Ever since the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, a series of shocking videos of police violence and lethal brutality against African Americans has sparked waves of protest in black communities across the country. But as so often happened in the past, the media too readily focused on lurid images of “black rioters” and “violent mobs” without providing much context for understanding the conditions of daily life that could possibly spark such explosive outrage. What was missing was the reality that, for all the undoubted progress we’ve made toward greater justice and fairness since the Civil Rights movement, racism is so woven into the fabric of our economic, social, and political institutions—into our common- place, albeit unconscious, attitudes—that it’s largely invisible to most white people.

Last summer, amid the tabloid media coverage of yet another series of eruptions of racial fury in Baltimore after the death of Freddie Gray, a book called Between the World and Me by journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates, who had himself grown up in Baltimore, drew wide attention for providing an extraordinarily penetrating look at the inner life of the young men living in communities that Ken Hardy, one of the authors in this issue, calls “wall-less prisons.” Coates describes the chronic fear and anxiety that so many black people experience— unprotected by the safety nets of good education, inherited wealth, safe neighborhoods, or a criminal justice system that wants to keep them safe from crime, as opposed to locking them up indiscriminately. Coates offers a glimpse of the ordinary lives of millions of African Americans, who aren’t privy to what he calls “the Dream”— more like a mass hallucination—that sustains white America in its sense of distance from the problems of racial inequality.

“Very few Americans,” Coates writes, “will directly proclaim that they are in favor of black people being left to the streets. But a very large number of Americans will do all they can to preserve the Dream. No one directly proclaimed that schools were designed to sanctify failure and destruction. But a great number of educators spoke of ‘personal responsibility’ in a country authored and sustained by a criminal irresponsibility. The point of this language of ‘intention’ and ‘personal responsibility’ is broad exoneration. Mistakes were made. Bodies were broken. People were enslaved. We meant well. We tried our best. ‘Good intention’ is a hall pass through history, a sleeping pill that ensures the Dream.”

Coates’s provocative book represents a challenge to all of white America, but especially to those of us who are white therapists and pride ourselves on our ability to understand the impact of social context on the deepest reaches of our emotional lives. This issue of the Networker is an attempt to explore what we can contribute as a profession to the “conversation about race,” which, as lame and ungainly as the phrase often sounds, keeps heating up around us, even as most of us have done our best to ignore it. The intent is not somehow to analyze racism as yet another clinical problem that we can solve through our good intentions, insight, and therapeutic ingenuity, but to recognize the hard and uncomfortable truth of how racist oppression, explicit or implicit, doesn’t just harm “them.” Ultimately, it harms us all.

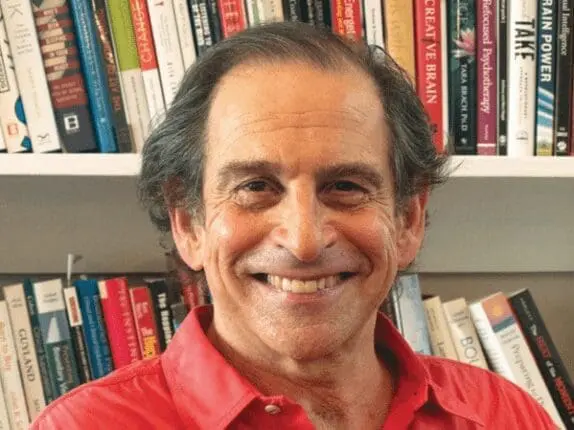

Rich Simon

Richard Simon, PhD, founded Psychotherapy Networker and served as the editor for more than 40 years. He received every major magazine industry honor, including the National Magazine Award. Rich passed away November 2020, and we honor his memory and contributions to the field every day.