Every September, my family’s world would transform for two weeks as we’d escape Sacramento for Inverness, California. We’d leave behind our full schedules and the concrete jungle we called home for pine-blanketed paths and the gentle sound of water lapping at high tide. We’d stayed in a house my grandparents had built, on a cliff overlooking Tomales Bay. It’s the place where we felt most together. Late summers there meant a respite from the sticky Sacramento sun and freedom for the kids to wander safely, unattended by adults. Evenings meant oyster barbecues, the kids tinkering nearby with tiny woodblock villages and miniature pewter animals, and stories read aloud in front of the hearth. Without internet or phone, we unplugged and thrived.

When the kids got older, we’d play cards while the sky turned dark and the moon came into view. All five of us would circle around a huge, low midcentury table while we sat on a rug my grandmother had braided, made from old Pendleton work shirts. When the full moon splashed a golden path on the water, we’d follow the same family ritual we performed every year, and make our way down to the beach.

In 2018, the full moon night had a friendly familiarity, but this time was different. It was the year we said goodbye, the year we said our last thank-yous to the house, to my late grandparents’ spirits, who still puttered around the house they’d built, and to our family tradition of coming here. The 25-year trust in which the house had been held had expired, and we’d made the difficult decision not to participate in the new ownership plan. It was also the last time before my husband, Greg, and I moved our lives away from our adult kids. We’d made the bold choice to quit our suburban lives and buy a farm on an island in the Pacific Northwest. It was the last time we’d live together as a family in the same city. I’d worked like crazy for decades to cultivate this togetherness. I’d wanted to create a glue between us, a strong sense of connection: my kids to me, to each other, and to Greg.

Looking back, it feels obvious where this determination came from. As a teenager, I grew up taking notes, and I made a vow: I’m going to make a family that looks nothing like this, I told myself. My kids won’t have a single mom, unsupported, who has no emotional space after a long day of work. There won’t be fighting and long-held resentments by siblings who live with scarcity and conflict.

It was a cool and clear evening the last night Greg and I walked with the kids, single file, down the forest path to the beach. The canoe waited under the full moon. The bay was a silky, chromatic black. There was no need for us to talk. Ours was a ritual that didn’t need narration. Silently, we found our places in the boat, and Greg pushed us off into the water. Silently, we paddled, the swirling water from the oars bucketing the reflection of the shimmering moon. We sat together, transfixed by the beauty of it all.

Just then, a seal poked its head through the water. Simultaneously, we each turned our head to look as our bodies rocked on the slow breath of the bay.

I could’ve broken the silence. After all, I’m usually the squealer when something special happens. “Hi, little seal,” I wanted to say. “Hi, you sweet little precious thing.” I could have said it. But I didn’t.

Instead, I stayed silent with the others and listened as the boat made its way through the water.

After circling around the cove for a bit, we returned to the dock, got out of the canoe, and lay on the sand together, staring up at the moon.

I turned to look at Greg, and he squeezed my hand. There’s a moment at the end of the movie The Theory of Everything where Stephen Hawking is admiring his kids playing together around a fountain, and looks up from his wheelchair to smile at their mother. “Look what we made,” he says. There on the sand, I mouthed those words. Over two decades of parenting, Greg and I have made those words our own and have said them to each other often. They’ve become emblematic of the feeling of witnessing a miracle. We both took a deep breath, and soaked it in.

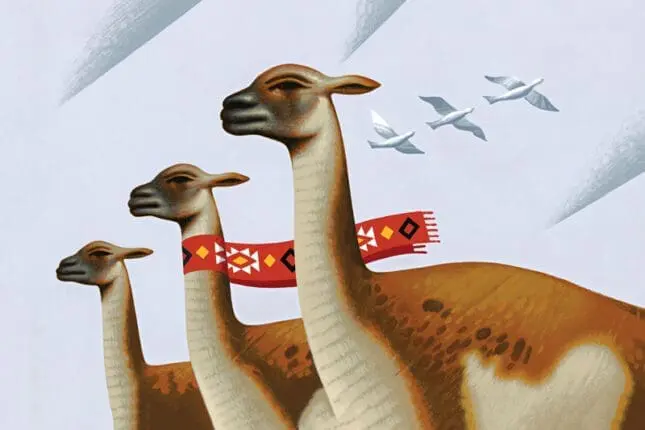

A year later, I’m in the barn at our island farm, 800 miles away from the kids. My life is vastly different now. We’ve started a new adventure. We raise guanacos, the wild Andean fine-fiber animal from which llamas descended. We care for these exotic beasts and use their rare fibers to create luxury products for spinners and knitters. For a lifelong knitter and fiber artist, this new endeavor is a dream come true, but I still wrestle with the missing, the longing for that feeling of floating on the bay in unison. I think about what we left behind, and the questions pour out. Did I break it? I wonder. Did we mess it all up by relocating and changing our lives? Have the miles apart stretched the glue too far, dissolving it into nothingness?

I feel the cool air of the barn on my skin, a refreshing respite from the hot sun, as I hurry to get the summer’s fiber dyeing finished. Soon enough, these blissful outdoor work days will be replaced by knitting and spinning indoors by the wood stove. Knowing it won’t be long until the chill and rain of the fall season arrive, I take a moment to soak in the simmering dye pots near our guanaco pen.

There’s a quiet peace about working so close to the guanacos. They, too, have decided to come in from the pasture and enjoy the cold cement. They’re perfectly spaced apart in a single-file, nose-to-tail line, bellies spread across the barn floor as they chew their cud.

I pull some of their precious fiber from the madder-root kettle. The shredded roots have been simmering for an hour, and their rich, red-orange dye has saturated the puffs of fiber. I want to run over to the guanacos and squeal, “Look at what you grew! Look at how it takes the deep orange! Look, look—it’s stunning! Aren’t you amazed?” Instead, I keep to myself. There’s no need to disturb their stillness. No need to startle them from their group ritual. No need to shatter my own sense of connection with these graceful, wild beasts.

As I move to the next kettle, I stop at the gate and peer in at them. I breathe in their sharp, grassy smell as they each turn their heads. It’s as if someone has pulled a string that causes them to swivel their long necks in unison. Their deep, black eyes settle on me. I’ve piqued their interest. I’m not a seal poking its head above the moonlit depths, but to them, I may be just as enthralling. I look back at each one as they stare, and wonder if I’ve broken the peace. I wonder whether the alpha female will haul herself up to leave and cause the others to do so as well. Instead, she stares serenely, and keeps chewing.

A few seconds later, she and the others turn their heads back to the pasture. The sun casts a golden glow on the drying grass. It’s another beautifully choreographed movement. I smile to myself as I notice that I, too, have turned my head in synchrony with the rest of them to watch the sunset.

This sense of connectedness is a dance that I’ve witnessed with other animals. When heads turn and hearts beat simultaneously, the herd mind resonates in all who participate. It happens when the swallows in Davis fly as one flock, swirling above the rice fields. Or when every seagull lifts off the sand excitedly, as if someone has thrown a switch and they simultaneously spring up, as from a jack-in-the-box. Or when sunning turtles on a log at the edge of a pond slide into the water, hitting the surface with such perfect timing that they create a single, big ripple, rather than a handful of small ones.

These natural phenomena mesmerize me. A herd, a swarm, a flock—they seem to have the ultimate sensory communication with one another. They don’t talk, they don’t warn, they don’t discuss—they just move, in union, as one organism. And it is magical.

In our guanaco herd, these moments are rarer than you’d think, but on this day, I remind myself to look out for them.

I guess it’s only natural that I begin to think of my kids again.

Last week, our oldest son, Mitch, broke up with the woman he’d once thought he was going to marry. We’ve talked on the phone many times, but underneath the words, I feel attuned to the pain in his heart.

My daughter, Ruth, was the maid of honor in her friend’s wedding last night. She showed me her hair and makeup on FaceTime. My heart beat faster as I thought of her toasting the bride and groom at the reception, 1,200 miles away.

My son Sam commutes to work, often two hours each way. Sometimes he calls me on his drive home. I feel his determination and work ethic in my body.

As much as I can feel them, I’m fairly certain they feel me. If we share a family mind, just like the herd mind, each time the feeling of missing them tugs at my heart, I like to imagine that they feel that pull too. The missing is a collective tug, asking us to turn our heads and, in sync, to reach across the distance for connection.

ILLUSTRATION BY ADAM NIKLEWICZ

Lisa Mitchell

Lisa Mitchell, MFT, ATR, writes and trains on the topic of creativity and therapy. She works with clients and therapists to partner with their creative process in her private practice in Sacramento, California, and blogs at Inner Canvas.