Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

A latte-sipping academic type walks into a gun show in rural Pennsylvania in search of so-called angry white men to interview about the fires that fuel their rage. “I’m your worst nightmare,” he tells prospective interviewees. “I’m a liberal New York Jewish sociologist, and I live in the bluest city in the bluest state in the country.” And with this line, at different gun show venues around the country, he signs up 40 men to provide glimpses of what makes them—and any potential emotional bombs inside them—tick.

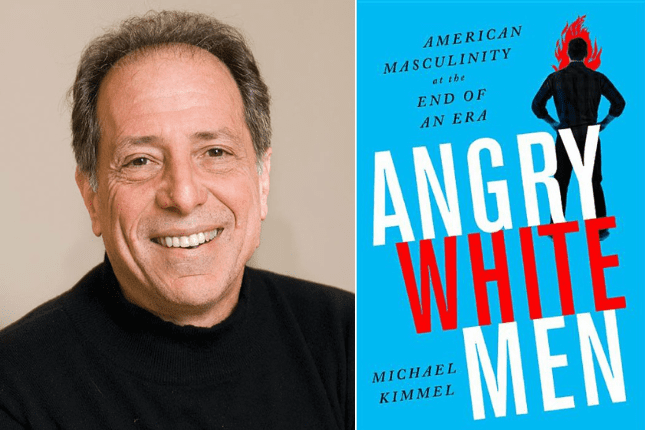

These glimpses are at the core of Angry White Men, the latest book by Michael Kimmel, professor of sociology and gender studies at Stony Brook University of New York. To Kimmel’s credit, he sets aside his own opinions and listens, for the most part without judgment, to a litany of complaints from his interviewees: tales of lost jobs, lost social and economic status, lost possibilities for happiness due to failed marriages and custody battles. Few, if any, of these disappointments or debacles are their fault, they insist: it’s America that has lost its way. Men are no longer on top. Women no longer know their place. Immigrant and ethnic groups are taking the jobs that should be theirs. These men aren’t just mad as hell, Kimmel reports: they feel justified in being so. Although, as Kimmel puts it, “the era of unquestioned and unchallenged male entitlement is over,” these men can’t or won’t accept it. This book helps us understand why and begins to provide a structure for dealing with such attitudes when encountered in clinical settings.

White male resentment has been written about before in any number of books and articles, but the focus of those works tends to be on either a particular manifestation of white rage (mass shootings, for instance, or white supremacist groups), or the effect of the economic shifts that have led to a massive loss of the types of industrial and manufacturing jobs that once provided solid foundations for a large cohort of working- and lower-class American men. Here, however, Kimmel takes the economic scenario as a given, a backdrop to the wounded, disrespected sense of manhood that he believes, given his expertise in gender studies, is the underlying source of anger in his interviewees. Moreover, rather than limit his study to a single tragic incident or a particular ideological group, he surveys a broad spectrum of organizations (from neo-Nazi cells to antifeminist men’s- and father’s-rights groups), a wide range of age groups, and the accumulated research into white grievance over the past decades. The result is a disturbing exploration of the exponential growth of right-wing talk shows, the persistence of hate groups, the terrifying increase in violence against women, and the rise in mass public shootings. Even scarier, the demographic of which these trends are emblematic, Kimmel believes, is more varied and widespread than stereotypes lead us to believe.

One reason for this spread is that our downwardly mobile era is leading to newfound affinities in disgruntlement between suburbanite professionals and rural working- and lower-class men. Another is the angry drumbeat of manipulative talk-show hosts and ultraconservative politicos. As Kimmel puts it, “Anger sells.” As to why so many people are buying, Kimmel’s thesis goes like this: angry white men feel adrift in a world no longer run exclusively, or even primarily, by men. They translate their failures at work and in love into disappointment, humiliation, and shame—a toxic mix that Kimmel calls aggrieved entitlement. They believe that their rightful place of power and respect has been usurped, in both the job market and the cultural milieu. This loss leaves them depressed and vulnerable—an attitude that experts in male psychology like Terrence Real say is common among men in general. Kimmel’s analysis would suggest the impact is even more acute on men whose egos are already in descent, further enabling the transformation of pain into rage. They displace their anger onto those who once upon a time were vulnerable but are now empowered: women (transformed into Rush Limbaugh’s feminazis) and nonwhites. Their other enemies are the combined forces of legislated equality and political correctness that they believe have taken away their jobs, their opportunities, and their chance to achieve the American dream. This narrative provides the rationalization for their anger. It allows them to cast themselves as the undeserving victims of a social order (i.e., government) that’s stripped them of the respect that should be theirs. The result is a whole lot of free-floating rage in search of outlets for expression. And the most dramatic example is mass shootings.

The psychological goal of mass killers, Kimmel believes, is to restore their manhood, to retaliate against those who have mistreated them, in a show of force that proves beyond doubt that they are the “real” men. Even if they lose their lives doing so, it will be as heroes, male heroes, who have evened the score. Indeed, postmortem profiles of adolescent and college-age school shooters often portray perpetrators who were bullied, marginalized, derided for not measuring up to the ideals glorified by cultural standards. As Kimmel writes, “One of the things that seems to have bound all the school shooters together in their murderous madness was their perception that their school was a jockocracy, a place where difference was not valued, a place where, in fact, it was punished.” The result, he posits, is a “synergistic interplay between shooter and school, between a shooter’s sense of masculinity, mental illness and his environment.” In other words, macho school cultures not only have the capacity to breed bullies: they can set the stage for those who have been bullied to turn on everyone, with guns blazing.

For the Ivy League–educated lawyer Roy Den Hollander, whom Kimmel profiles in his chapter on the men’s-rights movement, endless lawsuits are the ammunition of choice. Hollander has brought cases against bars that, he claims, discriminate against men by offering discounted drinks to women—but not men—on “ladies nights.” He’s sued Columbia University twice for discrimination because it offers a women’s—but not a men’s—studies program. He further contended that because feminism is a “modern-day religion” (elsewhere he called it a “man-hating ideology”), any state funding for such programs would be unconstitutional by reason of separation of church and state. Sure, he sounds like a nut, and he didn’t win any of these cases, but he’s one of a number of “male liberationists,” as Kimmel calls them, who seek to restore their status to the superior level held before the women’s liberation era. And there are also plenty of “angry white dads” organizations, whose members use endless rounds of vengeful custody litigation to intimidate, assert control, and show they’re still in charge.

Kimmel clearly doesn’t side with these groups, but he’s sympathetic to the pain of loss these men feel. The lesson for clinicians who try to help them and their families is that listening to and understanding that pain is essential. For many men, he writes, “women’s increased equality was experienced as an invasion of a previously pristine male turf.” Fathers and husbands facing the breakup of their families fear that “the amounts of love, care, and support (financial and emotional) they put into the family are unrecognized.” The sense of being dispossessed runs deep. Dismissing it as inconsequential can make it rise as anger.

While Kimmel also recommends therapeutic interventions and programs for men who abuse women, and encourages men to speak out against domestic violence to inspire and encourage others to change, as a sociologist, he’s more interested in social, rather than psychological, solutions. In that arena, however, he doesn’t offer much more than recommendations to engage in a national conversation on the issue and to encourage greater political engagement on social issues.

Ultimately, Angry White Men offers no overall solutions, but it does connect the dots that tie together different strains of male anger. Nonetheless, chapters can be repetitive (how many times do we need to read the phrase “mad as hell”?), and the writing cumbersome. Kimmel has an irritating habit of labeling examples or cases that date back two decades and more as “recent.” Similarly, one of his favorite cultural touchstones—the 1993 Michael Douglas movie Falling Down, about an out-of-work, divorced father who turns into a rage-filled gunman—is well worth watching as a classic portrait of an angry white male, but if you need a more timely frame of reference, all you have to do is read the news, or turn on a talk show, and you’ll know immediately what Kimmel is grappling with.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.