We Americans believe profoundly not only in the pursuit of happiness, but in our unalienable right to obtain it. Despite roughly 5,000 years of written evidence to the contrary, we believe it isn’t normal to be unhappy. That’s why we have so many approaches to therapy and so many therapists. In general, we don’t want to stick around with psychological pain a second longer than necessary to get it excised from our life.

The problem is, according to Steven Hayes, professor at the University of Nevada, former Haight-Ashbury hippie turned behaviorist, and the developer of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), we’ve got it backwards. In fact, it’s suffering and struggle that are normal—and not the reverse. Furthermore, dealing with our inevitable psychic struggles by trying to get rid of them doesn’t work and may actually make them worse.

Instead of countering and correcting our negative thoughts, as classic cognitive therapy argues we should do, Hayes believes we should acknowledge those thoughts, accept them rather than challenge them, and then get on with living as full and worthwhile a life as we can. That’s the commitment part of ACT, and the tough-minded part as well. Hayes has stated elsewhere, “When we learn how to just notice our depressive thoughts and feel our feelings as feelings, deliberately and fully, it turns out that we can begin to live again, right now, even with depressed feelings or depressogenic thoughts. And when we do that, we start to move. We’re able to contribute to others and to make a difference.”

In his prodigiously well-published career, Hayes has written more than 500 scientific articles and several books, including the 2005 bestseller Get Out of Your Mind and Into Your Life, and has established ACT as the most empirically supported application of mindfulness principles in the field of psychotherapy. In the following interview, he explains both the origins of ACT and what he sees as its future.

***

RH: How did you first develop ACT?

Hayes: ACT was first developed in the early ’80s and grew out of my own experience with panic disorder and treating other clients with anxiety problems. Although I was a child of the ’60s and had lived in an Eastern religious commune, I’d been trained as a cognitive behavioral therapist. When I realized that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) wasn’t helping me deal with my own problems with anxiety, I returned to some of the more Eastern ideas that had appealed to me earlier in my life. I began to explore certain fundamental principles that underlie many contemplative spiritual traditions.

If you either avoid something or fight and argue with it, you give it power. Instead, I began to see how to apply meditative and mindfulness practices to my anxious thoughts and feelings about myself. I added the idea of examining a person’s deepest values as a guide to determining the direction of change. It’s not enough to focus on what you don’t want to experience. If I don’t focus on my symptoms, what do I want to be doing with my life? That’s where the role of commitment came into ACT.

From the beginning, it was also important that this approach be guided by the discipline of evidence-based science. In the early ’80s, we did trials comparing ACT against best-of-breed CBT approaches and found that whether the problem was weight control, depression, or panic, ACT did as well as or better than anything that was available at the time.

RH: What’s distinctive about what mindfulness contributes to psychotherapy?

Hayes: Mindfulness methods show us how a focus on the content of problems can get in the way of effective therapy. It’s not what you feel and think that matters nearly so much as how you relate to what you feel and think. Of course, that’s the essence of contemplative practices in which you watch thoughts and feelings rise and fall. Applying that perspective within the scientific tradition of evidence-based therapies hadn’t been done before. The more obvious reason that mindfulness has been transformational is that it’s shown how a range of processes like nonjudgment, experiential openness, and flexible attention impact the common symptoms people bring into psychotherapy.

RH: Let’s make it practical here. Say you’re working with someone with panic disorder. What’s the ACT treatment plan?

Hayes: We view anxiety as a problem of psychological inflexibility. It’s an inability to come into the present moment and open up to your emotions, to see your thoughts as they are, and to focus on what’s really of importance to you. The goal of ACT is to help people develop a sense of self that’s larger than the limited story they’re used to telling about themselves and others that’s getting in their way.

When ACT works, it helps people get more in touch with their thinking and feelings as they are—not what they’re supposed to be. And instead of experiencing emotions as accidents or obstacles, people can understand their meaning and use them to move toward what gives them more energy and purpose in life. ACT isn’t a panacea or a cure, but it’s a way to organize your life around a fuller sense of purpose and meaning, one step at a time.

RH: What are the practical applications of ACT techniques?

Hayes: It turns that ACT methods apply to a stunning range of human problems and opportunities for growth. As of the end of 2014, there’ve been more than 110 randomized controlled trials of ACT and 260 total trials in almost every area of human concern. Areas with at least five published studies are what you’d expect—depression, anxiety, substance use, pain control—but others are perhaps more surprising: psychosis, stigma and prejudice, training and education, dealing with cancer.

ACT has been shown to help international-level chess players and professional hockey players. There are Olympic athletes who’ve won their gold medals using ACT. How can a therapy method achieve all that? The key seems to be improving psychological flexibility—people’s openness to experience and their ability to disentangle from distracting cognition and feelings. By increasing people’s ability to purposefully attend to the present and their ability to link their actions to their deepest values, you can put them on a path to positive growth that will likely echo for a long time, not just in their lives, but in the lives of those they love.

RH: Are there any problems ACT is unable to address?

Hayes: Two areas stand out. First, if you have minor issues like a specific phobia, it may be better just to use behavioral methods alone, such as exposure and applied relaxation, without the ACT wraparound. ACT raises deeper issues of emotion, thought, values, and sense of self that may seem superfluous to someone with short-term behavioral goals. If you run into problems with simpler methods in these cases, ACT can then be brought in to help overcome these barriers. For example, ACT has been shown to help increase willingness to undergo exposure.

Second, prevention using an ACT model is a work in progress. We’re still learning how to reach people with transformational messages that are outside the cultural mainstream when they’re not in any difficulty psychologically. For example, ACT teaches the need to embrace psychological pain in order to live more flexible lives. It encourages people to define themselves as conscious awareness and not a list of achievements. This helps people avoid the aloneness and narrowness of a defense of the conceptualized self, or the “ego.”

These are important, teachable messages, and we know from research that acquiring such psychological flexibility will produce large benefits going forward. But young people in particular sometimes believe that they have the world by the tail, even if they’re doing things—such as avoiding feelings or buying into self-judgments—that will eventually have considerable negative cost to them.

Large longitudinal studies show that greater psychological flexibility will reduce mental health problems and the development of comorbidities, but merely telling people that isn’t enough. We have to learn how to reach people with psychological-flexibility messages and skills before there’s an obvious need for them. I think it’ll take a lot of creativity from a lot of people to overcome this challenge.

RH: ACT has been described, along with other mindfulness approaches, as part of behaviorism’s third wave. Is there a fourth wave ahead for our field?

Hayes: Well, probably. People like the notion of waves. But waves and a radical change in underlying assumptions about how people change and how therapy should work tend to be generational. You can’t force the process. It happens organically and naturally, with a lot of people shifting their perspectives. For now, it’s fascinating to explore what we can accomplish with the powerful combination of these ancient wisdom traditions and process-oriented empirical science. It’ll be fun to see how together they can make a difference in the lives of the people we serve.

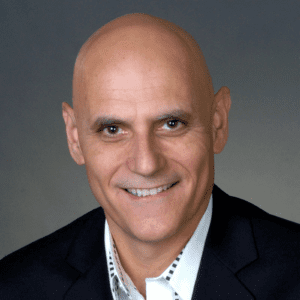

Steven Hayes

Steven C. Hayes, PhD, is the co-founder of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), best-selling author of Get Out of Your Mind and Into Your Life and Nevada Foundation Professor at the Department of Psychology at the University of Nevada. An author of 44 books and nearly 600 scientific articles, he has shown in his research how language and thought leads to human suffering, and has developed ACT as a way of correcting these processes. Hayes has been president of several scientific societies and has received several national awards, such as the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies.

Ryan Howes

Ryan Howes, Ph.D., ABPP is a Pasadena, California-based psychologist, musician, and author of the “Mental Health Journal for Men.” Learn more at ryanhowes.net.