When I was coming out of grad school, in the 1970s, we had mostly generic approaches, with little in the way of specific methods for different problems, like marital conflicts, trauma, and OCD. Since then, I’ve been impressed with many of the advances we’ve made in the field. For example, in marital therapy, the Gottmans and Susan Johnson have given us much better protocols. Marsha Linehan’s work with borderline personality is a lot more helpful than what I was taught as a young therapist. People like Peter Levine and Bessel van der Kolk have shown us that treating trauma means going beyond simply having people repeat their terrible stories over and over.

That said, there are areas in which I think therapy may have gotten worse. The essence of therapy remains the relationship, and the greatest gift to a client with virtually any problem is a focused, curious, empathic listener. But right now, pressure to speed up therapy can undercut the sanctity of the therapeutic relationship. Like good cooking, I think good therapy takes time.

The kind of verbal, cognitive, come-and-sit-down-in-an-office approach is deeply unsuited to the poor and underserved populations that we’re increasingly ignoring, like refugees and immigrants. I’d like to see us develop more active, nonverbal group approaches, which could incorporate singing, dancing, massage, and trust-building exercises—the kind of work mental health workers did in South Africa and in Rwanda after the genocide.

Today, poor and working-class people have a hard time getting access to therapy, not only because of its expense, but because they don’t have enough time. If they’re holding down jobs, they can’t get in the hours therapists like to work. To reach a wider population, we need to broaden our approach and include more emphasis on public education in mental health. This can be everything from teaching yoga and mindfulness to holistic health and mental fitness.

The main area we’re failing right now is taking into account the impact of the larger culture on all of us. For example, I believe that awareness of global climate change is so horrifying that it induces a kind of a primal panic in us. We just shut down to the information because we simply can’t bear it. We can’t face the thought of the kind of grim future our grandchildren are likely to experience.

The daily bombardment of information overload is absolutely overwhelming to us. Humans aren’t built to absorb, process, and act on the amount of information we get every day. The result is that we’re warier and more compartmentalized than ever before. Therapy needs to acknowledge how increasingly fragmented we’re becoming and explore how to help people connect different parts of themselves, even if we never say a word about global climate change.

Evolution has designed us to respond to proximal information—how things smell, look, sound, and who and what we can touch. But all of a sudden with our global communication system, there’s no such thing as distal information—all information is proximal. That’s doing odd things to our arousal systems, our sleep system, our cognitive-appraisal systems.

Along the same lines, National Public Radio recently ran a fascinating report on Alex Bentley’s meta-analysis of the emotional content of printed words over the last century. They now have computers that can take all the words that appear in print and perform massive analyses of how the use of language has changed. What these analyses show is that, contrary to what we think in our psychologized culture, we aren’t using more emotional words now than we used in the early part of the century, and the words we actually use have changed. The roaring ’20s were the high point for words that expressed happiness; the World War II years were the era in which sadness was most frequently expressed. But the last part of the 20th century saw a dramatic increase in the use of words communicating fear. In 2008, the last year of the study, we used more fearful words than during any year in the last century.

In many ways, we’re treating people in therapy offices as if it were 1960. But it’s a really different time, and there are a lot of issues we’re not approaching because we don’t know how.

For me, as a therapist, the most interesting question to ask is still “What’s your emotional experience of the world?” And if you ask that question in the right way, the result can be a conversation that increases the moral imagination of both therapist and client, which I believe is one of the most important goals of therapy.

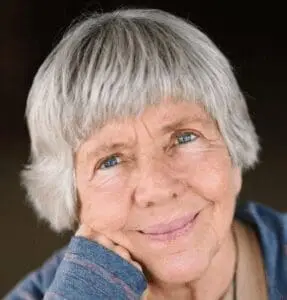

Mary Pipher

Mary Pipher, PhD, is a clinical psychologist, author, and climate activist. She’s a contributing writer for The New York Times and the author of 12 books, including Reviving Ophelia, Women Rowing North, and her latest, A Life in Light. Four of her books have been New York Times bestsellers. She’s received two American Psychological Association Presidential Citation awards, one of which she returned to protest psychologists’ involvement in enhanced interrogations at Guantanamo.