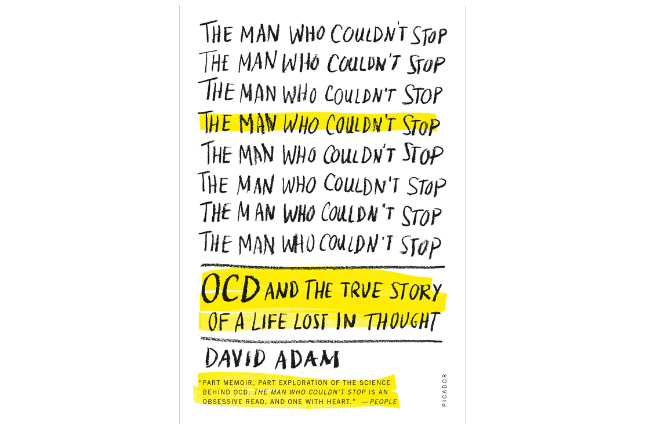

The Man Who Couldn’t Stop: OCD and the True Story of a Life Lost in Thought

by David Adam

Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 324 pages.

ISBN: 9781447238287

There was a reason I had to pause periodically and take a deep breath as I read science reporter David Adam’s personal account of his struggles with obsessive compulsive disorder, The Man Who Couldn’t Stop: OCD and the True Story of a Life Lost in Thought. It’s because I’ve also battled the unstoppable ruminations that characterize the disorder, and Adam’s spot-on descriptions of their imprisoning grip hit me with a shudder of recognition. Fortunately, ongoing treatment allows me to manage symptoms that would otherwise be overwhelming. But for Adam, as for me, finding that help proved painfully difficult—and not for want of trying or the efforts of well-intentioned therapists whose ministrations simply couldn’t break the symptoms’ stubborn hold.

That difficulty speaks to what Adam believes is a continuing disconnect between the reality of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and our understanding of it. OCD affects between two and three percent of the population, making it the fourth most common psychological disorder after depression, substance abuse, and anxiety. But even today, with so much more information available than in the past about so many other illnesses, OCD remains relatively elusive and misunderstood.

With that in mind, Adam has produced a comprehensive yet accessible exploration of the subject that can serve a double purpose. His first-person chronicle will hold out a potential lifeline for those who suffer from the disorder, while his in-depth review of research and treatment will provide an informative primer for professionals.

Adam’s struggles began in 1994, when he was 22 and became obsessed with the possibility that he could become infected with AIDS—despite being a healthy, straight male, married with two children; despite having never engaged in promiscuous sex or having had a blood transfusion; despite knowing in his rational mind that his fears were way over the top. And yet, as his book title says all too clearly, he couldn’t stop.

“I see HIV everywhere,” he confesses. “It lurks on toothbrushes and towels, taps and telephones. I wipe cups and bottles, hate sharing drinks, and cover every scrape and graze with multiple plasters. My compulsions can demand that after a scratch from a rusty nail or a piece of glass, I return to wrap it in absorbent paper and check for drops of contaminated blood that may be there. Dry skin between my toes can force me to walk on my heels through crowded locker rooms, in case of blood on the floor. . . . If I have a cut on my finger, or I notice that someone who I talk to has a bandage or a plaster over a wound, thoughts of the handshake and how to avoid it can start to crowd out everything else.”

As Adam discovered in his research, fear of infection or contamination in general, and AIDS in particular, is a common focus of obsessions, and is often accompanied with compulsive hand-washing or ritual-like cleaning. Other frequent OCD concerns include perfectionism and intolerance of uncertainty; an overestimation of threat that can morph into obsessions having to do with dirt, disease, and the safety of self and others; and the self-lacerating belief that merely thinking something bad is equivalent to actually doing or being bad.

Like so many sufferers of OCD, Adam would expend hours each day in a paralysis of rumination—in his case, going over and over again how he might accidently have been infected through, say, touching a surface in a locker room. Then, unable to convince himself he was infection free, he’d make repeated calls to AIDS hotlines for reassurance. But all to no avail. That’s one of the cruel features of OCD: reassurances don’t stick; only the obsessive worries do. Even if you can tamp down one worry for a moment (what a relief, Adam would think, the AIDS hotline confirms it’s almost impossible to get AIDS that way), it finds a way to pop right back up (wait a second, almost impossible doesn’t mean completely impossible). OCD thus distorts the thinking process, turning perspective inside out, magnifying infinitesimally small possibilities into likelihoods, reinterpreting risks so miniscule as to be ridiculous into probabilities writ large. Being unable to turn off the switch to these ceaseless thoughts gives way to an unbearable sense of oppressiveness and powerlessness.

So why not seek help, you ask. Even beyond the pain of being caught in the OCD maw, it’s acutely embarrassing for an otherwise rational, intelligent individual to admit to a nonstop onslaught of thoughts that sound even loonier when spoken out loud. And there’s another aspect that hadn’t previously occurred to me: the apprehension, especially when the ruminations focus on unfounded fears of causing harm to others, that the mental health professional may call the police. Indeed, Adam cites instances of that very scenario, and for that reason provides a script for how to broach discussions of the symptoms when talking to professionals. Because of such additional constraints and fears, Adam writes, many suffer from OCD in silence, making it “a secret disease and a silent epidemic.”

But even once someone with OCD makes an appointment, both diagnosis and treatment can be difficult because of the many faces the disorder can wear. OCD can present itself as compulsive repetitive behaviors or obsessive thoughts—or both. It can be accompanied by (or be the accompaniment to) anxiety or depression. Honest opinions may differ on the dividing line between a phobic fear of germs and an OCD-like compulsion to avoid touching anyone to evade an imagined contamination. Ditto for the ways in which OCD symptoms begin to meld into the unwanted flashbacks of post-traumatic stress disorder. And by the way, when does being conscientious about, say, fact-checking, ripen into the unstoppable need to recheck the same facts, again and again and again?

Even the editors of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual seem uncertain about how to classify OCD. DSM-IV bundled OCD into the chapter on anxiety disorders. DSM-5, however, devotes a separate chapter to what the editors call obsessive compulsive and related disorders. The spectrum ranges from OCD to body dysmorphic disorder, trichotillomania (hair-pulling disorder), hoarding disorder, and excoriation (skin-picking) disorder. There’s a rationale behind lumping these ailments together this way, as they all share a common symptomatology of obsessive thoughts or repetitive behaviors, or both. But whether deeper similarities that originate in the brain link them remains an intriguing question.

For Adam, the impetus to seek help came from his wife and children. He wanted to be present for them, not just for his obsessions. His experience, as well as his research, confirmed that traditional Freudian or psychodynamic therapies had little to no effect on the disorder. By contrast, cognitive behavioral therapy helped him untangle and tame his thoughts. That the therapy occurred in a small group allowed him to see he wasn’t alone in his struggles. But exposure therapy, though it works for some OCD clients, proved problematic for Adam, and I can understand why. You don’t have to have OCD to find it harrowing (or just plain icky) to be assigned, as an exercise, to smear your blood on your child’s face in order to build your capacity to endure stress. Adam just said no.

And then there was Zoloft, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) whose generic name is sertraline. “I call it a lifeline,” Adam writes, “a route back to the light from the darkest regions inside my head.” He takes a dose daily. So do I, and I’m in accord with him, as are about 60 percent of OCD patients for whom Zoloft or other SSRIs work. I also learned from experience—as did Adam—that going off Zoloft results in the quick return of the same debilitating ruminations that, when I started taking my prescription once more, dissipated and again became manageable. OCD can’t be cured: once you’ve got it, managing it is a lifelong discipline. As Adam puts it, having the disorder is “a bit like being a recovering alcoholic.”

These treatments represent great strides—a point Adam dramatizes by taking us through the sad and horrifying history of lobotomies and other questionable psychiatric surgeries of the past. But what about those for whom currently available remedies don’t succeed? “The good news is that scientists are constantly finding out more about the condition and the best way to diagnose and treat people with it,” Adam writes. Advances in neuroscience are shedding some light, and books like this do help broaden awareness. Disappointingly, Adam doesn’t go far in exploring what might be on the horizon.

Further, I found it surprising that Adam objects strenuously to how the OCD symptoms of the title character on the hit television series Monk (Tony Shalhoub) are often played for laughs. He doesn’t seem to recognize that Monk’s occasionally absurd preoccupations draw us to him with empathy, pathos, and understanding. Perhaps more than any other depiction of the disorder, the show has broadened public consciousness of the personal and professional toll of OCD. Like Adam’s book, Monk shows us that as wild as the compulsions and obsessions can seem, they’re no joke, but rather a mystery we’re still in the process of trying to penetrate.

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.