Charles, a personable business executive, had the right stuff behind him: a sterling education at Andover, Harvard, and Harvard Business School; a grandfather and father who were successful bankers; and a mother who was head of the board of trustees of an eminent women’s college. And the right stuff around him: a San Francisco condo with a panoramic view from Golden Gate to the Bay Bridge; a lovely, socially prominent wife; a mid-six-figure salary; and a Jaguar XKE Convertible. And all of this at the advanced age of 37.

Yet he had no right stuff inside. Choked by self-doubts, recriminations, and guilt, Charles always perspired when he saw a police car on the highway. “Free-floating guilt searching for a sin—that’s me,” he joked. Moreover, his dreams were relentlessly self-denigrating: he saw himself with large weeping wounds, cowering in a cellar or cave; he was a low-life, a lout, a criminal, a fake. But even as he demeaned himself in dreams, his quirky sense of humor shone through.

“I was waiting in a group of people who were auditioning for a role in a film,” he told me, describing a dream in one of our early sessions. “I waited my turn and then performed my lines quite well. Sure enough, the director called me back from the waiting area and complimented me. He then asked about my previous film roles, and I told him I’d never acted in a film. He slammed his hands on the table, stood up, and shouted as he walked out, ‘You’re no actor. You’re impersonating an actor.’ I ran after him shouting, ‘If you impersonate an actor, you are an actor.’ But he kept on walking and was now far in the distance. I screamed as loudly as I could, ‘Actors impersonate people. That’s what actors do!’ But it was pointless. He’d vanished, and I was alone.”

Charles’s insecurity seemed fixed and unaffected by any sign of worthiness. All positive things—accomplishments, promotions, and messages of love from wife, children, and friends; great feedback from clients or employees—passed quickly through him like water through a sieve. Even though we had, in my view, a good working relationship, he persisted in believing that I was impatient or bored with him. I once commented that he had holes in his pockets, and that phrase resonated so much that he repeated it often during our work. After hours of examining the sources of his self-contempt and scrutinizing all the usual suspects—lackluster IQ and SAT scores, failure to fight the elementary school bully, adolescent acne, awkwardness on the dance floor, occasional premature ejaculations, worries about the small size of his penis—we eventually arrived at the primal source of darkness.

“Everything bad began,” Charles told me, “one morning when I was 8 years old. My father, an Olympic sailor, set out on a gray windy day on his regular morning sail in a small boat from Bar Harbor, Maine, and never returned. That day is fixed in my mind: the horrendous family vigil, the growing angry storm, my mother’s relentless pacing, our calls to friends and the Coast Guard, our fixation on the telephone resting on the kitchen table with a red-checkered tablecloth, and our growing fear of the shrieking wind as nightfall approached. And worst of all was my mother’s wailing early the next morning when the Coast Guard phoned with the news that they’d found his empty boat floating upside down. My father’s body was never found.”

Tears streamed down Charles’s cheeks, and emotion choked his voice as if the event had happened yesterday, rather than 28 years ago. “That was the end of the good days, the end of my father’s warm bear hugs and our games of horseshoes and Chinese checkers and Monopoly. I think I realized at the time that nothing would ever be the same.”

Charles’s mother mourned the rest of her life, and no one ever came along to replace his father. In his view, he became his own parent. Yes, being a self-made person had its good points: self-creation can be powerfully reaffirming. But it’s lonely work, and often, in the dead of night, Charles ached for the warm hearth that had grown cold so long ago.

A year ago, at a charity event, Charles met James Perry, a high-tech entrepreneur. The two became friendly, and after several meetings, James offered Charles an attractive executive position in his new start-up. James, 20 years older, possessed the Silicon Valley golden touch, and though he’d accumulated a vast fortune, he could not, as he put it, get out of the game, so he continued to launch new companies. Although their relationship—friends, employer and employee, mentor and protégé—was complex, Charles and James negotiated it with grace. Their work required considerable travel, but whenever they were both in town, they never failed to meet at the end of the day for drinks and conversation. They talked about everything: the company, the competition, new products, personnel problems, their families, investments, movies, vacation plans, whatever crossed their minds. Charles cherished those intimate meetings.

It was then, soon after meeting James, that Charles first contacted me. Paradoxical though it might seem to seek therapy during a halcyon time of nurture and mentorship, there was a ready explanation. The caring and fathering he received from James stoked Charles’s memory of his father’s death and made him more aware of what he’d missed.

During our fourth month of therapy, Charles called to request an urgent meeting. He appeared in my office with an ashen face. Walking slowly to his chair and lowering himself carefully, he managed to utter two words, “He’s dead.”

“Charles, what happened?”

“James is dead. Massive stroke. Instant death. His widow told me she’d had a dinner meeting with her board and came home to find him slumped in a living room chair. Christ, he hadn’t even been sick! Totally, totally unexpected.”

“How awful. What a shock this must be for you.”

“How to describe it? I can’t find the words. He was such a good man, so kind to me. I was so privileged to know him. I knew it! I knew all the while it was too good to last! Boy, I really feel for his wife and kids.”

“And I feel for you.”

Over the next two weeks, Charles and I met two to three times a week. He couldn’t work, slept poorly, and wept often during our sessions. Again and again he expressed his respect for James and his deep gratitude for the time they had shared. The pain of past losses resurfaced, not only for his father but also his mother, now three years and one month dead. And for Michael, a childhood friend who died in the seventh grade, and for Cliff, a camp counselor who died of a ruptured aneurism. Over and again Charles spoke of shock.

“Let’s investigate your shock,” I suggested. “What are its ingredients?”

“Death is always a shock.”

“Keep going. Tell me about it.”

“It’s self-evident.”

“Put it into words.”

“Snap, life is gone. Just like that. There’s no place to hide. There’s no such thing as safety. Transiency . . . life is transient. I knew that. Who doesn’t? But I never thought much about it. Never wanted to think about it. But James’s death makes me think of it. Forces me to, all the time. He was older, and I knew he’d die before me. It’s just making me face things.”

“Say more. What things?”

“About my own life. About my death that lies ahead. About the permanence of death. About being dead forever. Somehow that thought, being dead forever, has gotten stuck in my mind. Oh, I envy my Catholic friends and their afterlife stuff. I wish I could buy into that.” He took a deep breath and looked up at me. “So that’s what I’ve been thinking about. And also lots of questions about what’s really important.”

“Tell me about that.”

“I think about the pointlessness of spending all my life at work and of making more money than I need. I’ve got enough now, but I keep on going. Just like James. I feel sad about the way I’ve lived. I could’ve been a better husband, a better father. Thank God there’s still time.”

Thank God there’s still time. I welcomed that thought. I’ve known many who’ve managed to respond to grief in this positive fashion. The confrontation with the brute facts of life awakened them and catalyzed some major life changes. It looked as though that might be true for Charles, and I hoped to help him take that direction.

A Cyclone of Feelings

About three weeks after James Perry’s death, Charles entered my office in a highly agitated state. He was breathing fast, and to calm himself, he put his hand to his chest and exhaled deeply as he slowly sank into his seat.

“I’m really glad we’re meeting today. If we hadn’t had this time scheduled, I probably would’ve phoned last night. I’ve just had one of the biggest shocks of my life.”

“What happened?”

“Margot Perry, James’s widow, phoned me yesterday to invite me over because she had something she wanted to talk about. I visited her last evening and . . . well, I’ll get right to the point. Here’s what she said: ‘I didn’t want to tell you this, Charles, but too many people know now, and I’d rather you hear it from me than from someone else. James didn’t die from a stroke. He committed suicide.’ And since then I can’t see straight. The world’s turned upside down.”

“How terrible for you! Tell me all that’s going on inside.”

“So much. A cyclone of feelings. It’s hard to track.”

“Start anywhere.”

“Well, one of the first things that flashed in my mind is that If he can commit suicide, then so can I. I can’t explain this any further except that I knew him so well and we were so close and he was like me and I was like him and if he could do that, if he could kill himself, then I can too. That possibility shook the hell out of me. Don’t worry—I’m not suicidal—but the thought lingers. If he could, then so can I. Death, suicide: they aren’t abstract thoughts. Not any longer. They’re real. And why? Why did he kill himself? I’ll never find out. His wife is clueless, or pretends to be. She said she was totally caught by surprise. I’ll have to get used to never knowing.”

“Keep going, Charles. Tell me everything.”

“The world is upside down. I don’t know what’s real anymore. He was so strong, so capable, so supportive of me. So caring, so thoughtful, and yet, think about it, at the same time he was making a cozy nest for me, he must have been so agonized he didn’t want to exist any longer. What’s real? What can you believe? All those times he was giving me support, giving me loving advice, at the same time he must have been contemplating killing himself. You see what I mean? Those wonderful blissful times when he and I sat talking, those intimate moments we shared—well, now I know those times didn’t exist. I felt connected, I shared everything, but it was a one-man show. He wasn’t there. He wasn’t blissful. He was thinking of offing himself. I don’t know what’s real anymore. I’ve fabricated my reality.”

“How about this reality? This room? You and me? The way we are together?”

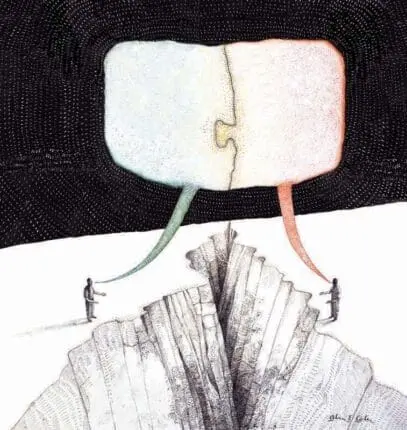

“I don’t know what to trust, who to trust. There’s no such thing as a ‘we.’ I’m truly alone. I doubt very much that you and I are experiencing the same thing this very moment, right now as we speak.”

“I want us to be a ‘we’ as much as possible,” I said. “There’s always an unbridgeable gap between two people, but I want to make that gap as small as possible here in this room.”

“But Irv, I’m only guessing what you think and feel. And look how wrong I was about James. I guessed we were doing a duet, but it was a solo number. I’ve no doubt I’m doing the same here, guessing wrong about you.” Charles hesitated and then suddenly asked, “What are you thinking right now?”

Twenty or thirty years ago such a question would have truly rattled me. But as I’ve matured as a therapist, I’ve grown to trust my unconscious to behave in a professionally responsible manner, and I know full well that it’s not so much what I say about my thoughts that’s important but rather that I’m willing to express them. So I said the first thing that came into my mind.

“My thought at the moment you asked that question was very odd. It was something I saw recently posted on an anonymous website for secrets. It read, ‘I work at Starbucks and when customers are rude I give them decaf.’”

Charles looked up at me, stunned, and then suddenly erupted into laughter. “What? What’s that got to do with anything?”

“You asked what I was thinking, and that’s what popped into my mind: that everyone has secrets. Let me try to track it. That train of thought started a couple of minutes earlier, when you spoke of the nature of reality and how you fabricate it. And then I started thinking of how right you are. Reality isn’t just something out there but something each of us constructs, or fabricates, to a significant degree. Then, for a moment—bear with me; you asked what I was thinking—I thought of the German philosopher Kant and how he taught us that the structure of our minds actively influences the nature of the reality we experience. And then I started thinking of all the deep secrets I’ve heard over my half century of practice as a therapist and reflecting that, however much we crave to merge with another, there will always remain distance. Then I started to think of how your experience of the color red or the taste of coffee and my experience of ‘red’ and ‘coffee’ will be very different in ways we can never really know. Coffee—that’s it; that’s the link to the Starbucks secret. But sorry, Charles, I’m afraid I’m wandering far from where you may be.”

“No, no, not at all.”

“Tell me what passed through your mind as I spoke.”

“I thought, ‘Right on.’ I like your speaking like this. I like your sharing your thoughts.”

“Well, here’s another one that just came up, an old memory of a case presentation at a seminar when I was a student, ages ago. The patient was a man who had a blissful honeymoon on some tropical island, one of the great times of his life. But the marriage deteriorated rapidly during the next year, and they divorced. He learned at some point from his wife that, throughout their time together, including their honeymoon, she’d been obsessed with another man. His reaction was very similar to yours. He realized that their idyllic relationship on the tropical island wasn’t a shared experience, that he, too, was playing a solo. I don’t recall much more, but I do recall that he, like you, sensed that reality was fractured.”

“Reality fractured . . . that speaks to me. It’s even there in my dreams. Last night I had some powerful dreams but can only recall a bit. I was inside of a dolls’ house and touched the curtains and windows and felt how they were paper and cellophane. It felt flimsy, and then I heard loud footsteps and was afraid that someone would stamp on the house.”

“Charles, let me check in again about our reality right now. I give you notice: I’m going to keep doing this. How are you and I doing now?”

“Better than anywhere else, I guess. I mean we’re more honest. But still there are some gaps. No, not some gaps—there are big gaps. We’re not really sharing reality.”

“Well, let’s keep on trying to narrow the gaps. What questions do you have for me?”

“Hmm. You’ve never asked that before. Well, many questions. How do you see me? What’s it like to be in the room with me right now? How hard is this hour for you?”

“Fair questions. I’ll just let my thoughts run and not try to be systematic. I’m moved by what you’re going through. I’m 100 percent in this room. I like you, and I respect you—I think you know that, or I hope you do. And I have a strong desire to help you. I think of how you’ve been haunted by your father’s death, how it’s left its mark on your whole life. And I think of how awful it’s been to have found something precious in your relationship with James Perry and then to have that wrenched away from you so suddenly. I imagine, also, that the loss of your father and of James looms large in your feelings toward me. Let’s see what else comes to mind. I can tell you that when I meet with you, I face two different feelings that sometimes get in the way of one another. On the one hand, I want to be like a father to you, but I also want to help you get past the need for a father.”

Charles nodded as I spoke, looked down, and remained silent. I asked, “And now, Charles, how real are we being?”

“I’ve misspoken. The truth is that the major problem isn’t you. It’s me. There’s too much I’ve been withholding . . . too much I’ve been unwilling to say.”

“For fear of driving me away?”

Charles shook his head. “Partly.”

I was certain now I knew what it was: it was my age. I’d been through this with other patients. “For fear of giving me pain,” I said.

He nodded.

“Trust me: it’s my job to take care of my feelings. I’ll hang in there with you. Try to make a start.”

Charles loosened his necktie and unbuttoned his top button. “Well, here’s one of last night’s dreams. I was talking to you in your office, only it looked like a woodshop—I noticed a stack of wood and a large table saw, a plane, and a sander. Then suddenly you shrieked, grabbed your chest, and slumped forward. I jumped up to help you. I called 911 and held you until they came, and then I helped them put you on a stretcher. There was more, but that’s all I can remember.”

“Hunches about that dream?”

“Well, it’s transparent. I’m very conscious of your age and worried about your dying. The woodshop element is obvious, too. In the dream I’ve blended you with Mr. Reilly, my woodshop teacher in junior high school. He was very old, a bit of a father figure to me. In fact, we all called him Pop Riley. Even after I graduated I used to visit him.”

“And feelings in the dream?”

“It’s vague, but I recall panic and also a lot of pride in my helping you.”

“It’s good you’re bringing this up. Can you speak of other dreams that you’ve avoided telling me?”

“Uh, well. It’s uncomfortable, but there was one a week or 10 days ago that stuck in my mind. In the dream we were meeting like we are now in these chairs, but there were no walls, and I couldn’t tell if we were inside or outside. You were grim-faced, and you leaned toward me and told me you had only six months to live. And then . . . this is really weird . . . I tried to strike a bargain with you: I would teach you how to die, and you would teach me how to be a therapist. I don’t remember much else except that we were both crying a lot.”

“The first part is clear—of course you’re aware of my age and worried about how long I’ll live. But what about the second part, wanting to be a therapist?”

“I don’t know what to make of that. I’ve never thought I could be a therapist. It would be beyond me. I don’t think I could deal with facing strong feelings all the time, and I do know I admire you a great deal. You’ve been kind, very kind, to me and always know how to point me in just the right direction.” Charles leaned over to take a Kleenex and wipe his brow. “This is very difficult for me. You’ve given me so much, and here I sit inflicting pain by telling you these dreadful dreams about you. This is not right.”

“Your job here is to share your thoughts with me, and you’re doing it well. Of course my age concerns you. We both know that at my age, at 81, I’m approaching the end of my life. You’re now grieving for James and also for your father, and it’s only natural that you’re worried about losing me as well. Eighty-one is old, shockingly old. I’m shocked myself when I think about it. I don’t feel old, and over and over I wonder how I got to be 81. I always used to be the youngest kid—in my classes, on my summer camp baseball team, on the tennis team—and now suddenly I’m the oldest person anywhere I go—restaurants, movies, professional conferences. I can’t get used to it.”

I took a deep breath. We sat quietly for a few moments. “Before we go further, I want to stop for another check, Charles. How are we doing now? How about the size of the gap?”

“The gap has narrowed quite a lot. But this is really hard. This isn’t normal conversation. You don’t usually say to someone, ‘I’m worried about your dying.’ This has got to be painful for you, and right now you’re one of the last people in the world I want to hurt.”

“But this is an unusual place. Here, we have, or we should have, no taboos against honesty. And keep in mind you’re not bringing up anything I haven’t thought about a great deal. A central part of the ethos of this field is keeping your eyes open to everything.”

Charles nodded. Another brief silence passed between us.

“We’re having far more silences today than ever before,” I ventured.

Charles nodded again. “I’m really all here and totally with you. It’s just that this discussion is taking my breath away.”

“There’s something else important I want to tell you. Believe it or not, looking at the end of life has some positive effects. I want to tell you of an odd experience I had a few days ago. It was about six o’clock, and I saw my wife at the end of our driveway reaching into our mailbox. I walked toward her. She turned her head and smiled. Suddenly and inexplicably, my mind shifted the scene, and for just a few moments I imagined being in a dark room watching a flickering home movie of scenes from my life. I felt much like the protagonist in Krapp’s Last Tape. You know that Samuel Beckett play?”

“No, but I’ve heard of it.”

“It’s a monologue given by an old man on his birthday as he listens to tape recordings he has made on past birthdays. So, somewhat like Krapp, I imagined a film of old scenes of my life. And there I saw my dead wife turning toward me with a large smile, beckoning to me. As I watched her, I was flooded with poignancy and unimaginable grief. Then suddenly it all vanished, and I snapped back to the present, and there she was, alive, radiant, in the flesh, flashing her beautiful September smile. A warm flush of joy washed over me. I felt grateful that she and I were still alive, and I rushed to embrace her and to begin our evening walk.”

I couldn’t describe that experience without tears welling up, and I reached for a Kleenex. Charles also took a Kleenex to dab his eyes, “So you’re saying, ‘Count your blessings.’”

“Yes, exactly. I’m saying that anticipating endings may encourage us to grasp the present with greater vitality.”

Charles and I both glanced at the clock. We had run over a few minutes. He slowly gathered his things. “I’m wiped out,” he whispered. “You’ve got to be tired too.”

I stood up straight, shoulders squared. “Not at all. Actually, a deep and true session like this one enlivens me. You worked hard today, Charles. We worked hard together.”

I opened the office door for him, and, as always, we shook hands as he left. I closed the door and then suddenly slapped myself on the forehead and said, “No, I can’t do this. I can’t end the session this way.” So I opened the door, called him back, and said, “Charles, I just slipped back into an old mode and did exactly what I don’t want to do. The truth is I am tired from that hard deep work, a bit wiped out in fact, and I’m grateful I have no one else on my schedule today.” I looked at him and waited. I didn’t know what to expect.

“Oh Irv, I knew that. I know you better than you think I do. I know when you’re just trying to be therapeutic.”

Excerpted from Creatures of a Day: And Other Tales of Psychotherapy by Irvin D. Yalom. Available from Basic Books, a member of The Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2015.

Illustration © Illustration Source / Alan E. Cober

Irvin Yalom

Irvin Yalom, PhD, is an emeritus professor of psychiatry at Stanford University and the author many books, including Becoming Myself: A Psychiatrist’s Memoir.