Enjoy the audio preview version of this article—perfect for listening on the go.

What if our therapeutic goals of improving self-esteem, developing a stable and coherent sense of self, and identifying and expressing genuine, authentic feelings all turn out to be symptoms of delusion? And what if the current mindfulness craze—if we take it seriously enough—changes who we think we are and what we’re trying to do in therapy?

Like atomic energy in the 1960s, mindfulness is lately being seen as the cure for everything. Depression, anxiety, alienation, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, financial difficulties—you name it and there’s a mindfulness-based remedy for it. And while it’s true that reducing stress and giving us respite from our incessant thoughts can make almost any condition feel better, serious engagement with mindfulness practice is likely to produce an unexpected, often unwanted effect: it can lead us, and our clients, away from our comfortable constructs and toward a radical reappraisal of who we are and what our life is all about, upending our psychotherapy practices in the process.

In the Buddhist traditions from which many contemporary mindfulness practices derive, mindfulness techniques evolved as tools for deconstructing our usual view of ourselves and the world, for waking up from conventional, socially reinforced fictions about who we are and how to find happiness. This awakening occurs to the degree that we no longer believe in the self. It involves realizing what’s called in Pali—the language in which the Buddha’s teachings were first recorded—anatta, or non-self.

The mindfulness practice that leads to recognizing anatta is deceptively simple. It begins with cultivating concentration—choosing an object of awareness, such as ambient sounds, the breath, or other body sensations, and returning attention to that object every time the mind wanders from it. Once some concentration is established, we open the field of awareness to attend to whatever predominates in consciousness. Throughout the process, we try to accept whatever arises, whether pleasant or unpleasant.

If we engage in this simple practice long enough, we discover that our sense of being a separate, coherent, enduring self is actually a delusion maintained by our constant inner chatter, which generally features “me” at its center. From mundane decisions (“I think I’ll get the salmon with wilted spinach tonight”) to existential fears (“What’ll I do if the lump is malignant?”), this chatter fills our waking hours. Listening to it all day long, we come to believe that the hero of this drama must exist.

But if we practice mindfulness long and often enough, this conventional sense of self can start to unravel. By repeatedly bringing our attention to sensory experience in the present moment, we see that what arises in consciousness is a kaleidoscope of sensations and images, regularly narrated by subvocal words, which themselves arise and pass. Attention goes from the sensations of breathing, to a sound, to an itch on the scalp, to an image of a client, to remembering an upsetting email. We never actually find the little homunculus, the heroic man or woman inside, the stable and coherent “I” so regularly mentioned in our passing thoughts. Rather, there’s just a continual flux of changing mental contents.

If we cultivate sufficient mindfulness, we may even see how we create our sense of self, and our understanding of the world around us, out of this flux. Seeing this in action can pull the rug out from under us in alarming—though potentially liberating—ways.

How We Construct Reality

Ancient Buddhists described the process by which we construct reality and our sense of self much as modern cognitive scientists do. It all begins with sense contact: the coming together of a sense organ (the eye or ear, for example) with an object of awareness. These sensations are then immediately organized into perceptions, conditioned by language, personal history, and culture.

The mind doesn’t stay at the level of perception for long, however. It immediately adds a hedonic or feeling tone to all experience (“I like this” or “I don’t like this”). And almost as soon as the feeling tone enters consciousness, intentions arise. We have an impulse to hold onto pleasant experiences and push away unpleasant ones. Over time, we develop habits of intention that we might call dispositions or conditioned responses—collections of habitual responses to our likes and dislikes. These dispositions become important elements in our identities (“I’m a liberal,” “I listen to classical music, “I hate jet skis,” “I’m into mindfulness,” and so forth).

Most of us don’t fully appreciate the degree to which what we think of as our personality and sense of self is actually a collection of these likes, dislikes, and intentions, solidified over time. We see the process most clearly in teenagers. They’re always busy defining themselves by the kind of music they enjoy, or whether they like academics, sports, or art. I remember seeing this vividly when college shopping with my twin daughters. After visiting yet another beautiful New England liberal-arts college, complete with Olympic-level athletic facilities, world-class curricular offerings, and a gourmet dining hall, I asked one of them for her impressions. She said, “It’s obviously a great school, but I don’t think I’ll apply.”

“Why not?” I asked naively.

“Did you see what the kids in the dining hall were wearing?” she replied.

“Clothes?” I offered. “Jeans and flip-flops like you, your sister, and all your friends wear?”

“Oh Dad,” she said, rolling her eyes. “Can’t you see that they’re all totally emo?!”

When I was in high school, we had three groups: jocks, nerds, and the kids on the penitentiary track. By my daughter’s day, the number of categories had burgeoned, and emo referred to kids who had a lot of angst and expressed it through poetry, drama, and art, but weren’t as nihilistic or suicidal as the goth kids. And apparently my daughter could determine, based on the particular jeans and flip-flops that the kids in the dining hall were wearing, that they were emo. She wasn’t, so this college was out.

We may imagine that as adults, and particularly as sophisticated psychotherapists, we’ve moved beyond this sort of primitive identity formation, but I’ve often tried an experiment with groups of clinicians that suggests otherwise. First I ask, “Who here listens to National Public Radio (NPR), at least occasionally?” Usually about two-thirds of the hands go up. Then I ask, “Of you who listen to NPR, how many of you drive, or aspire to drive, a Hummer?” No hands ever go up. How did I know? Clairvoyance? Clinical acumen? Nope. It’s because nobody who listens to NPR would ever want a Hummer. It just doesn’t fit “who they are.” So even though we don’t like to think of ourselves as creating an identity based on something as shallow as patterns of likes and dislikes, and habits of pursuing some things while pushing away others, this is precisely what we do.

What we see through mindfulness practice is that creating a sense of self is actually an impersonal process. As the neuroscientist Wolf Singer famously said, “The brain is like an orchestra without a conductor.” These impersonal processes—sensation, perception, feeling, intention—unfold moment after moment, relentlessly narrated by thoughts that themselves arise and pass.

Our sense of self has other dimensions, too. These turn out to be equally insubstantial. Most of us identify with the body as “me.” Outside the skin is the world; inside is me. But what happens when we eat an apple? At what point in the journey from your hand, to pulp in your mouth, to gastric mash, to sugar in your blood does the apple become “you”? And what about the cellulose, or fiber, aggregating and getting ready to enter a familiar white porcelain receptacle? Is that you? Is it still the apple? Or is it something else? (Most of us pick “something else” because we don’t like to think of feces as either “me” or “my food.”) Upon examination, our cherished division between “me” and the rest of the ecosystem in which we reside falls apart.

Most of our clients may never practice intensively enough to see clearly how their sense of self is constructed from these elements, but if we therapists can awaken to this reality, it can help us take ourselves less seriously, be less preoccupied with our personal pleasure and pain, and provide a therapeutic attitude that can help our clients do the same.

Non-self in Psychotherapy

Seeing how our sense of self is constructed isn’t just a topic for abstract philosophy. In Buddhist psychology, awakening to anatta, or non-self, is central to psychological freedom. And even glimpsing anatta in our mindfulness practice can have profound implications for how we practice psychotherapy.

What might treatment look like if there’s no coherent self to be found or developed? What if trying to establish a coherent sense of self is itself a central source of suffering, as Buddhist teachings suggest? What does this mean about developing self-esteem? Identity? Authenticity?

Some changes are simple. Instead of asking in therapy, “How did that make you feel?” we could inquire, “What’s happening right now?” Instead of helping our client identify his or her authentic self, we could highlight how everything changes moment by moment, including who the client thinks he or she is.

A friend of mine who’s both a minister and a clinical psychologist is fond of pointing out that polytheism, not monotheism, is the norm historically. The ancient Greeks and Romans had their pantheons of gods, each one representing a different aspect of human personality. Many Christians revere various saints, each of which may represent a different virtue or aspect of our nature. Tibetan Buddhists have a pantheon of bodhisattvas that play similar roles, and Hindus have thousands of gods, each with a different personality. Animistic cultures worldwide have spirits representing every imaginable human impulse or tendency.

Psychotherapeutic traditions mirror this to different degrees, often describing the self as made of different parts. Freud had his ego, id, and superego; Jung his animus, anima, shadow, and persona; modern psychoanalysts identify different self-states. Roberto Assagioli’s psychosynthesis described multiple subpersonalities, and more recently, Richard Schwartz developed the Internal Family Systems model, which helps clients identify a pantheon of internal parts and uses insights from systems treatments to help these parts get along better with one another.

While seeing oneself as made up of many parts, each of which predominates at times, may feel a bit more like having a self than seeing oneself as a fluid organic process, all these models point to something we see in mindfulness practice: if I objectively observe consciousness moment by moment, I discover a continually changing landscape. The Ron Siegel who appears to be a balanced, knowledgeable professional leading a workshop or treating a client is quite different from the Ron in an argument with his wife or daughter. Shockingly different, in fact. Angry Ron, frightened Ron, greedy Ron, generous Ron, and loving Ron may all share a common social security number, driver’s license, and physical appearance, but that’s where the coherence ends. Without the glue of a narrative about “me,” these selves are different organisms.

Mindfulness practice can dissolve this glue, with profound implications for psychotherapy. For example, my client Gretchen recently found herself stuck in a depressive funk. She’d lost hope again that she’d ever have a meaningful job or relationship and was ruminating about her inadequacies. Highlighting the fluidity of her sense of self helped her gain perspective.

“How are the thoughts and feelings arising now different from a few weeks ago after your promising date with the architect?” I asked.

“I was just fooling myself back then,” she answered. “He seemed like a great guy and I got carried away, imagining a great future. Now I see things more clearly.”

“Do you remember that you were struck back then at how negatively you see yourself and the world when you’re down? How Depressed Gretchen is so different from Okay Gretchen? It sounds like Depressed Gretchen is back,” I said.

“I guess so,” she replied. “It feels like she’ll be around forever. But that’ll probably change, too.”

Psychological treatments strive to move clients toward health. But this health is determined in large measure by cultural norms. Anthropologists have long noted that Western cultures tend to be more individualistic than Eastern and nonindustrialized societies. So it’s no accident that Western models of health include being aware of boundaries and one’s own individual needs, and having a clear identity and sense of self. In fact, before managed care, these were seen as treatment goals. (Now, a typical goal is to decrease self-deprecating thoughts by 27 percent by next Tuesday.)

This is in marked contrast to cultures in which identification with nature, family, the tribe, or even ancestral lineages is emphasized and honored. As South African social-rights activist Desmond Tutu has said, in many African cultures, if someone asks, “How are you?” the answer is either “We’re fine” or “We’re having trouble.” Individual well-being outside of the group’s experience is inconceivable.

One effect of mindfulness practice is to dismantle our modern Western sense of autonomy, yielding several positive—albeit initially disturbing—consequences. If I’m identified with certain traits or dispositions as “me,” I’m going to have trouble when other aspects of my humanity appear. For example, if I like to think of myself as generous, hardworking, and intelligent, I’m going to have difficulty when my greedy, lazy, dumb sides show up. Indeed, this is what Jung called our shadow—split-off elements of the personality that aren’t acknowledged as part of our conscious identity. As long as I’m denying or resisting these elements and seeing them as “not me,” I’ll be in constant tension, inclined to project them onto others and be judgmental when I see them there.

My client Eddie, for instance, had been an angry kid, always in trouble for being too rambunctious. His parents regularly compared him unfavorably to his sister, a model of comportment. Eddie eventually learned not just to hold it together, but to be an unusually well-behaved, nice guy. His girlfriend was positively smitten with his stability and kindness. Although he tried hard never to get mad, his anger still cropped up at times, triggered by little things that he thought shouldn’t bother him, like a competitive colleague at work or a rude store clerk.

In therapy, Eddie worked on simply being with the anger as a moment-to-moment bodily arousal, separate from the thought I shouldn’t be this way. Gradually, he was able to see the anger less as an indication of badness and more as a part of our shared mammalian nature. He came to see that being nice wasn’t really who he was either: these different aspects of human nature were just part of the fluid organism called Eddie.

So one result of embracing anatta is recognizing that it’s all part of a passing show. We can accept every aspect of this organism, rather than identifying with some elements as “me” while rejecting others. As a Zen patriarch put it, “The boundary of what we can accept in ourselves is the boundary of our freedom.” The alternative to accepting our varied states is dissociation, whether the mild form that we call having a clear identity and sense of self, or the stronger version, in which we completely split off unwanted contents—perhaps even into other identities—only to be haunted by them.

How far might this extend? To the inner murderer? The inner rapist? Here it’s important to recognize that we’re not talking about accepting all behavior, as some behaviors are unwise or destructive. But it is possible to accept a full range of impulses, choosing not to act on the harmful ones. Initially, this can be a hard sell in therapy, since clients often fear that acknowledging destructive impulses will lead to acting on them. But they can be encouraged to consider that we’re likelier to act unreflectively on impulses that we don’t know well, so the more we can allow our shadow sides into awareness without identifying with them, the less likely we are to enact them.

Another advantage to losing the glue of a coherent identity is that it enables us to connect more readily with others. To the extent that we can see both the saint and sinner in ourselves, we’re better able to accept others, warts and all. Our judgments about good and bad tend to lighten, and we can more readily feel compassion toward other people when they act in less-than-noble ways.

Eddie wasn’t just torturing himself by denying his aggression: it made him judge his younger brother harshly. He thought his brother was hopelessly immature because he got into battles with their parents. As Eddie became more comfortable with his own anger, he began to see that his brother actually had a point: their parents really could be annoying.

The Failure of Success

I had the privilege several years ago of traveling through African wildlife parks. Time and time again, our guides would point out scenes of a dominant male surrounded by a pack of healthy, fertile females. Somewhere nearby were other females, perhaps not at the peak of fertility, and the young kids. Off in the distance were adolescent males, honing their skills to compete for the dominant male position. This pattern repeated in a remarkable range of species. These hierarchies in the animal world have huge effects on the individuals concerned. As stress physiologists like Robert Sapolsky at Stanford point out, “It’s particularly bad for your health to be a low-ranking male in a primate troop.”

By helping us observe—rather than identify with—our thoughts, mindfulness practice reveals how often we’re concerned with our rank in our particular primate troop. Other species may stick to a few variables, like who’s stronger or more fertile-looking, but we compare ourselves to one another in a remarkable range of domains. For one person, it’s who’s smarter; for another, it’s who’s richer; for someone else, it’s who’s more popular. Then there’s who has the better body, the better-behaved child or spouse, the better clinical practice, the more developed sense of style, athletic ability, or social graces. The list goes on and on. Among meditators, this gets really ridiculous: Who’s less self-centered? Who makes fewer comparisons to others?

When we win in these comparisons, we feel good about ourselves—briefly. In our psychological models, we call this process healthy narcissism or self-esteem. The problem is, it’s impossible to come out on top consistently. Unless we live in Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegon, “where all the women are strong, all the men are good looking, and all the children are above average,” some of us are always going to land below the median.

Trying to feel good about ourselves by enhancing our self-esteem leads to all sorts of folly. As early as 1965, Caroline Preston and Stanley Harris studied drivers who’d had serious accidents, and they compared them with matched controls with good driving records. Ninety percent of both groups rated themselves as more skilled than other drivers, even though the drivers involved in accidents had considerably worse driving records than average. Later, in a 1976 survey by The College Board, 85 percent of students ranked themselves above the median in their ability to get along well with others, and 25 percent even rated themselves in the top 1 percent. Other research shows that most people think they’re better looking, nicer, more popular, logical, funny, wise, and intelligent than others. This extraordinarily robust tendency has even earned a name in social psychology: the better-than-average effect.

The problem with self-esteem is that in order to feel okay about ourselves, we need to puff ourselves up while putting others down. This leads to all sorts of prejudices, such as thinking that I or my group is better than you or your group. It also keeps us from looking honestly at our shortcomings, and thereby prevents us from addressing them.

Just think of accomplishments that once elevated your self-esteem: perhaps earning your professional degree, getting a job, buying a house. Did you wake up this morning feeling good about yourself because of these achievements? Most of us habituate pretty quickly to our new level and quickly return to feeling inadequate in one way or another.

My client David was an anxious, episodically dysthymic young man with clear goals. He’d read all the latest books about success and had enthusiastically crafted his strategic-objective scrapbook. It had pictures of a big suburban house, a luxury car, and a beautiful wife. He intended to acquire these in the next five years. I suspected that while he may indeed achieve his external goals, he’d soon recalibrate and be left feeling inadequate. So we began to explore in therapy how he came to believe that these achievements would bring him happiness and exactly what happens when he doesn’t feel he’s winning the game of life. It took a while, but he eventually connected with a series of traumatic humiliations, including being dominated by an older stepbrother and cheated on by a gorgeous college girlfriend. On top of this, he recalled his father’s oft-repeated disparaging names for the “losers” of the world.

As therapy unfolded, David finally got relief from his anxiety and dysthymia, not by fulfilling the imperatives of his scrapbook, but by seeing them as attempts to insulate himself from the pain of feeling inadequate and noticing the addictive quality of his narcissistic pursuits—how winning made him feel good for a few moments but soon left him needing more.

Indeed, despite its obvious limitations, most of us persist in trying to bolster our own—or our kids’—self-esteem through pursuing countless goals. But as Joseph Campbell famously put it, we often “climb the ladder of success only to discover that it’s leaning up against the wrong wall.” Mindfulness practice and the awareness of anatta vividly illustrate the folly of trying to improve or maintain self-esteem. We see repeatedly that what goes up must come down, and we notice that eventually we all succumb to illness and death, making the pursuit of self-esteem a losing proposition.

The alternative, which arises naturally out of the awareness of anatta, is self-compassion. Instead of trying to regain our competitive position after a fall, we acknowledge the painful feeling of disappointment and offer ourselves loving understanding. For example, if my daughter doesn’t make the soccer team, instead of reassuring her by saying, “But you’re better than other kids in math, and you’re a great ice-skater,” I might share with her, “I was disappointed when I wasn’t chosen for a part in the school play. I remember that it hurt, and I felt bad about myself when it happened.” In this way, I’m being with her in her suffering. Instead of pointing to a compensatory strength, we comfort others and ourselves with acceptance and a reminder of our common humanity—the awareness that we’re together in this life of winning and losing, joy and sorrow. By seeing how our sense of self is constructed, how our quest to enhance self-esteem makes us miserable, and how we’re part of a larger whole anyway, we become less concerned with egoistic aims and feel more connected with others.

It’s Really Not Personal

Virtually every school of psychotherapy helps clients identify or “own” their feelings. Most therapists hold authenticity, genuineness, and being true to oneself among our highest aspirations. But when we glimpse anatta, these aspirations start to lose their importance. In fact, we discover that there are distinct advantages to not owning any feelings as ours.

As mindfulness practice deepens, we see emotions in greater and greater refinement. Rather than being vitally important, meaningful aspects of ourselves, with names like love, anger, fear, or longing, increasingly look like patterns of bodily sensations, perhaps along with visual images, accompanied, like everything else, by the mind’s persistent narrative. It’s said in Buddhist traditions that with enough practice, we can observe mind-moments. These are the briefest experiences of which a person can be conscious. Traditionally, a mind-moment is defined as 1/10,000 of the time it takes a bubble to burst. At this level of refinement, seemingly solid events like “my anger,” “my lust,” “my sadness,” and “my joy” are revealed to be more like a movie, actually made up of many separate frames strung together, producing the illusion of continuity.

Let’s say a friend to whom I’ve been extraordinarily generous treats me badly. In an ordinary state of mind, with a coherent and well-developed sense of self, I’d think, “I can’t believe he did that to me after all I’ve done for him.” And with each repetition of that thought, I’d feel more anger and review more reasons why he’s bad and I’m good.

If, in contrast, I’ve cultivated enough mindfulness to glimpse anatta, I might simply notice my back and neck muscles tensing, my heart and respiration rate increasing, and images of decapitating my former friend dancing across the screen of awareness. It’ll all unfold as an impersonal process—waves of psychophysiological arousal accompanied by images and subvocal words. Experienced in this way, as impersonal bodily events, emotions are easier to manage. Also, they don’t get reinforced continually by ruminative thoughts, so they tend to pass more quickly.

But what about “owning” feelings, and being “genuine”? Isn’t this an important part of psychological health? Indeed, if a fellow walks into my office and says, “You know the way your friend can piss you off sometimes?” or, even more removed, “Doc, I know this guy who has trouble performing in bed,” there’s certainly merit to helping him eventually say, “I feel angry at my friend” or “I’ve been having trouble maintaining an erection.” However, insight into anatta suggests an additional, more advanced therapeutic step that isn’t usually part of treatment. We can help our clients observe emotions—or all phenomena, for that matter—as events arising in consciousness, impersonal processes resulting from factors and forces, not experiences “owned” by anybody.

In the context of anatta, we can tolerate a broader range of feelings with greater intensity than from our habitual framework of “selfing.” Having practiced being with, rather than fixing itches, aches, and pains in meditation practice, we develop the capacity to tolerate, or even embrace, the bodily sensations of strong emotions. Experiencing them as simply states of somatic arousal drains them of their personal, narrative meaning. We then no longer feel compelled to do something about them. Rather, we can feel them arise and pass, like other contents of the body-mind.

Of course, this attitude has potential pitfalls. In relationships, identifying and communicating the emotions that arise in response to one another are an important part of intimacy. Posturing as though we’re experiencing our emotions with awareness of anatta when we can’t actually do it experientially becomes just another defensive, intellectualized stance. Our underlying identification with the emotion will no doubt manifest in some other way, as our hurt, anger, or fear finds expression. In contrast, connecting with feeling while genuinely seeing its impersonal nature can allow for deep intimacy. We can share our experience with another person fluidly and openly, with less of the shame, righteousness, fear, or clinging than we might otherwise experience if we were identifying with or “owning” the emotion.

Take, for example, an interaction in couples therapy after a guy had “helped” his wife with a computer problem using a tone of voice that was clearly intended to make her feel stupid about technical challenges. A typical “selfing” response by his wife might be “I can’t believe you’re being such a jerk. You never talk to the kids like that when they ask for your help.” But with a bit more mindfulness—and less self—the feedback sounds different: “I’m trying not to fall into our typical pattern here. When you speak to me like I’m a dumb kid, I get flooded with feelings of being small, stupid, and inadequate. Then anger comes up with the thought that I don’t deserve this. Then I just want to get away from you. Is this what you want? I don’t think it is. And I certainly don’t like it.”

If the husband were also able to be especially mindful, he might say, “I’m sorry. I’m anxious about finishing my presentation for tomorrow, so I guess I reacted to your question like it was an imposition. And maybe because I’m kinda freaked out about how I’ll do, I sort of tried to boost myself up by putting you down. I know it’s a bad strategy.”

Nobody to Protect or Defend

What would a day be like for you, or your clients, if you weren’t preoccupied with yourself? What would you wear? What would you do? How would you spend your time? Many of the concerns that occupy our waking (and sleeping) moments would lose their potency.

Most of my thoughts and behaviors are designed to increase my pleasant states of mind and decrease my unpleasant ones. As a husband, parent, son, brother, friend, therapist, and colleague, this includes wanting to increase pleasant states of mind and decrease unpleasant ones for a lot of other people as well. Truth be told, however, a lot of my motivation to help those I love and work with comes from either wanting to feel that I’m a good person (buttressing my ever unstable self-esteem) or wanting to avoid feeling the pain that arises when I empathically resonate with another’s suffering. In other words, even when I’m being a good guy, an awful lot of concern with “me” is fueling the process.

A radical implication of grasping anatta is that we no longer devote our energies so relentlessly to enhancing pleasure and avoiding pain. How weird is that? In the rare moments when I taste this, my motivation shifts from scheming and strategizing about how to feel as good as possible to opening to whatever may be happening in the moment. This doesn’t mean purposely choosing pain or denying pleasure, but rather being with pain without trying to fix it, favoring being awake over being comfortable. Surprisingly, this shift can be a tremendous relief. It’s as if the mind—worn and weary from endlessly wishing things would be other than they are—gets to rest in accepting what is. And when I notice how much of what I stress about all day involves trying to bolster my self-esteem or hold onto pleasure and avoid discomfort, the struggle gives way to an inner chuckle about my insanity.

This awareness of the price we pay for self-preoccupation comes most readily when we can see the thought-stream for what it is and not identify so much with the contents of our minds. Combined with seeing that our emotions are just a mix of bodily sensations, words, and images, this realization can lead to surprising fearlessness, even in the face of major life challenges.

A friend of mine demonstrated the power of glimpsing anatta one day in a restaurant. Laurie was a woman in her late 50’s who’d been divorced for many years. Then she met George, fell in love, and got married. About a year and a half later, he developed a fast-moving cancer and died after a rapid decline. Laurie was heartbroken. As someone who’d engaged in both psychotherapy and meditation practice for a long time, she was in touch with feelings and had little difficulty connecting with her sadness, frustration, and anger.

Because we live on opposite coasts, I hadn’t seen Laurie for several months after George had died. When we finally got together she said, “You know, I hesitate to tell some people this, but sometimes I’m really okay. For example, right now as I look at you, I’m aware of seeing you in my visual field, hearing your voice, and feeling connected with you, as well as noticing the sights, sounds, and smells of the restaurant. As I talk about George, I feel sensations of sadness arise and see images of him. But I have a deep awareness that if he hadn’t gotten sick, the only real difference would be that instead of sitting here in the restaurant with you and having the thought George is dead, I’d be having the thought George is home in California. It’s really just a thought and these sensations of sadness that are different. Consciousness is still unfolding as a series of moments, and either way I’d still be here experiencing you and the restaurant.”

Along similar lines, my 80-year-old client Donna has been meditating regularly for the past few years. Her eldest son is addicted to alcohol, narcotics, and spending money. For years, Donna was tormented by doubt. Where did I go wrong? Was I too indulgent? Should I have sought help for him as a boy? Have I been a bad mother? Am I enabling him? Am I abandoning him?

Through mindfulness practice, the whole drama has become less personal. “I know it sounds weird,” she told me, “but I no longer think of his behavior as a reflection on ‘me.’ Of course, I want the best for my son, but most of what happens is beyond my control. I did what I did, given who I was at the time, and I’m doing the best I can now. My life really is just a series of moments.”

When we relate to each moment as the impersonal unfolding of changing experience in the field of awareness, rather than “my joy” or “my sorrow,” we can face more adversity with less resistance. There really is nothing to fear, because all that might arise is another moment of comfort or discomfort, pleasure or pain, in the present. In fact, my wife, Gina Arons, has recently been experimenting in her clinical practice with a simple technique that came to her as an insight during a Watsu bodywork session. It reliably helps awaken the freedom that comes from recognizing anatta. All you have to do is embrace your insignificance. Every time a thought about being respected or disrespected, liked or disliked, valuable or worthless, special or ordinary enters the mind, just think, It’s only my desire to be significant that’s causing suffering again. If I can embrace my insignificance, it’s all okay.

Consider it this way: do you know who the King of England was in 1412? I don’t either, but in 1412 a lot of people knew. What’s to become of all of our achievements and failures? Even if some people remember us for a little while, in a few hundred million years, the earth will be too hot for humans, and we’ll all be gone. Not to mention the fact that there are 100 thousand million stars in the Milky Way alone, which in turn is only one of about the same number of galaxies in the universe. So as one of seven billion people alive here today, on one tiny planet in a vast universe, we really are pretty darn insignificant. Contemplating this each time our narcissism becomes problematic can help us relax our instinct to buttress, defend, and protect our “self.”

One of my wife’s clients lost a high-powered job following a corporate buyout. After enjoying some time off, he reentered the job market only to become depressed when he had to settle for a lower-status position. Exploring his feelings in therapy, he realized how attached he’d become to feeling that he was important: in his old job, everyone needed to consult him, and he made all the big decisions. Now he was engaging his talents again, but was no longer the star of the show.

My wife introduced the notion of embracing insignificance. At first he was put off; it seemed like an emasculating prospect. But as he began to experiment with the idea, he started to engage more with his friends and family, finding meaning in ordinary activities, like playing the piano and gardening. When he embraced his insignificance, he found he could enjoy the present moment without so much judgment or fear. He also noticed that he felt less stressed and became curious about how he’d gotten so addicted to being a star.

Liberating as these insights can be, our minds are quite agile at constructing defenses, and intellectual understandings of anatta without deeper awakening readily open the door to spiritual bypasses. Most of us would love to leapfrog over longing, grief, and fear to arrive at equanimity. But if we’re aware that we need first to be open to and process the painful emotions that come with disappointment, loss, or injury, we can look for paths by which we, as well as our clients, might taste the liberation that comes from awareness that it’s all a passing show. Mindfulness practice, by cultivating awareness of present experience with acceptance, increases our capacity to ride the waves of pleasure and pain.

Copernican Therapy

As we come to see the reality of anatta and experience the relief and freedom that this realization brings, our orientation toward treatment may shift. Perhaps it’s now time for us to follow the lead of the Buddha and other wisdom traditions and engage in a Copernican revolution of psychology, allowing egocentrism to fall by the wayside as we come to see that it’s not only illusory, but remarkably painful and constraining.

If we take the our field’s current enthusiasm for mindfulness to its natural conclusion, we’ll come to see directly how our hardwiring to enhance self-esteem, pursue pleasure and avoid pain, and identify with our thoughts and feelings as real and personal causes endless, unnecessary suffering. As the 20th-century Taoist philosopher Wei Wu Wei said, “Why are you unhappy? Because 99.9 percent of everything you think, and everything you do, is for your self. And there isn’t one.”

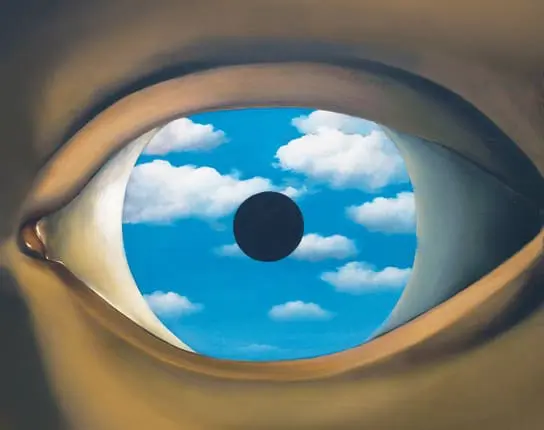

Illustration © Superstock / Magritte

Ronald Siegel

Ronald D. Siegel, PsyD, assistant professor of psychology, part-time, at Harvard Medical School, teaches internationally about the integration of mindfulness and compassion practices, as well as psychedelics, into psychotherapy. His most recent book is The Extraordinary Gift of Being Ordinary: Finding Happiness Right Where You Are. Learn more at DrRonSiegel.com.