The first time a client tells me about a part of them that’s angry, I don’t jump to interpret or intervene. I get curious. As an Internal Family Systems (IFS) therapist, I want to know what that part of them is trying to do for them.

Take Maya, a client who came to therapy exhausted by an internal war: one part of her would flare up in anger at her partner during minor conflicts, while another part quickly stepped in to shut down the anger, criticize it, or rationalize it away. She described the angry part as overwhelming and “kind of scary,” and the rational part as the “voice of reason.” When I asked what she imagined might happen if the angry part wasn’t managed so quickly, she paused. “I’d be out of control,” she said. “People would leave me.”

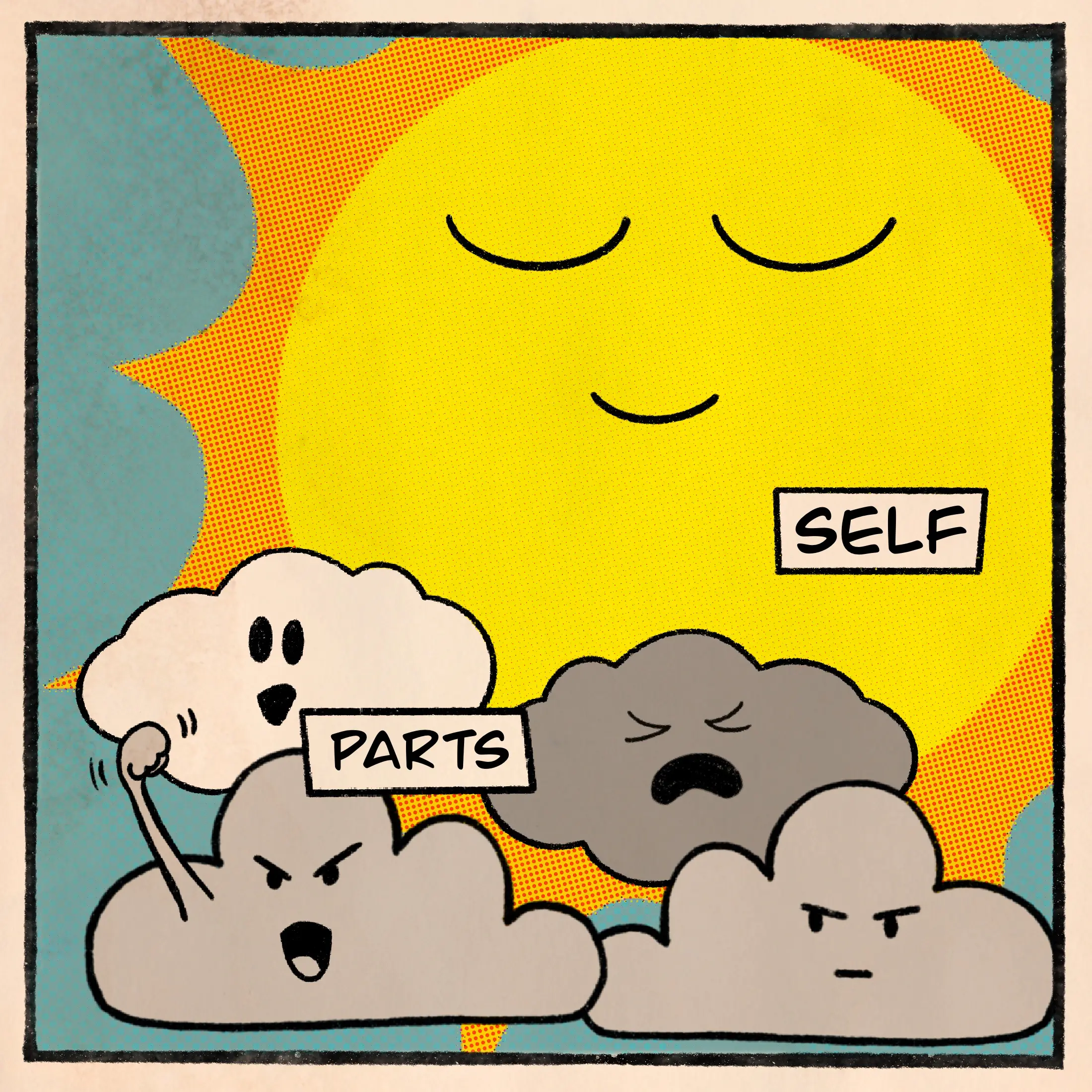

In my work, I use IFS as a framework to help clients understand how they get stuck in the protection strategies they’ve developed to navigate the complexities of life. I often begin with a simple analogy: most of us are familiar with the feeling of having conflicting voices in our heads. As we slow down and listen, we notice that different parts of us are advocating for different things. One may be seeking comfort or pleasure, the other protection, acceptance, or belonging.

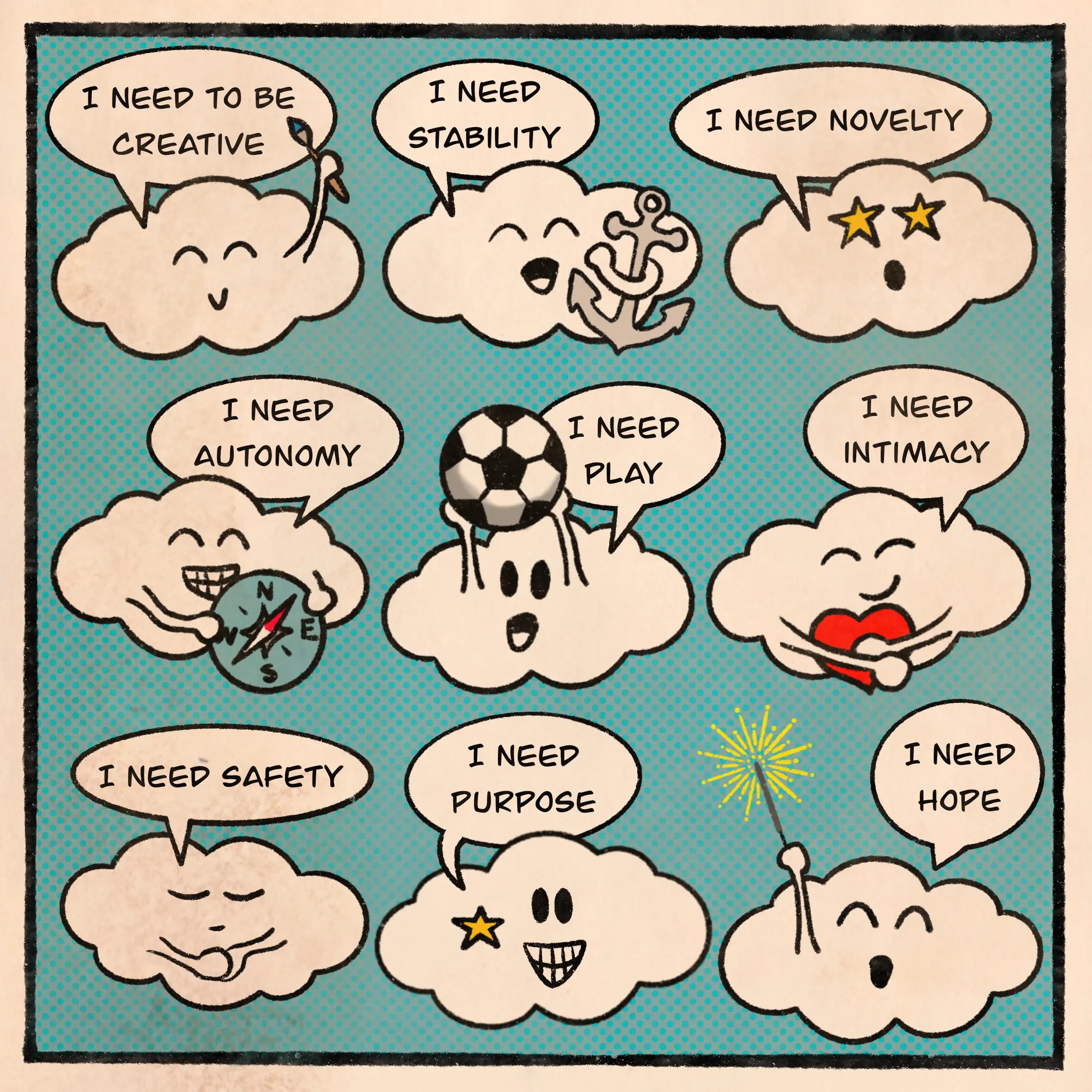

A common metaphor in the IFS community to describe this phenomenon is that our parts are like clouds, and our Self—the calm, compassionate essence at our core—is like the sun. Sometimes the clouds cover the sun, but that doesn’t mean the sun is gone. It’s just obscured. We don’t need to push the clouds away. We just need to understand them.

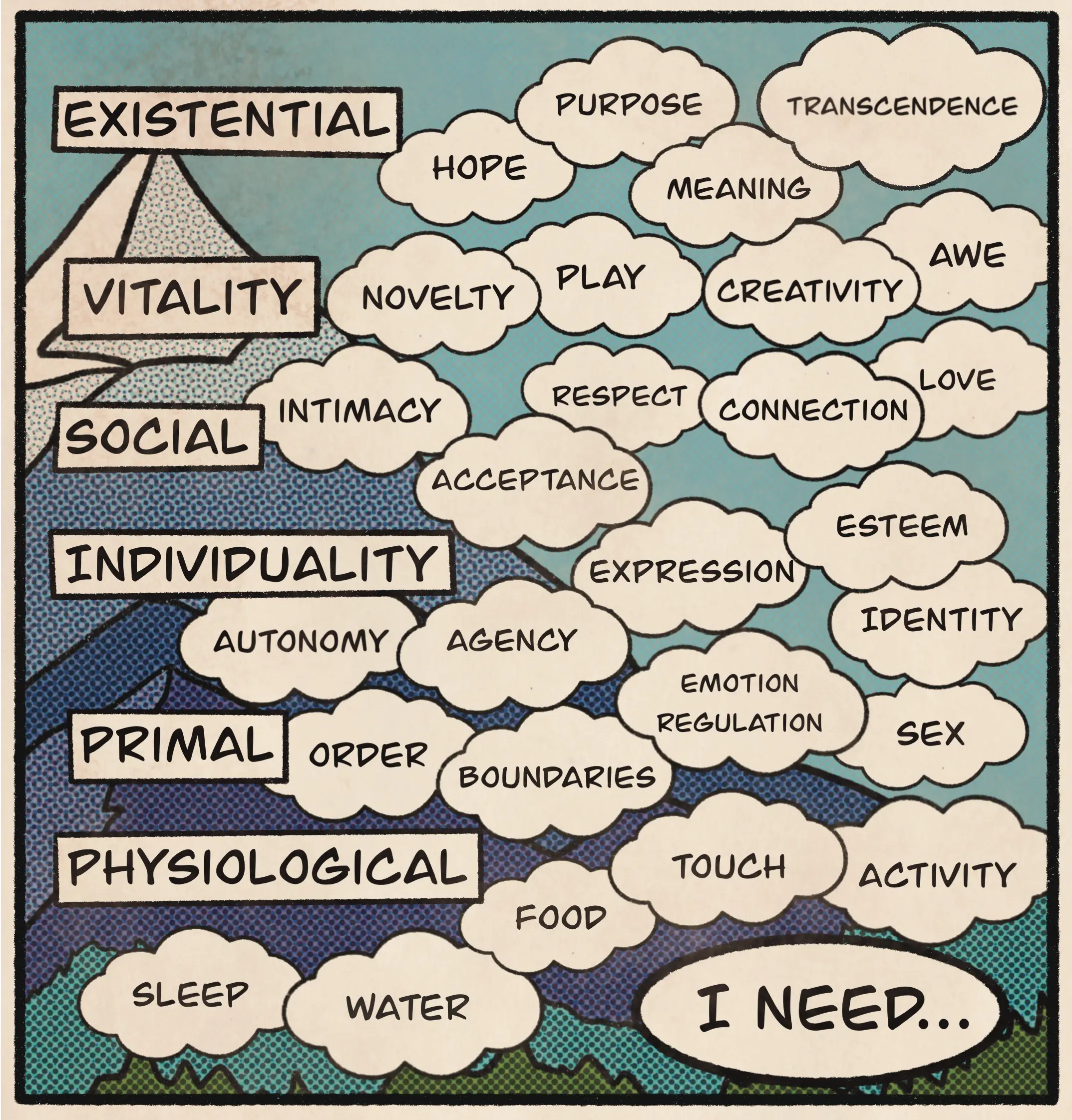

When a part gets activated, I invite clients to get curious about what need that part might be trying to meet. Are they reaching for safety? Autonomy? Connection? To be understood? For most of us this is a novel approach, not to just shut down any “unacceptable” feelings or emotions, but to earnestly look at the underlying reason with curiosity. I’ve found that IFS lends itself to a rich internal visual world full of metaphors and archetypes. Presenting clients with ways to visualize these internal dynamics has been a huge support for clients to move beyond self-judgment and into curiosity and understanding. One visual metaphor I developed around our needs is a reimagining of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. It is a collection of parts, depicted as clouds, presenting a collection of our universal human needs, as they swirl around a pyramid-shaped mountain.

For Maya, the angry part had long been dismissed or pushed away, but when we got curious, she began to visualize it—a young, sword-wielding 10-year-old cloud, fiercely protecting her from shame and self-doubt. He wasn’t angry for no reason; he was trying to keep her from collapsing into a sense of worthlessness. “It’s like he’s been working really hard for a long time,” she said. When I invited her to show him her adult self and let him know he wasn’t alone anymore, her whole posture softened. “He’s dancing around,” she smiled. “He likes being recognized.”

This wasn’t about “fixing” the part. It was about witnessing it, giving it space to reveal its purpose, and understanding that the behavior—however chaotic—was rooted in a core need to feel worthy and safe.

Sometimes I’ll say to clients, “Your parts are the embodiment of your needs.” Just as hunger leads to eating, internal discomfort drives parts to act. Some parts may seek relief through perfectionism, people-pleasing, or hyper-independence. Others may rebel, shut down, dissociate, or self-soothe in ways that don’t serve us. But underneath every strategy is a need trying to get met.

Another client, Amy, came in with a deep fear of abandonment. In romantic relationships, this fear would ignite what she once called her “rageful” part. But as we explored together, she realized it wasn’t rage—it was terror. This part would explode when she sensed her partner’s attention drifting to someone else, leaving her flooded, dissociated, and ashamed. “It’s not about jealousy,” she said. “It’s like I become a baby who’s terrified she’s going to lose everything.”

When I asked her what the part needed, she paused. “Space,” she said. “I’ve never had space when that happens. I’m always shut down or judged.” As we followed her imagery, she found herself sitting in a dark room next to the part—now a baby—who didn’t want to be left alone. Eventually, the baby let her pick her up, and Amy carried her out into a sunny garden, where she placed her in a bed of flowers surrounded by spirit guides. “She likes looking at the world,” she said. “She doesn’t want to be alone anymore.”

Through this approach we are able to reframe even the most disruptive behaviors as adaptations. IFS gives us language and structure to explore these adaptations without pathologizing them. It’s not, “I am crazy” or “I have to fix this.” It’s “A part of me feels terrified,” or “A part of me thinks I need to do everything perfectly.” That shift alone can help clients unblend from the reaction and move toward understanding.

With another client, Jules, we mapped out a part that tried to do everything—overhaul her routine, fix her emotions, be productive every minute. She called it “the do-everything part,” which would kick in after periods of zoning out or emotional overwhelm. We noticed how one extreme behavior would trigger the other: hyperactivation followed by shutdown. “It’s like I swing from one extreme to the other,” she said. As we tracked it, she recognized one part trying to outrun discomfort and another trying to numb it. Both were strategies to manage overstimulation. Both were trying to meet the need for ease and control.

To help her see this visually, I shared an illustration that shows parts at opposite sides of a boat, leaning out over the rails, both struggling to keep it from capsizing. When the parts are stuck in extremes, the boat rocks wildly. When Self is present, the system finds more balance.

These images help clients feel what’s happening inside. The metaphors give shape to the ineffable. At some point, I share that I see our parts as the necessary strategies of our humanness—adaptive patterns designed to keep us safe, secure, and connected in a complex world. Meanwhile, the Self is not just a better part; it’s something more akin to our spiritual essence—our capacity to witness, to love, and to lead with wisdom. The dance between our parts and our Self is the dance between our survival strategies and our soul.

I’ve found that IFS becomes much more accessible—and even playful—when we translate psychological jargon into universal experiences of need and care. And when clients begin to see their behaviors as expressions of their unmet needs, they soften. They get curious. They stop asking, “What’s wrong with me?” and start asking, “What do I need?”

That’s where the healing begins.

J. Ashley T. Booth

J. Ashley T. Booth, LCSW, MS, is a psychotherapist, illustrator, and psychedelic therapy trainer. She is the author and illustrator of Quieting the Storm Within: An Illustrated Introduction to Your Parts through Internal Family Systems and Beyond. Contact: ifsandbeyond.com.