Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

The skinny streets of Dharamsala in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh, where the Dalai Lama lives with his Tibetan government in exile, are carved along a steep mountain slope. Crowded with people and animals and clogged with sputtering vehicles, the streets rise and dive between thatched stalls of vendors selling scarves and beads, curry and tea. Across a deep valley, peaks green and brown in the summer march toward the horizon. The bright colors of this daytime scene, however, are shadowed by the dark terrors of flight that haunt the refugee Tibetans.

Recently, I was invited to Dharamsala by the Men Tsee Khang Institute, a school of traditional Tibetan medicine sponsored by the Dalai Lama, to give a talk on the scientific basis of the mind–body connection and the techniques of self-care and mutual help that my colleagues and I at The Center for Mind-Body Medicine are using with war- and disaster-traumatized populations. In my talk, I described the ingredients of our approach: several forms of meditation; biofeedback; guided imagery; self-expression in words, drawings, and movement; and small-group support. I presented evidence that shows people who participate in 10 weekly mind–body skill groups reduce their level of post-traumatic stress disorder by as much as 80 to 90 percent. I emphasized to the audience—250 Tibetan doctors, Buddhist monks, and academics—that I believe anyone can learn and use our approach, and explained that our work—in Kosovo, Israel, Gaza, Haiti, and the United States—has been implemented by local clinicians, teachers, and community leaders whom we’ve trained.

When I’d accepted the invitation to give this talk, I’d said that I also wanted to lead a workshop for recent refugees. It felt important, if I were going to make the long trip, to give more to the community than an academic lecture. So after an audience with the Dalai Lama—who held my hand and expressed his abiding appreciation for the marriage of Western psychology and Tibetan Buddhism—I had the opportunity to lead a workshop for teenagers at The Transition School. The students here, many of whom had grown up illiterate on remote Tibetan farms, had fled Tibet in recent years and were now beginning to make their transition into the larger Indian community.

—–

On a bright but chilly morning, after a breakfast of dosas and chai, Sonam Dolma, the physician who’d organized the academic conference and would serve as my translator, guides me into the school’s auditorium, where 200 teenagers, all in white jackets, are kneeling in rows on mats. I’ve done this kind of workshop dozens of times, in freezing bombed-out schools in postwar Kosovo, in the shelled city of Sderot in southern Israel, and most recently with Syrian refugees in Jordan. Almost always it’s part of a larger program, a way for the people we hope to train—teachers, religious leaders, and clinicians—to get to know our work and me, and for me to begin to feel connected to the kids they serve and to them. But it’s a little different in Dharamsala since I’m not sure whether they need our program here, and I have no plans or money to start one.

I begin my workshop with an old Indian story involving a saddhu, one of the orange-robed Indian holy men who wander the country praying and are often viewed as teachers. The story goes like this: one day, many years ago, the people in a small town heard that a saddhu was nearby. Some villagers went out to ask him to come to speak to them. He came reluctantly to where the entire village had assembled.

“How many of you know what I’m going to say?” he asked. The villagers looked at each other in bewilderment. How could they possibly know? “Idiots!” the saddhu shouted. “You don’t know anything. I’m leaving.” The villagers were insulted but also intrigued, so they sent out another delegation to ask the saddhu to come back. Grumbling, he returned.

“How many of you know what I’m going to say?” he asked again. This time all the villagers raised their hands. The saddhu looked at them and said, “If you already know what I’m going to say, why should I bother talking to you?” He stomped away.

Now the villagers were really intrigued. They put their heads together and figured out what to do next. This time they sent out a delegation of all the elders. “Please,” they begged the saddhu, “come back. We really want to hear what you have to say.” Cursing, the saddhu allowed himself to be brought back to the village.

Once again he asked, “How many of you know what I’m going to say?” The villagers, having carefully prepared, believed they knew what to do. Half of them raised their hands, and the other half kept their hands down. “Ahh,” said the saddhu, looking out over the assembly with a smile, “those who know can tell those who don’t. I’m leaving.”

“The point of the story,” I tell the kids, who are laughing now, “is that we may think we don’t have the answers, but each of us has a part inside us that knows. One of the most important ways we can use this inner knowing is to help us relieve stress.” Slowly, I go on to explain to them the biology of the fight-or-flight response, with Sonam carefully translating as I pause periodically. I talk about how our fast heart rate and breathing, our dilated pupils, the blood rushing away from our skin and filling our large muscles all make it possible to fight an enemy or run away. “Fight or flight is a survival response,” I say. “It’s crucial, lifesaving.” Many of the kids nod their heads in agreement, remembering, I imagine, their own flight and the Chinese soldiers who pursued them. “The problem,” I continue, “is when fight or flight goes on too long, when weeks or months or even years after the threat is over and you’ve escaped, your body is still acting like it has to fight or run. Then you become tense when you don’t need to be. You feel your heart racing, can’t study, have stomach and head pains. How many of you have experienced the fight-or-flight response?” I ask. Everybody’s hand goes up. Then I pose the key question: “How many of you are still feeling it?” Well over half the kids have their hands in the air. “Now,” I go on, “I’m going to show you how to quiet the fight-or-flight response, to deal with stress when it comes up.”

I ask them to sit comfortably and breathe deeply—in through the nose and out through the mouth, with bellies soft and relaxed. I suggest that they close their eyes to block out as much external stimulation as possible, and explain that when the belly is soft and relaxed, more air comes into the lower part of the lungs and more oxygen enters the bloodstream. I tell them that oxygen feeds our brains and all our body’s cells and that a soft belly helps activate the vagus nerve, which promotes relaxation and is the antidote to fight or flight. “When your bellies are soft,” I say, “all the other muscles in your body can relax as well. To help achieve this, you can say to yourself ‘soft’ as you breathe in and ‘belly’ as you breathe out. If thoughts come, let them come and let them go. Gently bring your mind back to ‘soft belly.’” We do this for six or seven minutes, and then I ask the kids to open their eyes and bring their attention back into the room.

“How many of you noticed a change?” I ask. At least 80 percent of them raise their hands. “What kind of change?” I want to know and pick a few eager students to answer.

When I point to her, one girl calls out, “Calmer.”

“Brighter colors in the room,” another girl says.

“I’m smiling,” offers a boy in the middle of the room.

“Good,” I say. “This means that most of you can relax the first time you do this, in just six or seven minutes. This tells you that relaxation is possible and, even more importantly, that you can make it happen yourself. And if you’re one of those who doesn’t feel more relaxed, don’t worry, it’ll probably happen next time.”

Next, I want to talk a little bit about trauma, and as I look out at the faces of these children, who’ve left their homes and their sense of place behind under violent, frightening circumstances, I take a deep breath myself. “Sometimes,” I say, “when we feel overwhelmed and trapped, when we can’t fight or run away, we may, as a last-ditch effort of survival, freeze in terror, or even collapse.” I ask if they’ve ever seen a cat playing with a mouse, swatting it, biting it, shaking it in its teeth. “Have you noticed that sometimes the mouse looks dead, but when the cat loses interest in it, the mouse suddenly turns over and scurries away on its little legs? That’s freezing and unfreezing. Have any of you ever frozen?” I ask. Most of their faces become serious, reflective. Perhaps 40 or 50 hands go up. “Sometimes when we’re terrified and unable to do anything, our bodies feel so tense that our minds can’t work. We feel heavy, weighed down. It’s as if we’re trapped, physically and emotionally. And when this continues for days or weeks, we need to shake ourselves out of this trap in our bodies and minds. The best, easiest way to do this is to shake our bodies. So let’s stand up,” I say, my voice rising like a coach’s.

The kids look puzzled and apprehensive, and I wonder, as I always do, Are they going to go for it, get into it?

“Here’s how you shake,” I continue, and standing on the stage, I begin to bounce on my feet, letting the movement rise up through my knees and hips to my shoulders and head. A wave of laughter erupts through the auditorium and I smile widely. “Yes, I know I look a little crazy, but that’s okay. I have a feeling that if you do it too, if you let yourself be a little crazy, you’ll feel as good as I do up here.”

Looking at one another, laughing at the sudden goofiness, they stand up. “We’ll do shaking to fast music for five or six minutes,” I tell them. “Then we’ll stop and stand and be aware of our body and breath. Then the music will change. When it does, let it move you. This doesn’t mean you have to ‘dance.’ The idea is for your body to move, to express itself freely in whatever way it needs to. This is a fun experiment, but there’s one condition: you have to close your eyes so you won’t peek at anyone else.” They laugh again at my invitation to suspend their normal self-consciousness.

I put on fast, electronic music, and they begin to shake with me. They’re tentative at first, then, as I shout encouragement—“Good! Yes! Let go of the tense shoulders!”—they speed up the pace and begin to let their limbs and heads flop around with the beat. After five or six minutes, I turn off the music and instruct them to relax and observe their body and breathing. Then comes different music—Bob Marley’s “Three Little Birds.” The kids start to move again, slowly this time. Most simply sway back and forth. Some raise their arms. “Let the music move you,” I say. “There are 200 of you, and each of you will move in the way that’s just right for you.”

Afterward, many of the kids are smiling. “How do you feel?” I ask.

“I feel more relaxed,” says a slim young girl.

“Less worried,” adds a boy at the back of the room as his classmates nod in agreement. Questions follow about how to practice on their own and what kind of music to use.

“Something upbeat,” I answer. “Something that inspires you. And if you’re going to do the quiet, soft-belly breathing I taught you, do it after the shaking and dancing. You’ll get rid of your tension, and it’ll be easier to sit and relax.”

After I finish, the kids applaud, and Sonam tells them that anyone who wants to can have an individualmeeting with me. We hadn’t arranged this ahead of time, but Sonam whispers to me that many of the kids are deeply troubled and need more help. I don’t usually do individual consultations because our goal is to equip local people—clinicians, teachers, and other leaders—to help the population. It runs counter to our approach for the “big Western doctor” to come up with answers to individual problems. But I don’t want to disappoint or be rude to my hosts. Maybe it’ll be fine, I think, not expecting more than a couple of kids to respond to her invitation. To my surprise, more than 20 of them line up to talk with me.

I first speak with an 18-year-old boy whose black hair falls across his broad forehead. He’s had “terrible neck pain” following a fall during his escape. Having been trained by osteopaths, I can feel the shift in his cervical vertebrae. Using my hands to manipulate his head and neck, I put the bones back in place. “Do the shaking and dancing to stay loose. And get one of your buddies to massage your neck and shoulders regularly,” I tell him. “That will relax the muscles so the bones can stay in place.”

Next, a 15-year-old girl whose narrow pale face is clenched in pain tells me she is “so lonely” for her family and anxious about the revenge the Chinese may exact on them because of her flight. I prescribe soft-belly breathing and frequent sharing of her frightening feelings with her friend, who’s standing behind her in line.

The consultations seem to be helping, but I worry it’ll take far too long to get to everyone. There’s also something more important nagging at me: I don’t like the image or the feeling of being the expert bringing cures or dispensing advice. Instead, I want these kids to feel they have some tools they can use for themselves.

“I know we promised individual consultations,” I say, “but there are so many of you, and I think there’s a better way. Let’s get in a circle and form a group. I’m going to teach you to go in your mind to a safe, peaceful place. And then I’m going to help you find a wise guide inside yourself who can answer the questions that you have. As a bonus, you’ll be able to learn from each other.”

I’d been warned that Tibetan children tend to be shy and that the culture doesn’t easily allow for sharing of feelings. Still, I’m pretty sure this small-group exercise will work. After all, it’s worked in other places where emotions are customarily concealed. When they know they’re not going to be mocked or reported, for instance, US combat veterans feel comfortable sharing, shouting, and crying in a small group of peers. In Gaza, abused, veiled women have overcome the silence their culture teaches them and shared their pain with one another, often finding the strength and courage to stand up to their husbands.

In Dharamsala, I put on Native American flute music and ask the kids to close their eyes. Once again, I begin with soft-belly breathing. After a few minutes, I say, “Now, let the sound of the music and the sound of my voice take you to a country road. As you walk down that road, notice what you see, hear, feel, smell, and think.” After a few minutes more, I suggest that they come to a place that’s safe or special for them. “This is somewhere you can go when you’re feeling anxious or troubled,” I explain. “It can be a place you know or remember or one that just comes to you now.” I tell them to take their time and notice how the place looks, feels, and smells. “What sounds are there? What clothes are you wearing in this place?” I prompt.

After they’ve had time to settle into this safe place, I suggest that a wise guide will appear—a human or an animal, a relative or a friend, or a figure from scripture or books. This guide represents the part of them that knows what their conscious mind doesn’t. It’ll answer the questions that trouble them, and tell them what they need to know to feel better, more secure and happy. After they’ve had time to silently ask their guides questions and receive their answers, I guide them slowly back down the country road and into the room where we’re sitting. I then invite them to share their experiences.

I’ve done this exercise hundreds of times. Sometimes, particularly with victims of war and refugees living in stifling or frigid tents, the safe place is hard to locate and, on first try, the guide seems elusive. But never have the country roads been as treacherous as the ones these young people have envisioned. They’re rutted, steep, narrowing at bridges, flanked by sheer drops, obscured by forests, concealed from the sun. Even so, many of the kids report that these roads led them to surprisingly friendly, safe places—a welcoming familiar home they’d left behind in Tibet, meadows high in the mountains bright with birds and flowers. The guides that appeared to some—birds, grandparents, best friends—provided answers and gave directions the kids find reassuring.

One girl recounts how she asked her guide, a graceful deer, why she couldn’t appreciate beauty after leaving Tibet. She says the guide told her, “You can’t be happy with beauty now because it reminds you of what you lost. Even if you find the most beautiful place, you’ll still feel lonely unless you find peace inside.”

A boy relays that his guide, who looked like the kind father he’d left behind, told him, “You’ll have to cross many difficult bridges in this new land.”

At one point, a solemn, stocky young man says he wanted to ask his guide how he could relieve the pains in his joints and banish his nightmares. For two years before he escaped, he says, he was regularly hung by his arms from the ceiling and beaten in freezing Chinese prisons. “When I closed my eyes just now,” he continues sadly, “I saw a butterfly, but I wanted a monk as my guide, and he would not come.”

“How did the butterfly make you feel?” I ask.

“Happy,” he answers with a slight, surprised smile.

“Why did you want to see a monk?” I ask.

“Because monks are wise,” he replies.

“Yes,” I say, sad that the real monks in Dharamsala haven’t been able to help more, but hopeful that he’ll be able to find comfort and strength within. “Next time, try asking the butterfly what to do. Perhaps she’ll have an answer.”

Before we sit quietly to close the session with soft-belly breathing, the kids ask when I’ll return. Suddenly, I find myself in tears. I hadn’t planned to return, but these kids—so sweet, tender, and brave, so open to shaking and dancing with me, and looking into themselves and sharing with me—have opened my heart. “Soon,” I find myself saying, wondering how I’ll make it happen. “In the meantime, you can keep on doing soft-belly breathing and shaking and dancing. And you can keep going down the road to find that safe place inside you that gives you peace. Meet your guides and let them be your teachers. Share what you learn with others, the ones in our circle here and everyone else,” I say, gesturing toward the walls of the school and the kids in the yard outside.

As I return to the crowded streets of Dharamsala beyond the school walls, I hope that this experience of loving self-care stays with these children, who’ve already gone through so much, so early in their lives, and that, whatever happens, they find a way to maintain their connection with the guides they’ve just discovered and the invaluable gifts they’ve revealed—the wealth of their own inner wisdom.

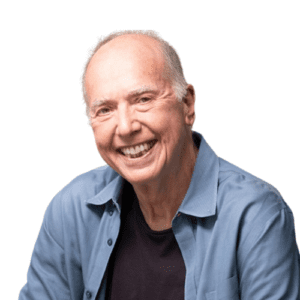

James Gordon

James S. Gordon, MD, is a psychiatrist, the founder and CEO of The Center for Mind-Body Medicine, and the author of Transforming Trauma: The Path to Hope and Healing. He is a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Family Medicine at Georgetown Medical School and chaired the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy. His work with war-traumatized children in Gaza and Israel, both of which he has visited 20 times, has been featured on 60 Minutes in 2015, as well as in The New York Times and The Washington Post.