Three decades ago, doing therapy was a relatively uncomplicated affair. After graduate school, you set up shop as a family therapist, a psychodynamic healer, or a cognitive-behavioral specialist. Whichever model you adopted, you were likely to see yourself as firmly in charge of the process, with your client (or “patient”) following your lead. You, after all, were the expert. Few clinicians felt the need to explain how therapy was going to proceed, or if, indeed, it would even work. “Trust me,” was the unspoken byword. Most clients had no choice but to do so.

It’s a different world now. Prospective clients have a staggering range of therapies to choose from, encompassing brain-based protocols, Eastern-inspired healing approaches, and dozens of “alphabet” therapies, from EMDR and IFS to ACT, EFT, DBT, and AEDP. For what it’s worth, Wikipedia lists more than 175 distinct kinds of psychotherapy. Therapists need to sell their favored therapeutic approach, sometimes hard. If you hear a muffled thumping sound, it may be Freud turning in his grave.

In a host of ways, psychotherapy today is not your grandfather’s therapy. One element hinges on the promise of personal transformation. In William Doherty’s memorable piece, we explore whether we need to drop the longstanding therapeutic goal of complete emotional makeover and focus on more modest and achievable aims. Are we shortchanging clients by dialing down our ambitions, or can small changes make a meaningful difference in a person’s life?

But there’s another kind of change happening in psychotherapy. As Lauren Dockett documents, clients themselves are now a different bunch. First, they’re simply scarcer—today, one-third fewer people are in therapy than was the case 20 years ago. Those who do come, especially young people, are demanding a less mysterious, more egalitarian relationship with their clinician—and if they don’t get it, they may simply “ghost” (a Millennial term for exiting a relationship with no explanation). To avert these early departures, some clinicians are taking a leap into the unknown by soliciting regular feedback from their clients—not polite murmurs of approval, but frank, forthright opinions about how therapy is really going, every single session. As Eugene Gendlin, the originator of Focusing, used to say to his workshop participants, “I want to hear from people who are having trouble. Give me trouble!” But are we really ready to engage with it?

Whatever approach we choose, every therapist knows that the bottom line for change is a trusting clinician–client relationship. Dafna Lender addresses this perennial issue in a new key, tuning into the subtle “microbehaviors”—including a therapist’s vocal intonation, tempo, and pitch—that most reliably elicit safety and openness.

Here at the Networker, we’re mostly excited about the potential of our changing therapeutic landscape, because our observations watching dedicated therapists at work has shown us again and again that under the right conditions, they can always become more attuned and effective—and more satisfied in their work. To say “change is never easy” is an understatement, but the defining characteristic of this field remains a strong sense of curiosity and service, which has always driven the therapeutic relationship and, more often than not, brings out the best in human nature.

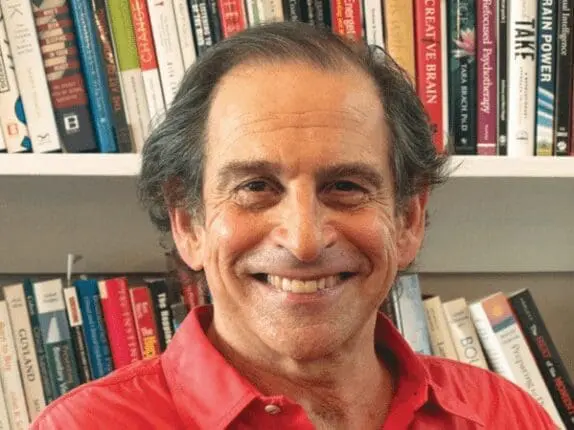

Richard Simon

EDITOR, Psychotherapy Networker

Rich Simon

Richard Simon, PhD, founded Psychotherapy Networker and served as the editor for more than 40 years. He received every major magazine industry honor, including the National Magazine Award. Rich passed away November 2020, and we honor his memory and contributions to the field every day.