Theresa, a 37-year-old African-American civil-rights lawyer, tells me in our first session together that she’s been miserable for a month. During that time, she’s lost weight she can ill afford to lose, and has been sleeping only four to five hours a night. Alternately listless and agitated, she’s been unable to concentrate at work. She leaves her office late, feeling guilty for what she hasn’t done, anxious that she’ll have to make up for it the next day. She used to go dancing with friends in the evenings, but now she tells them she’s tired. At home, she watches TV and eats frozen dinners. Sometimes, she measures her wine in bottles, not glasses. She’s feeling increasingly hopeless. She’s clearly clinically depressed, and her internist and psychotherapist have urged her to take antidepressants, but she doesn’t want to. She’s come to me to find a better way.

Theresa knows I view depression differently from how her doctor and therapist do. “Depression isn’t a disease,” I explained to her on the phone when she called to make an appointment. “It’s not the end point of a pathological process. It’s a sign that our lives are out of balance—that we’re stuck. It’s a wakeup call, potentially the start of a journey that can help us become whole and happy, a journey that can change and transform our lives.” Before any patients visit my office or pay me a fee, I speak on the phone with them, letting them know who I am, what my perspective is, and how I work, and make sure they want to participate in what I have to offer. I usually suggest that before the first appointment, they read something I’ve written about my practice, to get to know more about the meditative, eclectic, active, and engaged “Unstuck” approach I’ll offer.

The fit between what I’m offering and what my patient is hoping for will be the springboard for all our work. It’ll provide the shared vision on which we can draw in the difficulties and challenges that may come in any therapy. Commitment to an integrative approach—and the urgency that may fuel that commitment—help provide the energy that sustains us in meeting the challenges of our work together.

I begin, as any therapist would, by asking Theresa what happened a month ago, right before her depression. She says she’d just ended a relationship, and she tells me that at almost 40, she still doesn’t have a man who loves her, and she still doesn’t have a child. I listen carefully as she describes the inhibition and despondency that shadowed her childhood; the recent breakup with her boyfriend has plunged her into the same kind of hopeless darkness she remembers from that time. A thousand miles away, she tells me, her mother’s arthritis has slowed her to irritated immobility, and her father’s sight and vigor are fading. Theresa feels she should be with them, but she doesn’t want to, and feels guilty about that. “I carry my whole organization on my back, too” she says ruefully, “women’s rights for everybody except this woman.”

As I take in what Theresa is telling me, I encourage her to see herself as a student and adventurer, an active participant in our work together. Indeed, she’s the one primarily responsible, with my guidance, for helping herself. “Self-care,” I often tell clients, “is the true primary care.” From our first session, I convey to her my belief that she has within her the resources for her own healing. I begin to help her recognize what she’s already doing that’s helpful to her. In her case, the morning yoga she still sometimes does gives her energy; and phone calls or visits with her best friend, Barbara, dispel, at least for a while, her loneliness. I write these activities down on a prescription pad, as another physician might an antidepressant drug, crafting “a Prescription for Self-Care” at the end of the first session.

I teach Theresa (and virtually all of my patients) a simple meditation technique called “Soft Belly,” involving slow deep breathing in through the nose, out through the mouth, with the belly soft and relaxed. I encourage Theresa to close her eyes as she breathes so as to remove distracting stimuli. I suggest that she say to herself, “soft” as she breathes in through her nose and “belly” as she breathes out through her mouth. If thoughts come, I say, let them come, and let them go.

“Soft belly” is, I explain, an antidote to the fight-or-flight and stress responses, which figure prominently in the development and deepening of depression. Soft belly brings more oxygen to the lungs and stimulates the vagus nerve, which is central to relaxation. Slowly, I tell Theresa, the relaxation of the belly will spread to the other muscle groups also.

I explain to Theresa that though the research studies are most often done on 30 to 40 minutes a day of meditation, just a few minutes several times a day will help balance her physiologically, slow her anxious, pressured thought patterns, and give her a better perspective on her life. Equally important, as she sees she has the capacity to help herself, she’ll be overcoming the helplessness and hopelessness that are hallmarks of depression. I add “Soft Belly 3–5 minutes, 3–5 times a day” to Theresa’s Prescription for Self-Care.

I do soft belly along with Theresa and with all my patients. It’s of course helpful for me to be as relaxed and open as possible in my sessions. It conveys an important message to my patients: “We’re on this journey together. I’m not an observer. I’m here with you, learning as well as teaching, experiencing life, and dealing with my own stress along with you.” Dealing with depression and its challenges, and with stress, generally, is, I’m recognizing and admitting, not separate from our lives, an extraordinary response to a pathological situation, but an ordinary and ongoing part of them.

We speak in the weeks ahead about the historical context of Theresa’s depression: her mother’s coldness; her isolation as a young black girl in a still-segregated, white southern community; her tendency to take responsibility for the emotional lives of others—her parents first, and then her employees and lovers. Still, I’m continually bringing our focus back to what’s happening right now—how present feelings reflect past disappointments, and how she can relax with, learn from, and move through them. If she were to ask, I’d explain that this is a meditative, present-oriented approach to psychotherapy.

Theresa, significantly more relaxed as well as reassured after our first session, felt encouraged and supported by the Prescription for Self-Care. Each week, I ask her about her progress, and I express appreciation for what she’s doing well, while not being dismayed by what has been too difficult, or what she’s ignored or neglected. Our work isn’t about her “good” or “poor” compliance (what an ugly, condescending word!), but about what she can learn from difficulties, avoidance, and defeats, as well as from “success.”

Sometimes, patients who seem originally committed to this Unstuck approach grow discouraged and are reluctant to pursue it. Nagging doubts remain about whether antidepressants might be the best and easiest answer, after all, or at least a necessary precondition for improvement and therapy. I respond with information on the most recent metanalyses of drug research, which show that when unpublished negative studies are included along with positive, published ones, drugs are little better, if any, than placebos. I tell patients that I’m not “against” the drugs: I just see them, with their uncertain benefits, significant side effects, and potential for habituation, as a last resort, not a first choice.

Like many depressed people, expecting to get a prescription but not much more in the way of attention, Theresa is afraid of being “left alone” with her depression. I assure her that I myself have been on the journey through and beyond depression, and that I’ll be there with her at every step of her journey. I make sure she understands we’ll have regular appointments—a usual feature of psychotherapy, but a major departure for people who are used to seldom seen, drug-prescribing physicians. I tell my patients they can call me anytime, and find that this reassurance is itself powerful medicine: even though patients know they can call me, that I’m always there, almost no one does.

In our first or second session, I directly address the comprehensive biological dimensions of depression. “Depression isn’t a disease,” I say, “but diseases of various kinds, and imbalances in biochemistry and nutrition, can cause or contribute to it.” I make sure my patients see a competent primary care physician who can rule out the obvious physical causes of depression: reactions to medication, and conditions like cancer, diabetes, heart disease, multiple sclerosis, and so on.

If there are no obvious physical causes, I encourage my depressed patient to find a physician who can look for and treat a variety of conditions less commonly diagnosed, which may be implicated in depression, anxiety, and chronic fatigue. These include nutrient deficiencies, food sensitivities, subclinical hypothyroidism, heavy-metal toxicity, and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. I sometimes test for these myself. More often, I refer to other physicians who practice “integrative” or “functional” medicine.

Unless you’re a physician or trained nutritionist, you shouldn’t “prescribe” complex dietary changes. Nonetheless, you can certainly suggest basic guidelines for healthier eating. I always encourage patients to eat whole foods (preferably organic), little or no processed food, less sugar, protein primarily from vegetarian or fish sources, poultry rather than red meat, and increased doses of fiber. (We consume about one tenth as much as our Palaeolithic ancestors and our indigenous brothers and sisters.) Because our food supply is so depleted, and given the ordinary stress of living in modern society, virtually anyone can benefit from a high-dose multivitamin and multimineral supplement (without iron, unless anemia is present). People suffering from depression or bipolar disorder will benefit from supplementation with omega 3 fish oil, 2-6 grams a day. Those with gastrointestinal as well as emotional upset may well find relief from both kinds of symptoms by taking supplements with “probiotic” bacteria (Bifidus and Lactobacillus) that normally live in a healthy gut.

Exercise is critical for mood regulation. In fact, next to speaking with an experienced, reliable, and compassionate listener, exercise is probably the most effective of all the antidepressants. As a therapist, you can provide information about the benefits of exercise from a wealth of studies in peer-reviewed journals and help your patients develop individualized exercise programs. The effectiveness of jogging is well-researched, but if your patient hates doing it, it won’t happen. Walking, running, dancing, and yoga have been demonstrated to be enormously helpful. Theresa was already doing yoga, and I encouraged her to continue. Later, I suggested that each morning she put on fast music and dance for 15 minutes.

From the first session on, I give my patients detailed instruction in guided imagery, focusing most often on two images: the creation of a “safe place” where they can find calming sanctuary in difficult, stressful times; and consultation with an “inner” or “wise” guide—an emblem of their intuition and imagination, on which they can call for advice and counsel. I often teach “Dialogue with a Symptom, Problem, or Issue (SPI),” a Gestalt-like exercise, in which a rapid, written dialogue between my patient and her physical, emotional, spiritual, social, or interpersonal SPI often reveals both its origins and possible solutions. I work, too, with journaling, drawing, and movement to express and reveal feelings and release them. The message to my patients is clear and consistent: you can mobilize your own mind and body to help and heal yourself; I’m here to help, to equip you to do it, and to support you as you do.

There may come times, especially when working with seriously depressed people, when the increased hopefulness and good feelings you’ve helped stimulate seem to dissolve. Often, I find that this is a good time to ask my patient to consult her “wise guide,” or to use the dialogue with the SPI to mobilize her capacity for healing. Sometimes, I use expressive techniques—fast deep breathing, pounding pillows, and holding yoga postures at length—to bring up suppressed feelings, facilitate emotional release, break up physical rigidity, and mobilize energy.

Occasionally, someone’s distress is so great that she insists on what one of my patients called “a physiological boost,” something beyond the holistic approaches already tried. At this point, I may well use the natural “precursor” supplements that directly increase the levels of the neurotransmitters serotonin and norepinephrine, including S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) and tryptophan, and the herb St. John’s wort. While these can produce side effects similar to those of drugs, they’re usually far less severe. I don’t regard the use of these precursors as signs of treatment failure, but as necessary, quite often temporary, therapeutic aides.

Only when these supplements, together with the rest of my approach, don’t work, or if my patient explicitly requests it, do I refer her for pharmacological therapy, and I continue to work with her while she sees a

psychopharmacologist. Except when clients have debilitating chronic illnesses that may well become terminal, the time people in my practice spend on drugs is almost always relatively brief.

A spiritual perspective informs my work from my first moments with each person. Not an explicit religious orientation, this perspective encompasses an appreciation for the yet unrevealed potential of each person, a sense of sacred connection within each of us to something larger than ourselves, and moments of inexplicable grace, which can transform each person’s work with me and on their own.

Not long ago on a phone call, Theresa reminded me of this dimension of her life and of our work together. She’d moved through her depression in two months of weekly sessions with me, without neurotransmitter precursors or drugs. She’d continued to see me once every month or two for “refresher sessions” for another three years. Then, two years ago, she moved away to take a position at a law school. I’d watched her grow over the years into a peacefulness that she’d never before known—meditating regularly, doing yoga, taking time for herself. Now we were catching up, and she was looking back on our work together.

“My depression and the sad state of my spiritual life were two sides of the same coin,” Theresa reflected. “First, I needed to look at myself psychologically, to see that I was depressed, and that mine were ordinary human problems. I wasn’t this bad, immoral woman, sleeping with guys who didn’t love me, drinking too much, and smoking pot. I just needed to see how what I did, and the sad, confused way I felt, connected to my childhood—to that lonely little girl with her desperate desire to please. And I needed to get my life on a track that worked for me. But I also needed to feel my spiritual side, and by that I mean the heart, or the soul, or the divine in me.”

Through her work with me, as well as meditation, yoga, and dance, Theresa said, she began to develop “some emotional radar to sense what I was feeling—whether anxious, sad, angry—to know if something was off-kilter. I learned that I didn’t need to fight it, that it was okay just to let myself feel the pain. It was just passing feelings, and not something fundamentally wrong with me. I no longer have the feeling that I won’t get what I want. I have what I want.” Here, she emphasizes that wonderful, present-tense word, so different from all the past-tense terms of loss and longing that marked her depression, “I feel whole and happy as I am. If I find a ‘significant other,’ that would just add to it.”

I thank Theresa out loud, and silently, too, for sharing with me what’s possible. Freud wrote about replacing neurotic with ordinary unhappiness. Psychopharmacologists praise the restoration of the “premorbid personality.” Theresa is showing me, telling us, what it means to move from being terribly, chronically, depressed to feeling blessed every day.

Case Commentary

By David Waters

Seldom have I been so split in my response to a case. On the positive side, I was impressed with how James Gordon brings out the healing potential within his patient, guiding her gently and supportively toward a new sense of self. What patient wouldn’t appreciate the kindness and generosity, the plethora of helpful ideas, the almost unlimited availability? I imagine many readers wish he were their therapist or are resolving to be kinder, more available, more spiritual healers themselves.

That said, I’m going to voice the more skeptical part of my reaction. Maybe it’s just a rainy day, maybe it’s reading the case three or four times as a reviewer, maybe it’s wishing that I could be that nice a therapist, but there’s something about this case that left me uncomfortable. After 37 years of teaching family doctors to take a mind-body approach, I have reservations about Gordon’s approach.

Again and again as I was reading this case, I found myself asking “What exactly is the therapy here?” The hallmark of this case is that Gordon seems to give Theresa almost unlimited access to himself in many different ways: availability by phone, reading materials, sharing his thinking and theory, offering intense personal connection and support in many forms. In addition, he gives her access to a vast range of healing modalities: psychotherapy, meditation, exercise, mantras, self-care teachings, overt emotional support, “a spiritual perspective,” herbs and maybe drugs, posthypnotic suggestion, diet changes, drawing, journaling, movement, guided imagery. The list is remarkably lengthy—but when you offer every therapy imaginable, the effective components of the approach get blurrier and blurrier.

Let’s not ignore the crucial fact that it seems to work: Theresa feels better immediately, seems to continue to feel better over time, and returns years later for a grateful check-in. She has clearly learned a central lesson of therapy: there’s nothing wrong with me; it’s how I use what I have that matters. What’s not to admire about that kind of approach? From my perspective, it’s so unfocused and overinclusive that I can’t tell what exactly is helpful and what’s therapeutic overkill. In light of all the debate surrounding healthcare reform and the prevalence of excess procedures in the healthcare system, I kept wondering whether such an extensive intervention was the best use of Gordon’s time and input. (I also kept wondering how many patients this man sees.) It’s the equivalent of a doctor who’s treating my multiple vague symptoms giving me 8 or 10 medications in a couple of visits, based on the theory that “one or more of these will probably help; I just don’t know which one.” I’d be glad to feel better, but next time I’d want to go to a doctor who focused more and could tell me more clearly what he was treating. For me, bringing clarity to the pain the person feels is an important function of therapy.

From my experience as a therapeutic supervisor, I kept noticing that most of the energy in this case seems to come from Gordon, and not much from Theresa. With his gusto and intensively supportive style, and his eagerness to keep offering treatment options, he seems to see providing the oomph for treatment as almost exclusively his responsibility. Frankly, I think I’d have a hard time routinely providing that same energy to all my patients. While I can certainly admire the energy and the caring, I know that offering this kind of treatment hour after hour in practice is just not for me.

Author’s Response

This commentary by David Waters contains a curious blend of wistfulness and aggrieved professionalism that points to a central dilemma for many practitioners in the helping professions. Most of us feel a genuine commitment to doing the best we can for the people we serve, and our efforts are too often dimmed by the weariness and cynicism that come with working in settings or with attitudes that keep us from being as effective and as compassionate as we can. But contrary to what Waters suggests, working the way I do doesn’t make me weary. Just the opposite! What’s energizing for me is the spontaneous encounter with each person I work with. While in this case, written for therapists, I emphasized the techniques I prescribed for Theresa, in fact, it was she who did all the work. My contribution was to serve as a guide in, and catalyst to, her own creative and challenging personal work. The 3,000 clinicians who’ve already trained at my center report to me that working in this way—emphasizing teaching and prescribing along with listening, rather than interpreting and analyzing—is less taxing, more personally satisfying, and often more effective than more conventional forms of therapy and counseling.

Then there’s the issue of what Waters calls “therapeutic overkill.” He compares my approach to prescribing “8 or 10 medications” and has concerns about multiple interventions obscuring the “clarity” necessary to find the root of a patient’s problem and deal effectively with it. But I believe his objections are based on a misunderstanding of this approach. Every medication may have negative side effects, and combinations often promote harmful interactions, but the Unstuck approach brings together synergistic techniques and suggestions, which enhance one another’s effectiveness. The sense of hopefulness that may come from meditation or guided imagery may power the effort necessary for dietary change and increased exercise; these activities, in turn, may further decrease the stress that precipitates and prolongs depression and open receptivity to other techniques, like dancing and drawing, which nurture imagination and intuition and open up still more choices. Rather than therapeutic overkill, this is a way of working that’s simultaneously comprehensive, organized, and individualized.

I believe Waters’s concern about teasing out more specifically which of the techniques is working is largely an academic question. What people want is to feel better—to find hope in the midst of their suffering and learn new ways to heal themselves. Making multiple approaches available allows each person to create, with her therapist’s help, a comprehensive program, individualized to her needs and preferences. Endless questioning—in the name of intellectual precision—about which technique is “the one” has in my experience proved a barrier, not an aid, to understanding how best to address the physical and mental health problems that beset our country. It’s time to focus our intellectual efforts—and a significant portion of our research dollars—on the development and study of comprehensive approaches that are grounded in self-care. These—with an ongoing, compassionate, therapeutic presence—represent the best, most promising hope for the future of psychotherapy, and for our healthcare system.

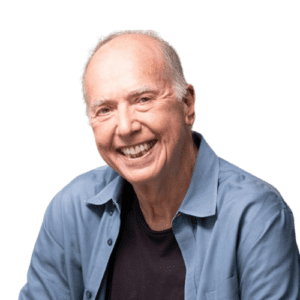

James Gordon

James S. Gordon, MD, is a psychiatrist, the founder and CEO of The Center for Mind-Body Medicine, and the author of Transforming Trauma: The Path to Hope and Healing. He is a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Family Medicine at Georgetown Medical School and chaired the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy. His work with war-traumatized children in Gaza and Israel, both of which he has visited 20 times, has been featured on 60 Minutes in 2015, as well as in The New York Times and The Washington Post.

David Waters

David Waters, PhD, is a psychologist in private practice in Charlottesville, Virginia. He was a professor of family medicine and psychiatry at the University of Virginia Medical School for 37 years. He retired in 2008.