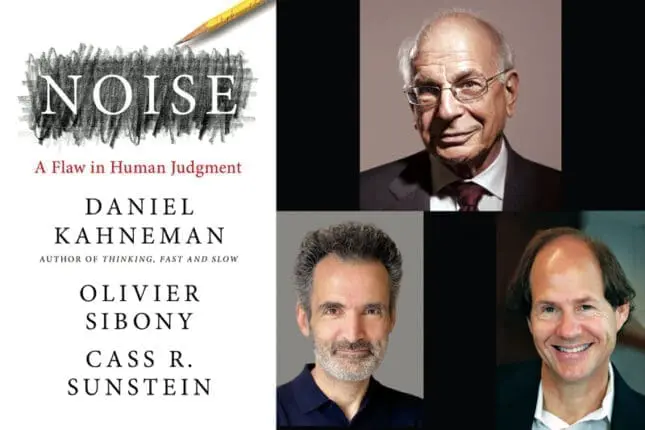

Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment

by Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass R. Sunstein

Little, Brown. 464 pages.

978-0316451406

In his brilliant magnum opus, Thinking, Fast and Slow, published in 2011, the behavioral psychologist and Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman presented a comprehensive picture of how and why our reasoning all too often and all too easily goes awry—and how we can begin to train our brains to do better (see my review in the Networker’s May/June 2012 issue). The title itself provided the key to the book’s basic principle: that our brains are ruled by two vital but competing thinking systems. One is fast and intuitive, propelled by our gut instincts, while the other is slow and deliberate, holding back on an immediate judgment to pause, consider, and reason through all the pluses and minuses of a given choice.

So strong is our intuitive thinking—and so much slower-on-the-uptick is our analytical thinking system—that reining in that trigger-happy, overly confident automatic thinking system is easier said than done. Fortunately, Kahneman peppered the extensive research on which he based his ideas with so many concrete, everyday examples that we could readily take away any number of practical tips for avoiding pitfalls in our own lives and therapy practices. Indeed, one of the book’s most remarkable aspects was the ease with which Kahneman translated an unwieldy and complex subject into an easily understood guided tour of the numerous psychological propensities and illusions that trip us up, as well as ways to manage our impulsivity and arrive at more reasoned—and reasonable—decisions.

No wonder I was eager to get hold of Kahneman’s new book, Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment, coauthored with Oxford University and HEC Paris professor Olivier Sibony and Harvard University professor Cass R. Sunstein! And no wonder I was disappointed when I started reading it, only to discover that it’s as stodgy and forbidding as Thinking, Fast and Slow is engaging and user-friendly! Nonetheless, amid the jargon-filled writing and the barrage of technical data are a number of important and useful perspectives for the psychotherapy field and beyond.

Noise lays out a problem that should give us all pause. Why is it, the authors ask, that two or more experts in a given field can look at identical case histories and data—and come up with broadly differing assessments and evaluations? This kind of inconsistency, they note, occurs across a broad swath of professional realms, raising questions of fairness, bias, trust, and credibility. The authors call this variability “noise.”

It’s a clever way to frame what happens when expert opinions diverge, but the word’s neutrality understates the potential costs of such inconsistency. In the therapy field, for instance, think of the possible consequences of variations in diagnoses, and the effectiveness and appropriateness—or not—of subsequent treatment. Medical evaluations can be equally chancy. The list goes on: child custody and foster-care placements can differ widely, depending on the case manager; the leniency or harshness of a jail sentence can hang on an individual judge’s perspective; a hiring decision can rest on a particular manager’s evaluation.

In all these ways, “noisy” decisions can be like a roll of the dice. When they fall in your favor, you win. Harsh or incorrect judgments may be not merely noisy but deafening, as they cascade into life-changing and potentially life-damaging after-effects. Worst of all, you can’t escape noise, the authors warn, because “Wherever there is judgment, there is noise—and more of it than you think.”

The authors are particularly effective in their analysis of noise in the criminal justice system. The success and difficulties in addressing disparities in legal judgments have implications for other professions—including psychiatry, psychotherapy, and other mental health disciplines—where faulty decisions can profoundly affect the course of human lives.

In 1973, Judge Marvin Frankel brought attention to the frequency with which the same crime carried vast sentencing disparities, making a court appearance seem like entering the lottery. Two examples: a man convicted of cashing a counterfeit check of $58.40 was sentenced to 15 years, while another man who cashed a counterfeit check of $35.20 received 30 days. Similarly, embezzlement convictions earned 117 days for one defendant but 20 years for another. A variety of studies found that a slew of random events—such as whether the local football team had won that weekend, or even the weather—could sway a judge’s mood and consequent decisions.

Outraged by the inequities, Judge Frankel called for “a detailed profile or checklist of factors that would include, wherever possible, some form of numerical or other objective grading,” and in 1984 Congress passed the Sentencing Reform Act to do just that. By the end of that decade, variations in sentence length declined sharply.

But many judges objected, claiming that mandatory rules left them little room to account for the complexity of a given case. In 2005, the Supreme Court struck them down, making them advisory only. Since then, the authors note, the legal system has produced “a disparity between the sentences of African American defendants and white people convicted of the same crimes.”

Somewhat similarly, inconsistencies abound in the fields of psychotherapy and psychiatry. The authors cite studies pointing out the presence of startling discrepancies in diagnoses, despite the guidelines set out in the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Because psychotherapists and psychiatrists alike must rely on the subjectivity of patients’ symptoms, especially in the absence of objective diagnostic tests, the authors acknowledge that the quest to find more uniformity is challenging. They call for more specific symptom descriptions, as well as the use of structured interviews with particular questions that can more accurately help screen for anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and other conditions.

These ideas are important and helpful, but they can lead to the paradox that left judges uneasy with mandatory sentencing rules. Making mental health diagnostic guidelines even more detailed and refined might reduce noise; then again, the individual, particular aspects of a given case might also make the practitioner feel hemmed in from the get-go, less free to use clinical experience and insight in assessing a patient’s troubles.

The challenges don’t end there. Even if a diagnosis is correct, professionals may still differ noisily about which type of treatments would work best—and that’s even before insurance companies weigh in with their own clamor about what types of regimens are covered and for how long. Then, of course, vast disparities in the presence, availability, and distribution of mental health resources occur throughout our country, with rural, minority, and low-income populations generally possessing less access. How do we tackle so many interconnected, competing, cacophonous systems, all going full blast at once?

With some difficulty! The sheer complexity of the “noise factor” would seem to limit the applicability of many of the authors’ noise-reducing solutions to such fields as business, finance, and marketing, which lend themselves more easily to data aggregation and statistical analysis, which, in turn, yield specific, measurable guidelines.

So where does that leave the subjective rest of us? Perhaps the bottom line is the authors’ acknowledgment, right up front in their subtitle, that noise is “a flaw in human judgment.” Each of us is unique, the authors write, which means that each of us possesses our own, distinctive “judgment personality.” At the same time, each case and each person being judged is also unique, needing to be evaluated on its own merits, as well as within general guidelines. Most of all, human judgment is naturally prone to the manifold flaws, fallacies, biases, and psychological illusions, as Kahneman describes in Thinking, Fast and Slow.

So perhaps it’s unsurprising that across all professions, only one cognitive skill set can decrease noise—a trait that the authors describe as being “actively open-minded.”

In other words: do your best to avoid getting caught up in fast, immediate judgments. Be willing to consider information and opinions that diverge from your own beliefs and go against what your lightning-fast intuition feels is right, based on nothing more than your gut. To reduce noise, take deep breaths and think slow—and find your way to the best decisions and diagnoses possible.

PHOTO © SUNSTEIN: PHIL FARNSWORTH

Diane Cole

Diane Cole is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges and writes for The Wall Street Journal and many other publications.