it for a setback, but within Tasleemah’s cultural context, her choice was a testament to therapeutic progress. No longer trapped in the younger, limiting role of a confused, reactive, self-deprecating child, she was now willingly assuming the role of an adult concerned for her parents’ well-being as they aged.

Tasleemah went on to describe a conversation she’d recently had with peers who were having trouble connecting with Allah in a way that felt embodied, intimate, and concrete. We both laughed as she described how she’d felt when she realized that she was now in a place to provide mentorship to others about nurturing their spirituality. “Allah is my best friend now,” she said in a voice that conveyed both awe and confidence.

My eyes filled with tears. She’d found what she’d been looking for: peace.

Case Commentary

By Lisa Ferentz

I applaud Fatima Mirza’s courage and creativity in recognizing the importance of exploring a client’s spirituality or religious affiliation, and understanding the impact it can have by either exacerbating trauma or playing a significant role in the healing journey. I appreciate her generous statement that most therapists have the compassionate ability to not only work with the bio-psychosocial aspects of their clients’ issues, but the spiritual aspects as well.

Many clinicians from my generation were taught to avoid any discussion related to a client’s religion. This did a terrible disservice to clients and the treatment process. Early in my career, I learned that many clients had been emotionally tortured by rigid religious dogma designed to evoke guilt and shame by framing normal thoughts, questioning, and feelings as sinful or blasphemous. I encountered many clients who’d been sexually abused by clergy, both rabbis and priests. In addition to the inevitable cognitive, emotional, and behavioral sequelae that comes from sexual abuse, feeling betrayed by God, being robbed of comforting religious rituals, and feeling forced to disconnect from spiritual and religious affiliation deepened their trauma, and left many feeling untethered in the world. Mirza’s approach to her client in this case makes so much sense because she understood the importance of allowing the client to question and redefine her concept of God. Mirza also created an unconditional and safe space for her client to slowly reclaim a religious and spiritual practice that genuinely resonated for her. I’ve learned from trauma-informed clergy that the way we define our concept of a higher power is directly related to our earliest experiences with powerful authority figures, typically our caretakers. This client bravely alludes to parents who, although well-meaning, were also critical, judgmental, and shaming. Rather than supporting their daughter’s organic and authentic connection to her religion and her relationship with Allah, her observance was rooted in obligation, fear, and obedience.

By asking the client, “Who is Allah to you?’ Mirza welcomed an exploration of the client’s concept of God and was able to connect that definition to the parental messages that conflated religion with terror, pain, and the possibility of disappointment and rejection. Mirza also gave her client permission to redefine her concept of God on her own terms and in ways that would be loving and supportive, rather than shaming.

I also appreciate Mirza’s willingness to work somatically, both to enhance a sense of safety through grounding and breathwork, and to help her client experience the embodiment of spirituality and religious connection through a “felt sense.” This helped the client to experience the comfort that one can and should derive from their relationship with a higher power, and also helped to make her religious observance truly her own. The fact that she was then able to pay it forward and offer the same encouragement and wisdom to her Muslim friends is a beautiful example of shifting from PTSD to the spiritual change that can be emblematic of post-traumatic growth.

ILLUSTRATION BY SALLY WERN COMPORT

Fatima Mirza

Fatima Mirza, PhD, LCSW, is a licensed clinical social worker working with diverse clients who are searching for meaning and healing. Contact: fatima@sunflowerinitiative.org.

Lisa Ferentz

Lisa Ferentz, LCSW-C, DAPA, is a recognized expert in the strengths-based, de-pathologized treatment of trauma and has been in private practice for more than 35 years. She presents workshops and keynote addresses nationally and internationally, and is a clinical consultant to practitioners and mental health agencies in the United States, Canada, the UK and Ireland. In 2009 she was voted the “Social Worker of Year” by the Maryland Society for Clinical Social Work. Lisa is the author of Treating Self-Destructive Behaviors in Trauma Survivors: A Clinician’s Guide, 2nd Edition (Routledge, 2014), Letting Go of Self-Destructive Behaviors: A Workbook of Hope and Healing (Routledge, 2014), and Finding Your Ruby Slippers: Transformative Life Lessons From the Therapist’s Couch (PESI, 2017).