As a profession, we’ve become increasingly focused on our economic survival and seem to have turned a blind eye toward the broader social condition, voicing little about matters that aren’t central to our professional interest. For example, we’ve been mute around the recent race-related issues connected to Ferguson, Missouri, and Staten Island, New York. I don’t hear therapists becoming part of the cultural conversation about the strain in the relationship between police and communities of color, even though no professional group is more qualified to address relationship conflict than we are.

A tendency to ignore the wider social context is reflected in our increasing embrace of more manualized approaches to therapy, predicated on the notion that cultural differences don’t matter much, and you can apply techniques more or less uniformly across different treatment populations. While I don’t think that’s the intentional goal of manualized treatment, you might even see the increasing manualization as an indirect attack on diversity, squeezing out people who live on the margins of mainstream society.

Meanwhile, therapists on the ground in the barrios, in the hoods, and in the trenches often receive no recognition that what they do is “legitimate.” Many of these community-based approaches are changing disconnected lives, even though they may not match the current criteria of what constitutes “good” evidence-based psychotherapy. Plenty of people are working in places like the Bronx, North Philadelphia, and Oakland who are doing really creative work that wouldn’t be published in our professional journals.

In two important ways, good community work stands apart from the kind of approaches being encouraged in the field today. First, there aren’t rigid prescriptions governing who shows up for treatment, where the treatment takes place, or how many providers are engaged in the process. Therapists doing community work might invite participation from a client’s nonblood-related aunt, homeboys, or someone else who’s not a blood relative but might have an instrumental role in the person’s life. Second, when you’re dealing with multiproblem families, there isn’t the same pressure to focus on the saliency of a single presenting problem. You find yourself dealing with whatever the problem du jour happens to be.

Just last week, I supervised an inner-city community-based case in which an adolescent, Tasha, was the Identified Patient because of chronic truancy. She had an older sister who was using drugs and a stepfather who was allegedly verbally abusive toward her younger sister. The mother had a conflictual relationship with the stepfather, often accusing him of failing to live up to his responsibilities as “man of the house.” I believed all these factors were connected to why Tasha didn’t go to school: she was doing some caretaking for the family, both emotionally and physically, and school wasn’t a priority. In addition to Tasha, the therapist invited the stepfather, the older sister’s boyfriend, the mother, and the other siblings into the consulting room. Even Tasha’s best friend, Imani, was included in the process.

More and more, this approach to therapy is becoming less and less frequent in the field because of narrowly defined treatment protocols regarding who can be included in a therapeutic process, what can and can’t be a focal point, and the necessity to establish fidelity with a particular treatment model. In the community, therapists are much likelier to take a more inclusive, nontraditional approach to who’s included and to talk about issues like race, class, and life along the margins of society. In a narrow and superficial sense, these issues don’t seem relevant to a presenting problem like truancy, but they’re all crucial to understanding what’s really occurring in the life of a family.

Race remains an issue that most therapists are uncomfortable discussing. Currently, I’m supervising two therapists of color who are exceedingly reticent about raising issues of race within their training programs. When they do, they’re asked, “Why are you always talking about race?” In my own training, I remember a professor saying to me, “My job is to teach you the rudiments of family therapy. Your job is to learn them. Race and these other social issues that you continue to raise have no significance whatsoever. If you continue to focus on them as central issues in therapy, you’re going to find yourself without any clients.”

The experience of being discouraged from applying a wider perspective to what happens in therapy is commonplace. To this day, women in the field talk about the scars that they carry from raising issues about gender inequality 30 years ago. This still happens. I had a white colleague who said, within a few days of the Ferguson upheaval, “I don’t want to waste class time talking about issues that aren’t relevant to why we’re here.” While it may have been irrelevant to my colleague and the goals of the training program, it was a source of angst and deep concern among our students—and it was an issue that was continuously being raised in therapy by clients.

The field of psychotherapy as it’s currently practiced remains largely a white, upper-middle-class phenomenon. I don’t see a lot of students coming to training programs saying, “I want to work in the inner city.” But I emphasize to my students that there’s a way for us as professionals to be both socially conscious and market competitive, to find the balance between those things. There’s a way for us to earn a solid living and have a sense of social consciousness; for us as a community to speak up, speak out, and dare to have our voices about social matters be heard; for us to take bold positions in support of issues that are bigger than our professional self-interest.

Not everyone needs to carry picket signs, participate in protest marches, or forfeit opportunities for professional advancement, but we need everyone to commit to doing something. For instance, as clinicians, each of us could offer one hour of pro bono therapy weekly to those who are locked out and/or left behind in our current system of care. We could provide significantly discounted supervision and/or therapist self-care opportunities for those who work on the front lines in traumatized and disenfranchised communities. On a larger scale, we could choose to end our public silence and speak out against issues of injustice that threaten our shared humanity. After all, could there be anything more vital to our collective well-being and mental health?

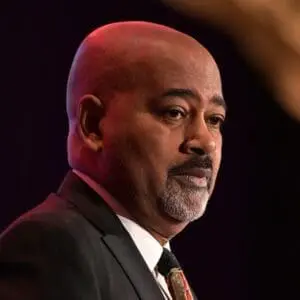

Kenneth V. Hardy

Kenneth V. Hardy, PhD, is President of the Eikenberg Academy for Social Justice and Clinical and Organizational Consultant for the Eikenberg Institute for Relationships in NYC, as well as a former Professor of Family Therapy at both Syracuse University, NY, and Drexel University, PA. He’s also the author of Racial Trauma: Clinical Strategies and Techniques for Healing Invisible Wounds, and The Enduring, Invisible, and Ubiquitous Centrality of Whiteness, and editor of On Becoming a Racially Sensitive Therapist: Race and Clinical Practice.