Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

Two months ago, Lucy, a single mom in her 30s, called me at her therapist’s urging. “My brother Sam molested me when he was 14 and I was seven,” she said. “I told my mother when I was a teenager, and it created a huge rift in the family. Sam’s no longer invited to holidays or family birthdays when I’m there, and my father stopped speaking to him. He has his own family now and has always said I misinterpreted our ‘closeness,’ which he’s told everyone was nothing more than harmless cuddling.” Lucy’s voice cracked on the word cuddling, and she paused.

“Is there more?” I asked. “Take your time.”

“Our middle brother, Marcus, who’s always believed Sam and lives next door to him, has two kids who are my kids’ ages. My mother’s remained in the middle, half believing that Sam was just an affectionate child, and even mentioning that children regularly experiment with their sexuality in families.

“The thing is, it’s been a decade since I’ve seen Sam and a few years since I’ve seen Marcus. I’m at the point now where I want our children to have a chance to get to know one another. I’m not interested in being close with Sam, but I do miss Marcus. I’d like everyone to be able to be in the same room again, but I’m still angry about what happened and worried my brothers will be cruel to me if they’re together.

“Tell me, is it possible or even advisable to move toward some kind of reunification? And if I did, how would it work?”

Therapists Doing Mediation

For as long as there’ve been human families, members of those families have been doing seemingly unforgivable things to one another. I specialize in family trauma and have seen how the effects of incest, violence, desertion, homophobic rejection, and emotional abuse result in rifts that last years, decades, often lifetimes. I’ve worked with families where accusations of abuse resulted in cutoffs by both the accuser and the accused. And more and more these days, I’m seeing families hamstrung by political differences so potent they’re creating a new class of estrangements.

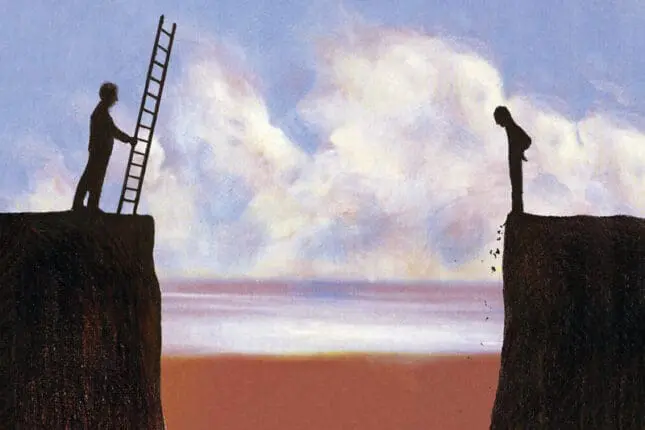

Trained to help people create the psychological room they need to heal, many therapists think the best intervention for clients with family trauma is to have less or even no contact with the people involved. But what do we do when clients like Lucy decide cutoffs aren’t working for them? Can we help them navigate reunions that’ll be fruitful and safe for them? And should we have a role in mediating this space?

Reaching Out

When our clients no longer feel imminently threatened by their abusive or offensive family members, the ongoing absence of family and its rituals can sometimes start to subsume the sense of freedom and safety that initially came with a cutoff. At some point, empty chairs at Thanksgiving or shrunken celebrations after a graduation can chill the warmth of a gathering that the separation was meant to preserve. Divides that once seemed insurmountable before grandparents got older and sickly, or nieces were born, might now carry more distress than they alleviate.

In these instances, I offer something I call Family Dialogue. More mediation than therapy, it’s a formal process that sets the terms of agreement for a new kind of relationship among estranged family members. It doesn’t delve into or attempt to heal all the pain that may exist. It doesn’t require apologies or forgiveness, or resolve past transgressions or allegations. In fact, it may never return a family to a state of loving openness. But if done right, it can establish agreed-upon rules for interactions that might create a new peace and allow for safe new family rituals and gatherings.

After journeying through the Family Dialogue process, people often end up adjusting the very notion of what family togetherness means. Rather than sharing every detail of life in weekly phone calls, maybe they can sit in the same room together for a meal once a month. Maybe they can agree to commit to fight-free holidays, even if that means no alcohol, and to staying in hotels instead of relatives’ houses. Or maybe they can let the kids sleep at their cousin’s place for the first time, even while a brother’s antique gun collection is on display in a locked cabinet, or a sister’s framed poster of Hillary Clinton hangs on the living room wall.

Designing a New Togetherness

When someone comes to me to initiate a Family Dialogue, we first decide if the process can address the future they want to create. We talk about past and current therapy experiences. If they’re in therapy now, I want to know if their therapist is on board with their being in conversation with estranged family members. Then, I ask to hear their goals in detail. Lucy told me she wanted to explore the possibility of a safe relationship with her brothers, and for her kids to know their cousins. She didn’t want the first time she saw her brothers again to be at a funeral for one of their parents. When it seemed that Family Dialogue might be a viable route for her, we moved to the next step: creating the invitation for the rest of the family.

I asked Lucy to write a letter to her brothers inviting them into this process. These letters typically begin with an acknowledgement. It might be something like, “I know we have huge differences,” or “I know we’ve been cut off as our parents age.” Then it’ll go on to say, “I’ve contacted a therapist and coach, who can help us see if we can create some type of relationship where we can have a respectful dialogue.”

In Lucy’s case, I coached her to write, “This isn’t about confrontation or changing each other’s minds, but simply having a conversation focused on possibilities in the future.”

Lucy had spoken to her parents before her call to me, and they were on board. But once we’d drafted the letter to her brothers, I had her end it by asking them to contact me on their own if they were willing to participate, so I could set up one-to-one conversations with each of them.

The letter worked, and Sam and I spoke first. I told him he was welcome to have his therapist join us on the Zoom call, but he showed up alone. His voice was shaky, and he tried to cover his distress by sitting tall in his chair. I immediately thanked him and explained my role: that I’d be working just as much for him as for Lucy. “I’m going to try to keep your perspective in mind as we go forward, so let’s try to talk about that a bit,” I said.

Sam settled back in his chair and looked out a nearby window. When he faced me again, he admitted that it had been easy to be close to Lucy, a sweet child in the midst of a family whose interactions were often contentious.

“I honestly have no idea where she got the idea that anything between us was inappropriate,” he said, “but I was shocked when that accusation started flying around. I think she took our closeness—I mean sometimes I’d nap on the couch with her—and blew it out of proportion. She was young, I guess. Maybe she saw all those news reports in the ’80s about child molestation and wanted to get Mom and Dad’s attention.” He paused. “She sure did that! Still, all these years of separation have weighed on me, and as angry as I’ve been about all this, I’d be open to finding a way for the family to be together again.”

I affirmed this intention of his, which he understood would involve creating a new reality with Lucy, and asked him to write a letter to her accepting the invitation to dialogue in person.

“Here’s what you do,” I said. “Find a way to express your gratitude that Lucy is open to this process, and explain what you value about her as a member of your family. What do you hope your relationship will look like going forward, understanding it’ll take time and effort on your part? Make it clear that you’re available to hear her and truly listen.” I asked to see the letter before he mailed it, so I could have the chance to edit anything that might be problematic.

Then I met with the other brother, Marcus, and apprised him of what was happening. Through it all, Lucy and I kept communicating. I explained to her that when we meet with estranged family members, whoever initiates the process is the first to speak. Since that would be her, I encouraged her to write down what she wanted to say.

She began by thanking Sam for meeting with her, and listing what she missed about having him in the family—which turned out to be his sense of humor, his ability to cook a proper meal, and his patience with his dad’s penchant for historical trivia. She wrote what she hoped to get out of the process: to traverse their complicated history without getting sucked into it and to see each other periodically as a family again.

The next few paragraphs revolved around her experience of her childhood and the impact it had on her. “You agreeing with my version of these events is no longer my priority,” she acknowledged. “What I’d like is for you to simply hear my experience.” She wrote this part shakily.

As she reached for a tissue, I reminded her the effort would be worth it. “When this dialogue takes place, you’ll be prepared for what you want to say and what you need them to hear. Think of this as improving the chances that this big step you’ve taken will be beneficial.”

“In the final section,” I told her, “describe what you want in the future and the boundaries you want to create with him. Finally, suggest a practical, baby-step plan to help increase the level of connection between you without eliciting anger or hurt.”

She wrote: “I don’t know that I’ll ever be comfortable with us being alone together again, so I’d rather we always meet with at least one other family member present. I’d like us to be able to be with the family at holidays, go on group outings, and not feel weird if we both randomly show up at Mom and Dad’s on the same day. I think we should do this in baby steps: maybe the first outing is a park with the kids and Mom and Dad for an hour, where we can easily walk away from time to time if it’s too much.”

Although Sam now understood from me that he’d primarily be listening to Lucy and validating her feelings, I had him prepare a similar series of prompts of his own to discuss with her. Sam had shared with me the difficulties he’d experienced as a child. He wasn’t a great student and didn’t have any particular talents or a big circle of friends. And when he came home from school, it was to a house that provided very little sense of sanctuary. As the eldest child of a short-tempered father, he often caught the brunt of the corporal punishment their dad meted out; both brothers were regularly hit, but Lucy, the only girl, was not.

“Okay,” I told him, “now describe all the behaviors you had back then that may have been the result of those difficulties or the limitations of how your parents handled family conflict. Be honest about which of the old behaviors might still be with you, and tell Lucy you’re conscious that these behaviors could trigger past reactions when you see each other again.”

He wrote, “I do believe I bullied you. I was angry back then, and I wanted to be close to you. So yes, I did do those cuddling things that might’ve felt bad to you. These days, I find I can still be controlling, and my wife complains about how I can be too much of a traditional ‘man of the house’—kind of like Dad in a way, I guess. But I never hit my kids.”

Before we hung up, he said to me, “You know, my anger with my parents always bearing down on me was intense. So outside of the terrible things she accused me of, I can see how that anger impacted her, and why she had some anger toward me.”

As we got to the end of this step, I asked Sam what he wanted from the process. It turned out his vision of a reunited family matched Lucy’s almost exactly: coordinating a visit to a local park where the kids could meet and the adults could fill each other in on their lives.

The Meeting Looms

With my mediation clients, I reiterate multiple times that family members must accept that their reality of what happened in the past need never be agreed on for a reunion to go forward. At first, Lucy found this tricky. Now that she was facing a process of many hours of togetherness, where we’d deal with any flare-ups and design together the ground rules for their future, the reality that she might never get that vindication hit hard.

“I’ve spent years praying for this,” she said, “but knowing he’s going to be here at my urging makes it feel like I’m the one responsible for all the damage, which has already been such a burden. I’m still afraid they all hate me, you know? Just as it felt like they did when I spoke up as a kid.

“Still, the mere fact that he’s expressed something emotional already is emotional for me,” she continued. “For so long I’ve thought of him as cold and cruel. I still believe he can be that way, but to see that he’s given this serious consideration and actually has a plan in mind is heartening.”

The first meeting in my office would be just Sam and Lucy and take about three hours. As emotional as this first meeting is for any client, I’m usually confident that I won’t lose family members at this point. It happens, but it’s rare.

I recently facilitated this process for a young woman who was trying to forge a relationship with her QAnon-believing grandmother. She’d flown to see me in Chicago from Tennessee and had stopped me in the parking lot before her first family meeting. She was second-guessing herself, and wondering whether the outcome would be worth the emotional strain.

“Why would I want a relationship where I’m unable to share my worldview? Isn’t that the whole point of family—that you have people who are close to you and support you?” she asked.

“I hear you,” I told her. “An essential grieving process is happening through all this, but it’s an opportunity to ask, ‘Why does family have to do that? Do you truly believe most family members really always see each other’s truths?’”

One of the key lessons of working in this realm is letting go of our vision of what our family of origin ought to have been; we all have to grieve it and let go. The process of growing up is about this letting go—letting go of dependency and an idealized picture of everyone being on the same page as a family unit.

Yes, we all wish for that idealized picture, but I’ve been doing this work for long enough to know it’s rarely reality. Even when childhoods are generally positive, kids move on to a life of their own, where they’ll do things differently. It’s perfectly natural for a family not to remain the center of deep intimacy. The act of launching into adulthood is a process of reimagining a family dynamic.

Together Again

Lucy and I were the first to arrive at my office. She chose the upholstered chair closest to me and didn’t move until her brother arrived, at which point I thanked them both for coming and reiterated what I’d explained on our initial phone calls.

“Much like a court mediator, my job here isn’t to provide a platform for everyone to tell their side of the family story, nor for ongoing expressions of hurt or anger,” I said. “I can acknowledge the strong feelings and grief that’ll be in the room, but the work today is to practice being together in a new place, one that can help you resist the pull of the pain you may carry and the need to have that seen.

“That said, there may be emotional flare-ups. I don’t want you to become too discouraged if this happens. Along with attending to those, we’ll practice interacting through niceties—some may even say superficialities—that will allow for a kind of reset of your earlier family dynamics and be necessary for keeping your peace intact over time. We’ll take breaks, and I’ll check in with each of you frequently to see how you’re doing.”

Over the course of the next hours, some boundaries we’d established were crossed, but it gave us the chance to catch and name the dynamics that were in play. At one point, Sam interrupted Lucy as she described her sense of defenselessness as a child, and I had to tell him to wait until she finished her thought.

When anger overwhelmed them, both Sam and Lucy took time out to call their individual therapists in an adjoining room, but they both eventually came back and recommitted to going forward. Often Sam listened carefully, repeating back to Lucy what he heard, asking clarifying questions, and validating her experience. But more than once he misheard her and responded with irritation to her description of their interactions as kids.

At these points, I had to say, “Wait. Now, Sam, you need to listen again.” When she repeated herself, Sam was mostly able to respond with more equanimity. “Did you feel heard this time, Lucy?” I’d ask. “Does he need to clarify anything?”

Toward the end of the day, when she described her experience of Sam’s abuse, he dropped his head in his hands and the room went still. Clearly, he was working hard to not be defensive.

Then it was Sam’s turn to speak. He told Lucy details of his childhood that she hadn’t known, including how Marcus, whom she’d always considered a good-natured goofball, had bullied him, both privately at home and in front of friends at school. He described how the combination of their dad’s abuse, Marcus’s betrayal, and the dog-eat-dog nature of school made him suicidal at one point.

He told her he’d begun therapy after the Family Dialogue had started because I’d suggested that he had his own history that he needed to sort through.

Lucy heard Sam and mirrored the listening and reflection process that he’d done with her. We then broke for the evening, after having made plans for self-care, which included checking in with partners and therapists, and trying to get a good night’s sleep.

We started the next morning by processing the day before, moving on to the agreements for the future, and creating a plan to present to the rest of the family. Their parents joined us in person to hear the plan, and Marcus was present on Zoom. Sam and Lucy asked the others not to inquire about the details of their one-on-one meeting but to try to respect the boundaries and plan they’d created together. To ensure their future success as a family, there was to be no cross gossiping.

They agreed the first meeting of Lucy and Sam’s families, with spouses and children in tow, would indeed occur in a park. The next meeting would be with grandparents. The intention would then be for the whole family to be together at a holiday in the near future.

Ultimately, all three siblings and their parents were able to sign off on a plan. As we left, Lucy’s parents hugged her. She and Sam parted by simultaneously putting their hands together and bowing, then laughed at their shared instinct to end this way.

A few months later, Lucy sent me pictures and a short video of the five of them and the four grandchildren squeezed together at Wrigley Field. The kids were in the middle, each with a hand in a giant container of popcorn, and Lucy and Sam were on opposite sides of the group. Lucy’s Cubs hat was on sideways, and Sam’s was backward. Their grins were a little smaller than everyone else’s, but no one seeing this family for the first time would question their authenticity.

Let us know what you think at letters@psychnetworker.org.

Mary Jo Barrett

Mary Jo Barrett, MSW, is the founder and director of Contextual Change and coauthor of Treating Complex Trauma: A Relational Blueprint for Collaboration and Change and The Systemic Treatment of Incest.